Review of Business Taxation

A Tax System RedesignedMore certain, equitable and durable

Report July 1999

SECTION 4 - CORE CONCEPTS AND PRINCIPLES

Determining taxable income using the cashflow/tax value approach

Recommendation 4.1 - Cashflow/tax value approach

|

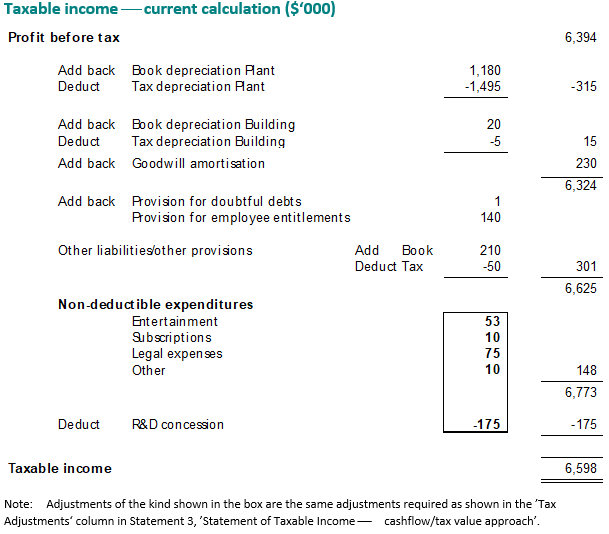

Calculation of taxable income

|

|

Incorporation in tax law

|

|

Revenue-neutral implementation unless expressly varied

|

Fundamental to the reforms of the business tax system recommended by the Review is a principle-based framework for a reformed income taxation system. The recommended framework is driven by the need to improve the structural integrity of the present system, to reduce complexity and uncertainty, to provide a basis for ongoing simplification and to align more closely taxation law with accounting principles wherever possible.

The need for a new approach

The existing law is based on legal concepts of income that have evolved over many years. Central to it are the concepts of ordinary income, statutory income including capital gains, and expenses and losses of either a 'revenue' or 'capital' nature.

As a consequence of the evolution of the existing law, assets may be taxed in a variety of ways depending on the purpose for which they are held. This creates uncertainty and complexity in the law, of the kind illustrated in the Review's first discussion paper, A Strong Foundation.

To distinguish expenses consumed in a tax year from expenses that essentially involve a conversion from one type of asset to another, the existing tax system uses the concept of capital expenditure. The absence of statutory principles guiding that differentiation has resulted in uncertainty and led to the mischaracterisation of some expenses.

Whether business expenditures are recognised for income tax purposes and, if recognised, the timing of their deductibility now depends more on the historical development of the law than on clearly enunciated principles. In particular, the treatment of the changing values of different categories of assets and liabilities has been grafted into the law in an uncoordinated and thus non-comprehensive way.

A range of expenditures - known as blackhole expenses by tax practitioners - either attract no deductions at all or are not deductible in a manner consistent with their declining value (see A Platform for Consultation, page 101). The lack of sound principles concerning the recognition of expenditure as well as assets and liabilities has influenced these outcomes - as has the ad hoc approach of adopting a multitude of amortisation regimes to recognise the decline in value of particular categories of assets. The lack of recognition, together with the mischaracterisation of some expenses, has led to distortions in the measurement of taxable income.

The Review is strongly of the view that a more coherent and durable legislative basis for determining taxable income is essential to reducing uncertainty and complexity in the present system. That redesigned tax law will underpin a more consistent, transparent and sustainable tax system. Having a structure which is more enduring and robust, and which can flexibly accommodate future changes, has much to commend it. Of itself, it will not imply a broadening of the tax base: variations to the base should occur only by express intention.

Features of the cashflow/tax value approach

Concept of taxable income

Determination of taxable income under the cashflow/tax value approach involves recognition of the two components of a taxpayer's income - the net annual cash flows from use of relevant assets and liabilities and the change in tax value of those assets and liabilities (see A Platform for Consultation, pages 27-34). Recognising the practical constraints in taxing the annual change in value of all assets and liabilities, the use of tax values ensures that taxpayers will generally continue not to be taxed on unrealised increases in balance sheet values.

Defining income in a manner structurally consistent with both economic and accounting approaches to income measurement - rather than relying on the current mix of statutory and judicial definitions of assessable income offset by an unstructured and highly differentiated set of deductions - supplies the high level unifying principle that cannot be found anywhere in the current income tax legislation. Application of that unifying principle will provide structural integrity and durability to the income tax law that the existing patchwork definitions simply cannot offer, however they might be amended.

Treatment of expenditure

An essential element of income measurement is the deduction of expenses consumed in the course of deriving gains. A treatment of expenditure which is consistent with the accounting approach of classifying expenditure by reference to the life of the benefit acquired is a fundamental feature of the cashflow/tax value approach.

All non-private expenditure, including existing blackhole expenses, will be recognised in the calculation of taxable income - unless specifically excluded by the law for policy reasons. The need to specify exclusions will result in greater certainty for taxpayers and administrators. As a general rule only individuals will be recognised as incurring private expenditure.

Where expenditure gives rise to an asset, and that asset is recognised for tax purposes at the end of a year, its tax value will be brought to account at that time unless specifically exempted. This is similar to the treatment of trading stock in the existing law. Under this approach, expenditure will be deductible over the period in which identifiable benefits are received from the expenditure.

Some transactions either will not be recognised or otherwise will be exempted from being treated as assets and liabilities (for example, most advertising expenditure). Some assets and liabilities will be exempted either because the compliance costs involved in valuation would not warrant their valuation or for specific policy reasons (Recommendations 4.2 and 4.3). Exemption of certain assets and liabilities from end of year tax valuation will also provide the mechanism in the law for the calculation of taxable income under the simplified tax system applying to taxpayers operating small businesses (see Recommendation 17.1) and for certain other taxpayers (Recommendations 4.4 and 4.5).

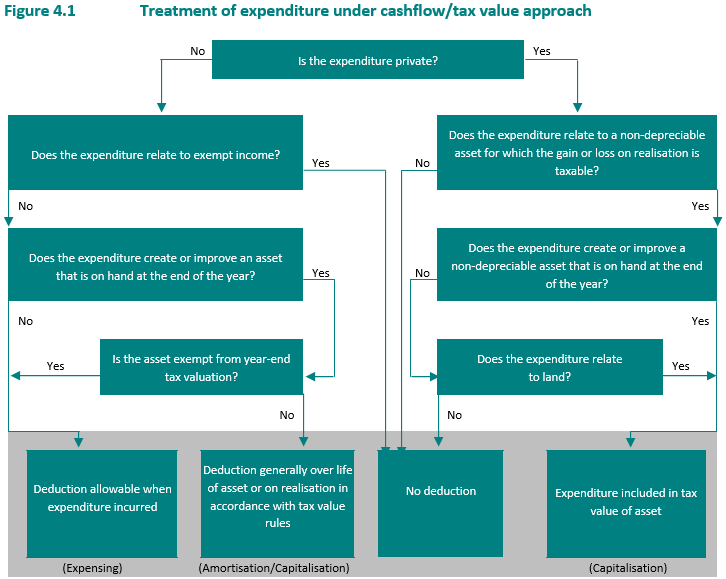

Figure 4.1 depicts the treatment of expenditure under the recommended framework.

Tax value of assets and liabilities

Critical features of the cashflow/tax value approach are the tax value rules for assets and liabilities and the meaning of 'asset' and 'liability'. As noted, the Review's recommended approach involves measurement of a taxpayer's income (or return on an investment) by taking into account changes in the tax value of assets and liabilities over a year.

The tax value of assets and liabilities on hand at the beginning and end of a year will be taken into account in the calculation of taxable income.

- •

- Increases in the tax value of assets and reductions in the tax value of liabilities will add to taxable income.

- •

- Decreases in the tax value of assets and increases in the tax value of liabilities will reduce taxable income.

Soundly based definitions of 'asset' and 'liability', and of their associated tax values in a range of circumstances, are required under this approach. A broad definition of an asset is required to protect the integrity of the tax base and to ensure that the tax law remains relevant in the face of asset innovation without the need for continual adjustment.

- •

- The meaning of 'asset' will draw on, and be generally consistent with, the accounting definition of an asset. There is no general definition of asset in the existing tax law. An asset is defined for capital gains tax purposes but this definition is more narrowly focused than the accounting definition. Consistent with the accounting definition, an asset will be something that embodies future economic benefits. Where an asset is held by a taxpayer, the tax value of the asset will generally be taken into account in the calculation of taxable income - unless it is excluded or exempt from year-end tax valuation.

- •

- The meaning of 'liability' will draw on the accounting definition of a liability. There is no definition of a liability in the existing tax law. In the new tax law, a liability will be an obligation that a taxpayer has incurred to provide future economic benefits. Consistent with the well understood meaning of 'incurred' in the existing law, there must be a present obligation to provide future benefits for there to be a liability. Some liabilities for accounting purposes, such as provisions for employee entitlements, will not be recognised as liabilities for taxation purposes, thereby effectively having a zero tax value (Recommendation 4.21). Where a liability is owed by a taxpayer, the tax value of the liability will generally be taken into account in calculating taxable income.

As noted earlier, some transactions will either not be recognised or will be specifically exempted from being treated as assets or liabilities often through the assignment of a zero tax value - whether for reasons of compliance cost or policy. In this regard, the Review emphasises (see Recommendation 4.1(c)) its intention that the cashflow/tax value approach be implemented in a revenue-neutral manner. Unless other recommendations in this report expressly propose variations to the existing law, the presumption should be that identifiable variations to existing policy will not be implemented by stealth. More generally, the benefits of a more robust and durable tax system should also be returned to taxpayers via lower tax rates.

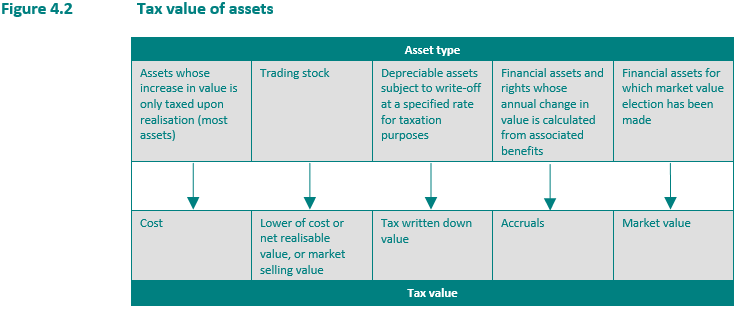

Figure 4.1 illustrates that the proposed tax value rules for assets will determine the timing of the deduction of expenditure in calculating taxable income. An outline of the tax value of most types of assets is depicted in Figure 4.2.

As can be seen in Figure 4.2, taxpayers will generally not be taxed on unrealised gains. Gains on most assets will continue to be taxed on a realisation basis. The main departures from this are the accruals treatment for some financial assets and rights (Recommendation 9.2) and the market value election available for financial assets (Recommendation 9.1) or trading stock (Recommendation 4.17).

Critical to the cashflow/tax value approach is the tax value concept. It enables practical recognition of asset and liability values in the measurement of the components of a taxpayer's income.

The Review recognises that the proposed approach will impose some transitional costs on taxpayers and their advisors as well as the Australian Taxation Office as a result of the introduction of new concepts and newly defined terms such as 'asset' and 'liability'. These transitional costs can be justified because of the greater simplification, certainty, transparency and durability of the recommended framework. The new approach to structure will produce long-term benefits for Australia's tax system, which the Review believes will far outweigh the shorter-term costs.

Most taxpayers operating small businesses will feel little practical impact from the new approach because of the Review's recommendations allowing them to opt into the simplified tax system (STS) described in Recommendation 17.1. Similarly, there will be little impact on individuals, who will continue to attract a cash basis treatment on most income and expenditure (Recommendation 4.4).

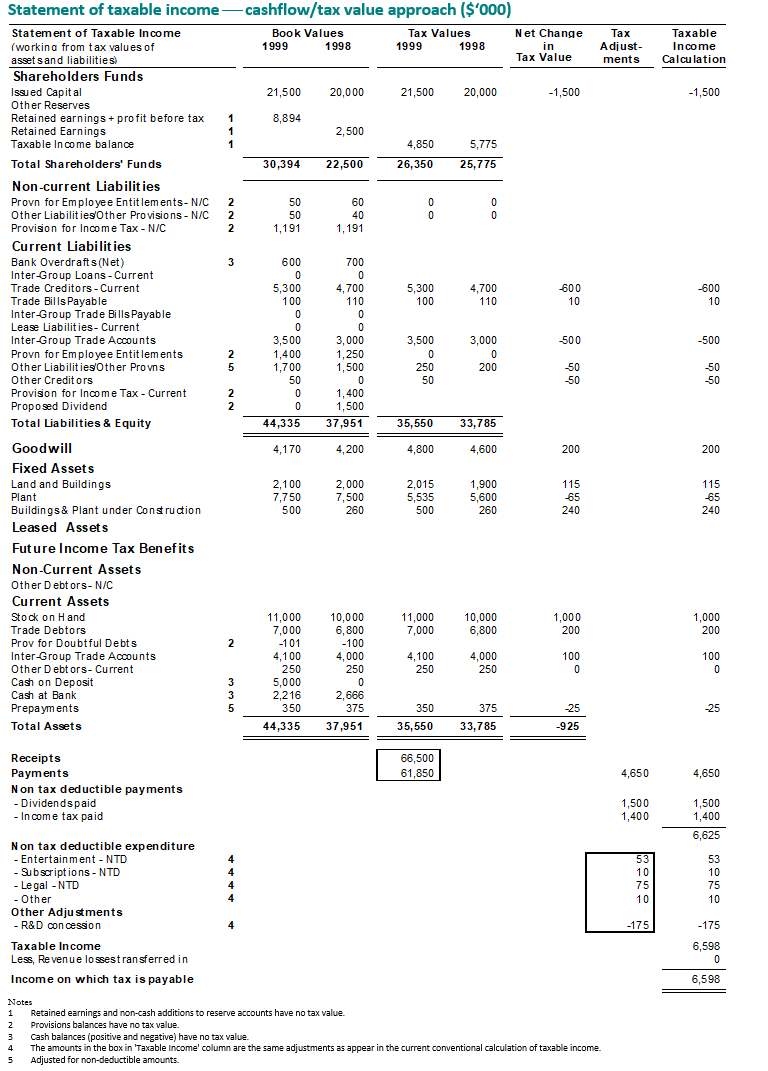

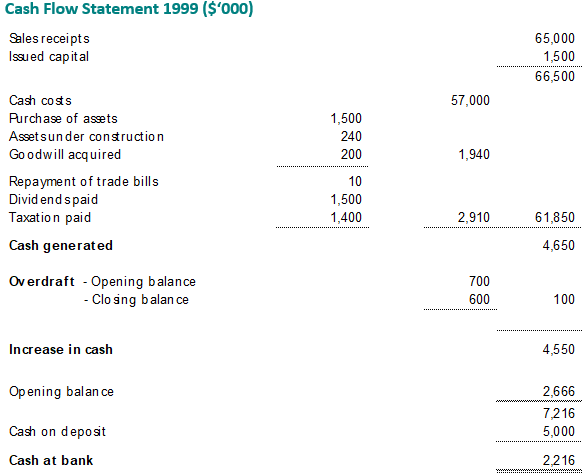

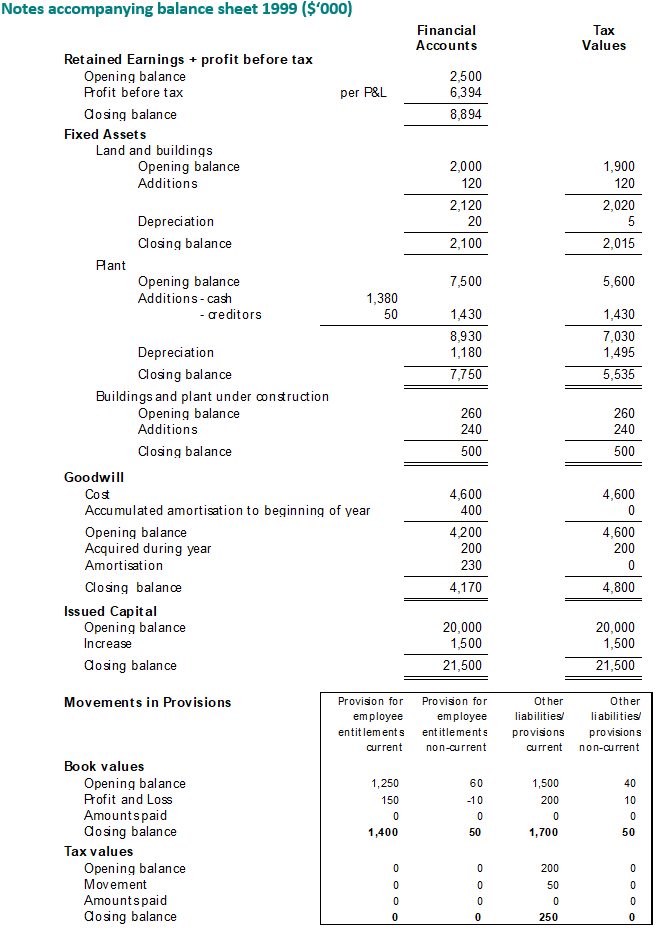

Calculation of taxable income

To determine a taxpayer's taxable income, adjustments will be required to the net income amount calculated under the recommended treatment of receipts, expenditure and changes in the tax values of assets and liabilities as explained above. These adjustments will be for specific policy reasons. For example, exempt income and the deduction for the extra 25 per cent of research and development expenditure will reduce taxable income. Examples of amounts which will increase taxable income, by requiring an addition to the net income amount, are non-deductible expenditures. These include payments of dividends and income tax, each of which will continue to be non-deductible.

Also, total spending initially having been taken into the calculation, expenditure relating to exempt income will be added back to increase taxable income by way of a specific adjustment.

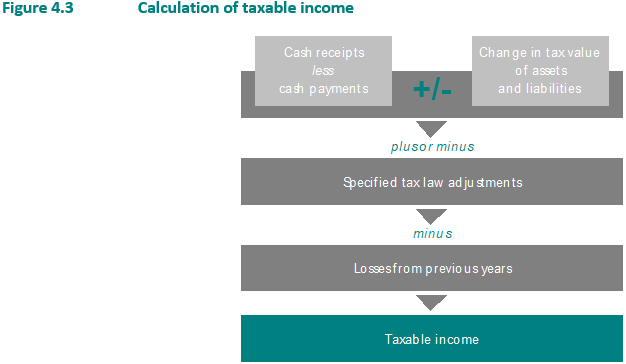

After taking into account these specific policy adjustments and the carry-forward of unused losses, taxable income will be determined as shown in Figure 4.3.

Under the existing system, the timing of deductibility of expenditure depends on whether the expenditure is of a capital nature. In accounting terms a capital expense is essentially a conversion from one asset (for example, cash) to another asset. In other words, expenditure is of a capital nature when it is used to acquire, create or improve an asset. The Review believes that reflecting this approach in the structure of the tax system will reduce uncertainty and remedy the mischaracterisation of some expenses in the present law.

A key objective of the cashflow/tax value approach is to classify expenditure as attracting immediate write-off, amortisation or capitalisation by reference to the life of the benefit acquired from the incurring of the expenditure. This is based on the notion of whether or not the expenditure gives rise to a recognisable asset on hand at year-end.

In A Platform for Consultation (pages 39-44), the Review discussed two options for determining taxable income under the framework incorporating changing tax values of assets and liabilities. One option maintains the existing assessable income and allowable deductions dichotomy. The other option adopts an approach based on cash flows and changing tax values of assets and liabilities. Both options are intended to, and would, produce the same outcome. They would also produce the same outcome that the current system is intended to do, under the same policy prescriptions.

The first option would involve the inclusion in assessable income of current receipts and earnings as well as the increase in the tax value of assets and the reduction in the tax value of liabilities. Deductions would include current expenditure as well as the reduction in the tax value of assets and the increase in the tax value of liabilities.

Some tax professionals seem to favour this option because it retains the existing concepts of assessable income and allowable deductions. However, as assessable income and expenditure include tax value changes for some assets and liabilities (for example, debtors and creditors), there would be a need for special rules under this option to remove the duplications. Removing duplication in the determination of assessable income and allowable deductions, however, underlines the equivalence between this option and the second option outlined in A Platform for Consultation.

It is this second option that the Review has concluded should be the approach to be taken in framing the legislation for the calculation of taxable income. It is based on cash flows (receipts less payments) and changing tax values of assets and liabilities. The Review does not see benefit in maintaining the existing terms of 'assessable income' and 'allowable deductions'. As noted, those terms would have significantly changed meanings if they were to be maintained in the new law.

As its primary advantage, this approach delivers structural integrity and durability of the resulting legislated framework. It is also consistent with the conceptual basis that has been developed for financial accounting. In addition, by minimising the number of specific rules required throughout the legislation (a problem that bedevils the current legislation), it will reduce the volume of tax legislation significantly as well as its complexity, thereby delivering lower compliance costs. The structural unification recommended will also provide a basis for ongoing simplification of the tax law.

Calculating taxable income will be conceptually consistent with accounting and economic approaches to income measurement - although, importantly, tax values will often be different, and less dependent on legal concepts, from values in the financial balance sheet because they will be derived from the treatment incorporated in the tax law. In particular, because realisation is adopted as the basis for taxing gains for most asset categories and because expenditures will usually be recognised when incurred rather than when provided for in accounts, tax values will differ from financial balance sheet values. For example, depreciable assets will be included at tax written down value and most provisions, such as employee entitlements, will have a nil tax value. As noted, including depreciable assets at tax written down values and most other assets and liabilities at cost ensures that related gains are only brought to account on realisation.

Impact of the cashflow/tax value approach

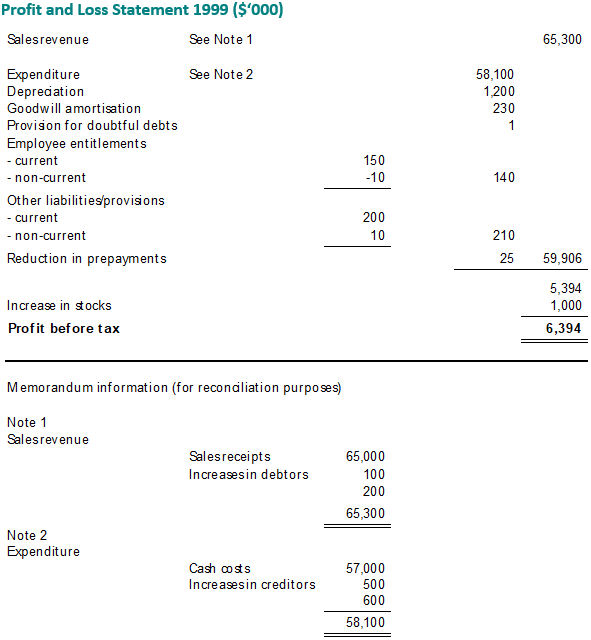

The recommended approach is not a revolutionary way of calculating taxable income that departs from all established processes. It does not result in radically different outcomes, such as bringing to tax unrealised gains. Substantively, the same calculations need to be made under the existing law and the proposed approach.

It has been suggested by some that changing from the current system of taxation to the recommended approach will add substantially to compliance costs and require major modifications to existing computer systems currently used to calculate taxable income. This is not the case.

Adoption of the cashflow/tax value approach will not, of itself, require taxpayers to change the way they currently calculate their taxable income and they can continue to use their current computer programs. Attachment A demonstrates how the approach can be applied in practice. Modifications to existing systems will, of course, be required to reflect policy changes resulting from the implementation of reform measures by the Parliament. This would be the case whichever legislative structure were to be adopted.

Assets and liabilities receiving a zero tax value

Recommendation 4.2 - Exemption principles for tax values

|

That classes of assets and liabilities not be recognised, or be exempted from the general requirement for year-end tax valuation (effectively receiving a zero tax value) if:

|

In Chapter 3 of A Platform for Consultation, the Review identified a range of business assets that taxpayers currently do not need to bring to account at year-end, even though their cost is generally immediately deductible. The range was not exhaustive. In the absence of specific exemptions, taxpayers would need to bring such assets to account under the cashflow/tax value approach for determining taxable income.

In principle, the year-end tax value of business assets and liabilities of taxpayers would be brought to account. Nevertheless, the Review considers that a balance needs to be struck between that principle and the compliance costs related to that recognition. There may also be particular policy reasons for not requiring certain assets and liabilities to be brought to account at year-end for tax purposes.

In selecting those assets and liabilities recommended for exemption, the Review has balanced the following factors:

- •

- the need to protect the integrity of the law - exceptions can create opportunities for manipulation and can lead to disputation about the precise meaning of the exception;

- •

- the cost to taxpayers of recording the tax value of assets - some assets can be difficult to value (for example, professional work in progress) and the inclusion of the tax values of some other assets and liabilities would have little or no impact on taxpayers' tax liabilities (for example, the net value of the assets and liabilities associated with a 20 year lease over property subject to regular commercial lease rentals); and

- •

- the degree of distortion (or impact on revenue) - some of the identified assets are usually realised within 12 months and so exemption under the current treatment is not particularly distortionary.

Simply exempting all short-term assets from being brought to account at year-end would not be appropriate. A rule as broad as that would cover assets such as trade debts and trading stock. Those assets often represent a significant portion of the assets of a business and excluding their value from the income tax base would be unacceptable. Accordingly, the Review has recommended general principles as well as specifying particular assets for exemption. Beyond the specific exemptions covered here, exclusions from asset/liability treatment are incorporated within a range of other recommendations - for example, in relation to 'routine' leases and rights (recognising, though, that a lease rental paid in one year for benefits in the next reflects an asset (prepayment) which would be brought to account in the first year and extinguished in the next).

Recommendation 4.3 - Specific exemptions producing zero tax values

|

That, consistent with the exemption principles, taxpayers not be required to determine tax values for the following types of assets at year-end:

|

Consumable stores and spare parts

Consumable stores and spare parts do not generally constitute trading stock under the existing law and so currently do not have to be valued at year-end.

The current treatment of consumables and spares is not entirely appropriate. Some taxpayers carry significant levels of such assets and deductions ought be allowed only as they are consumed. On the other hand, it would not be appropriate to require taxpayers to account for values below a certain limit.

A reasonable limit would seem to be $25,000. That will ensure that most businesses do not have to incur unnecessary compliance costs. Even where the $25,000 limit is exceeded, consumables and spares will not have to be separately accounted for if their cost has been absorbed in the tax value of other assets, such as in trading stock values.

Office supplies

Taxpayers currently do not have to account for the value of consumables and spares to be consumed, or used in machines, in a taxpayer's office. Usually, significant sums are not involved.

Requiring taxpayers to value annually stores of such relatively minor assets would impose additional compliance costs which cannot be justified in terms of tax law integrity or design. Accordingly, taxpayers will not be required to value these assets.

Standing crops and timber

Generally, taxpayers currently do not have to determine tax values for standing crops and timber established by them either for purposes of sale or, broadly, for environmental works on rural land. Establishment costs and development costs are deductible rather than added to the year-end tax value of these assets.

The current taxation treatment of short-term crops does not represent a significant distortion. The crops are harvested in the year following the incurring of the expenditures. Moreover, requiring their valuation for taxation purposes each year could be difficult, particularly for small farmers. The Review's principles would exempt these assets from year-end tax valuation.

Considerably more distortionary, however, is the current treatment of the costs of establishing and developing standing timber - because immediate deductions are granted even though a long-term appreciating asset is created as a result. In principle, the cost of establishing and developing plantation timber should be capitalised until the plantation is harvested.

Although that would be the outcome under the cashflow/tax value approach, the resultant lower after-tax returns would be likely to reduce investment in forestry, with undesirable environmental consequences. The Review notes that denying immediate deductions for the establishment costs of plantation timber would be inconsistent with the existing policy of encouraging planting of trees - important because of the associated environmental benefits.

In view of the existing policy, and consistent with the policy-based principle for exemption, the Review is not recommending a change to the current treatment of allowing immediate deductions for plantation establishment costs other than to the extent of any prepayments in accordance with Recommendation 4.4(ii).

The Review notes, nevertheless, that the current treatment has encouraged some end-of-year tax minimisation schemes. Some of the structural improvements to the law recommended by the Review should address, for the most part, the aggressive features of tax minimisation schemes - see the discussion under Recommendation 4.4.

Work in progress of service providers

Under the current law, providers of services for a fee (such as professionals, building contractors, tradesmen and the like) are not required to value their work in progress at year end to the extent that they are not entitled to bill for that work. Generally, that is not particularly distortionary as most service contracts tend to be of a short-term nature, so the income deferral is short. Indeed, the longer the contract, the more likely that the contract would be subject to periodic payments.

Work in progress of that nature can be difficult to value and to require taxpayers to do so could impose considerable compliance costs. However, providing a complete exclusion for such assets would not be appropriate as it could encourage taxpayers to enter into long-term arrangements for the provision of services on a deferred payments basis. Therefore, an exclusion will only apply if the work can reasonably be expected to be billed within 12 months.

Mining and quarrying exploration and prospecting expenditure

Applying the recommended treatment of expenditure and assets without recognising the valuation difficulties associated with the results of exploration and prospecting expenditure would mean that the tax treatment of this expenditure would depend on the results of the exploration or prospecting activity. Unsuccessful expenditure would be deductible at the time the activity was abandoned, while successful expenditure would enter the cost base of the project. That is the accounting approach.

It has been a longstanding feature of the current law to allow an immediate deduction for exploration and prospecting expenditure. Allowing continuation of immediate deductibility is justified on the basis that the value of the associated asset cannot be reliably measured.

Assets produced by expenditure on advertising

Most advertising expenditure is deductible immediately under the current law. The following are exceptions to that general rule.

- •

- Where the expenditure is for the acquisition of, or improvement to, an asset used for advertising purposes - for example, an advertising sign or hoarding. In such cases, the asset would be depreciable.

- •

- Prepayments of services to be rendered by another person where the service will not be completed within a period of 13 months. In that case, the expenditure is deductible over the period of time during which the service is to be rendered.

In many situations advertising expenditure may provide the dual benefit of enhancing both immediate sales and the value of future sales or goodwill. In practice, it would be extremely difficult to determine the extent to which expenditure on advertising that has been 'put to air' results in ongoing benefits beyond the period in which the advertising occurs.

The Review therefore believes that, consistent with accounting practice, there should be no attempt to recognise the value of an asset for tax purposes in respect of the end-benefits flowing from advertising. However, consistent with the treatment of expenditure and the proposed removal of the 13 months prepayments rule (see Recommendations 4.1 and 4.6), assets will be recognised where expenditure relates to:

- •

- the cost of a depreciable asset used for the purpose of advertising, such as an advertising sign; or

- •

- an advertising service or product to be provided or developed, at least partly, after the end of the year, such as a series of television advertisements.

Assets and liabilities receiving a tax value determination

Recommendation 4.4 - Determining tax values for individual taxpayers

|

That individual taxpayers be required to determine tax values for the following assets and liabilities:

|

Cash basis accounting for individuals

Under the current law, a cash basis of accounting has been applied for income derived by individuals primarily in receipt of employment-related income and/or ordinary interest and dividends.

Under the cashflow/tax value approach, the change in tax value of some assets and liabilities would have to be taken into account by some such individuals unless specifically excluded. The Review considers that individual taxpayers should continue to be taxed on a cash basis as a general rule. Some assets and liabilities will be valued for tax purposes and these are specifically listed.

Prepayments

In the case of prepayments, there will be no requirement to generally value such assets provided the payment does not relate to the provision of services or products over more than 12 months and the payment does not relate to a period which ends beyond the next income year. Typical prepayments which will be covered by this 12 month rule are annual subscriptions to professional or trade associations and for magazines and journals. This measure ensures, for example, that payments made in June to cover services over the following year of income will continue to be deductible in the year of payment.

Tax shelter arrangements

An exception to the 12-month prepayment rule will apply to advance expenditure incurred ('prepayments') in respect of participation or investment in arrangements or projects sometimes referred to as 'tax shelter schemes'. The type of arrangements intended to be covered include those that are the subject of product rulings issued by the Australian Taxation Office.

These types of arrangements generally involve participants incurring expenditure towards the end of an income year in respect of services to be provided over the following year. Income from such arrangements is not usually derived, if at all, for a number of years. In some cases, expenditure is partly financed by non-recourse loans - which means the investor is only liable to repay the loan from, and to the extent of, any proceeds from the sale of the product of the underlying asset.

Broadly speaking, under the current law these prepayments of up to 13 months are immediately deductible if they are not characterised as capital expenditure and provided the general anti-avoidance provisions do not apply. The current treatment of immediate deductibility and delayed income has encouraged some end-of-year tax minimisation schemes.

Under the Review's recommended treatment of expenditure and assets, some expenditure (including prepaid expenses) in respect of these types of investment arrangements will give rise to an asset, for example, a grapevine. In such cases, the expenditure will be included in the tax value of the asset and be written off in accordance with the write-off rules for the relevant class of asset. Whether expenditure gives rise to an asset on hand at year-end will depend on the facts in each case. The Review believes that such assets should be brought to account by individual taxpayers. Similarly, where expenditure such as management fees relating to these investment arrangements is prepaid, the prepayment should be allocated over the income years to which the payment relates (Recommendation 4.6).

The exception to the 12 month rule for prepayments relating to these arrangements or projects will affect the treatment of management fees paid at the end of the income year for services to be provided in the following year. The write-off of the expenditure for tax purposes will be allowed in the following year.

Where non-recourse funding results in expenditure on the investment scheme greater than identifiable project-related costs, such as management fees or development costs, the excess would appear to relate to an asset reflecting the future benefits from the project. That asset would not attract up-front deduction. It would fall in value to zero if no future benefits were, in the event, realised. If, in that event, the associated part of the non-recourse loan were also forgiven there would be no net tax effect under the recommended treatment of assets and liabilities (and under the matching arrangements involving debt forgiveness in Recommendation 6.8).

The structural improvements to the law recommended by the Review - including the treatment of prepayments - should address, for the most part, the key features of the tax minimisation schemes.

Financial assets and liabilities

Individuals will not be subject to accruals taxation unless the financial asset or liability provides significant tax deferral opportunities. These opportunities will exist where, to take the example of a financial asset that would be taxed on an accruals basis in accordance with Recommendation 9.2, the asset has a term of one year or more, and the return applicable to any effective discount is more than 1 per cent per annum, compounded annually. A similar accrual requirement under the existing tax law also applies to individuals. It means that, for example, if the annual return is wholly paid out during the income year, an individual does not have to apply accruals treatment to a loan.

The expression 'effective discount or premium' will cover deferred interest and similar situations (for example, where the capital is indexed to inflation). Subject to the 1 per cent and one year thresholds, the accruals rule will cover synthetic debt arrangements (see Recommendation 9.9).

Recommendation 4.5 - Determining tax values for small business

| That eligible taxpayers operating small businesses who elect to use the simplified tax system in accordance with Recommendation 17.1 be required to determine tax values for those assets and liabilities as specified in Recommendation 17.2. |

Simplified tax system for small business

The Review is recommending a simplified optional treatment for taxpayers operating small businesses. The simplified tax system will involve the exclusion of certain assets and liabilities from year-end tax valuation (see Recommendation 17.1).

Recommendation 4.6 - Prepayments

|

Repeal of 13-month rule

|

|

Apportionment principle

|

|

New 12-month rule for taxpayers accounting on cash bases

|

|

Transitional arrangements

|

Under the existing law an immediate deduction is allowed for advance expenditure incurred ('prepayments') relating to the provision of services to be rendered within 13 months. This 13 month rule for prepayments allows an inappropriate bringing forward of annual deductions and is inconsistent with the accounting practice of bringing prepayments to account as assets at year-end. Because of its tax deferral advantages, the rule has been used by some taxpayers as a key feature of a number of schemes and arrangements to avoid tax.

The current treatment of allowing immediate deductibility for prepayments provides inconsistent treatment between payers and payees. As a general rule, a prepayment is not included in the income of the taxpayer in receipt of the payment until the services to which the payment relates have been provided. In other words, income is not derived until it has been earned.

The Review's recommendation will ensure consistent treatment for both the payments and receipts. Consistent with accounting, the tax value of prepayments at the end of the year will be brought to account as an asset in the calculation of taxable income. The tax value of the services to be provided after the end of the year will be brought to account as a liability by the taxpayer receiving the prepayment.

In the case of individuals, and small business taxpayers who elect for the simplified tax system treatment, most prepaid expenses will only be treated as an asset at year-end if the prepayment relates to the provision of services or products over more than 12 months or extends beyond the end of the next year of income (see Recommendations 4.4 and 17.2). The existing 13 month rule is not appropriate because it allows the potential for immediate deductibility for expenses relating to services to be provided in three income years.

Transitional arrangements

Because of the potentially significant first year revenue impact on some taxpayers in having to account for prepayments as an asset, the Review is recommending a five year transitional rule in most cases. This means that taxpayers will be allowed to bring the tax value of the asset at 30 June 2001 evenly to account over five years.

The Review believes, however, that the five year transitional rule is not warranted for prepayments in respect of the tax shelter type projects or arrangements discussed at Recommendation 4.4.

Because of the recommended five year transitional measure combined with the reduction in the entity rate of taxation to 30 per cent in the 2001-02 year, some taxpayers might seek to exploit the transitional measure by inflating the amount of prepayments in the 2000-01 year. To prevent such exploitation and its resulting impact on revenue, the Review believes a further transitional measure is warranted.

The recommended measure will restrict the tax value of prepayments qualifying to be spread over five years to no more than an increase of 10 per cent over the amount of the deductions allowed for prepayments in the 1999-2000 income year.

Recommendation 4.7 - Tax values of trade debtors and creditors

| That, provided the terms of payment are within six months, the tax value of trade debtors and creditors be the nominal value of the amount to be received or paid. |

Taxpayers will be required to account for the tax value of debtors and creditors at year-end unless they are calculating taxable income using a cash basis treatment (Recommendation 4.4) or the simplified tax system (Recommendation 17.2). Terms of payment are generally within six months and hence the recommendation will ensure that the current treatment for bringing debts to account will continue in most cases.

Recommendation 4.8 - Certain assets now to be valued at year-end

|

Valuation of specific assets

|

|

Transitional arrangements for specific assets

|

Assets to be brought to account for the first time

The Review has identified some assets with trading stock characteristics that taxpayers currently do not have to bring to account at year-end even though expenditure in respect of the asset is deductible when incurred. Those assets can represent a significant part of the income base of some taxpayers so their current treatment is particularly distortionary.

Non-billable deliveries of products capable of reasonable estimation

Generally, providers of products such as gas and electricity are not entitled to bill customers until they have established the actual value of the product provided - that is, until they have read customers' meters. Under the existing law, the value of such assets (unbilled products) is not taxable until the asset matures into a recoverable debt. The value of such products, as well as the cost of providing them, is capable of being accurately estimated. Accounting principles also require that the non-billable portion of delivered products to be brought to account. In this case, the tax treatment should be consistent with the accounting treatment.

Consumable stores and spare parts

As noted under Recommendation 4.3, stores of consumables and spare parts are not generally treated as trading stock under the existing law and so do not have to be brought to account at year-end. Accounting requires year-end stores of such assets to be brought to account where amounts are material.

The Review is recommending that taxpayers will not have to account for the year-end stocks of consumable stores and spare parts where the aggregate tax value does not exceed $25,000 (Recommendation 4.3). Taxpayers will have to account for those assets where their aggregate tax value exceeds that limit, unless the cost of the items has already been absorbed into the tax value of other assets, such as trading stock.

Transitional arrangements

Consistent with Recommendation 4.6(d) relating to prepayments, because of the potentially significant first year revenue impact on some taxpayers in having to account for the abovementioned assets, the Review recommends a five year transitional rule. This means that taxpayers will be allowed to bring the tax value of those assets at 30 June 2001 evenly to account over five years.

Recommendation 4.9 - Assets and liabilities changing their character

|

Assets or liabilities commencing or ceasing to be private assets or liabilities

|

|

Assets commencing or ceasing to be listed assets for capital gains and loss-quarantining treatment

|

Assets and liabilities commencing or ceasing to be private assets

Private assets held or liabilities owed by individuals will be excluded from the tax base so that any gain or loss on their disposal will not be taxed (Recommendation 4.13).

Where a private asset held, or a private liability owed, by a taxpayer becomes a non-private asset or liability, there is a need to decide the tax value of the asset or liability at the time of the change. For example, if the tax value of an asset was its original cost, the resulting gain or loss on the eventual realisation of the asset would include any accrued gain or loss during the period the asset was held as a private asset. This is an inappropriate outcome.

Where a non-private asset changes to a private asset and therefore leaves the tax base, there is a corresponding need to ensure that any gain or loss on the asset to that time is brought to account.

To ensure the appropriate outcome in both situations, such assets and liabilities will be treated as entering or leaving the tax base at a tax value determined by their market value at the time of the change. This will provide a means of crystallising any gain or loss attributable to the private or non-private periods.

Assets commencing or ceasing to be listed assets for capital gains and loss-quarantining treatment

In some situations, non-private assets can commence or cease to be listed assets for capital gains and loss-quarantining purposes while continuing to be held by the same taxpayer. For example, where held by an individual or superannuation fund, land will be a capital gains asset unless it is trading stock (Recommendation 4.10).

Situations could arise where land is initially acquired for investment or other business purposes but converts to trading stock. For example, a taxpayer might acquire rural land for market-gardening purposes. As a result of urban growth, the taxpayer decides some years later that it would be more economic to put the land to residential use. Rather than simply selling the land for the best price, the taxpayer decides to develop the land into residential allotments and market the individual allotments. In that instance, the land is likely to become trading stock at the time of the decision to proceed with the development.

Correspondingly, land could be initially acquired as trading stock and subsequently converted into long-term investment. For example, a taxpayer could acquire land for the development of apartment buildings for re-sale. At that point, the land would be trading stock. Upon completion, the taxpayer decides to keep some or all of the apartments for long-term investment. At that time, the asset would no longer be trading stock.

Given the different treatment to be applied to listed capital gains assets compared with other assets - particularly where held by individuals and superannuation funds - capital gains and loss-quarantining treatment ought to apply to so much of the gain or loss in the above situations that is referable to the period that the assets are held as listed capital gains assets. In the case of entities, a change in character of an asset will only have an impact for loss quarantining purposes.

The correct outcome can be achieved by requiring taxpayers to value the asset at the time of change in its character, so identifying the unrealised gain or loss at the time (to be brought to account at the time of ultimate disposal). In the case where an asset converts from a long-term investment asset to trading stock, for example, the asset will be treated as having a tax value equal to that market value for the purposes of determining the capital gain or loss referable to the period that the asset was held as a listed asset.

Current treatment

The recommended treatment differs from that under the current law. A taxpayer holding an asset that changes its character to trading stock is treated as disposing of the asset and immediately re-acquiring it either for its cost or market value, at the taxpayer's option. The current approach has two major disadvantages:

- •

- it taxes unrealised gains if the taxpayer selects market value and that exceeds the asset's tax value at the time; and

- •

- it can allow capital losses to be converted into revenue losses if the market value of the asset is less than its cost and the taxpayer elects to value the asset at cost.

A taxpayer holding trading stock that changes its character to non-trading stock is treated as disposing of the asset and immediately re-acquiring it at its cost. That approach has the disadvantage of converting unrealised revenue gains and losses into capital gains and losses unless the taxpayer has valued the trading stock at other than cost.

Assets receiving capital gains and loss -quarantining treatment

Recommendation 4.10 - Assets receiving capital gains and loss-quarantining treatment

|

General principles

|

|

Nominated asset classes eligible for capital gains treatment

|

|

Assets subject to loss-quarantining treatment

|

Simplicity in the law will be served by the use of a common basis for defining assets which will receive capital gains treatment and for which losses will be quarantined. For those taxpayers receiving this treatment of gains (Recommendations 18.2 and 18.3), a common asset pool provides a balance against the ability to defer taxation through selective realisation of losses.

Significant reform to the existing quarantining provisions is limited by revenue considerations. The revenue consequences of abolishing quarantining of all capital losses would be prohibitive, due to both the accumulated value of existing capital losses and the ongoing incentive to realise assets selectively.

Assets where a change in value is taxed on a realisation basis would account for the majority of assets held by individuals and a significant proportion of assets held by superannuation funds. Defining access to capital gains treatment and quarantining of capital losses in terms of the assets described in the recommendation aligns, broadly, with the 'capital' asset distinction in the existing law. Nevertheless, there would be some notable differences. In particular, losses on shares and land would be quarantined in a wider range of circumstances due to the removal of the existing distinction between 'revenue' and 'capital' assets.

Given the broad correspondence with existing capital gains assets, the listed asset classes should also define the pool of capital gains against which existing capital losses and future losses on existing assets can be applied - subject to private asset losses being restricted to gains on like assets (paragraph (d)) and the transitional measure in Recommendation 4.11.

Trading stock

Trading stock will continue to be excluded from capital gains treatment on the basis that such treatment would be counter to the objectives of encouraging investment in longer term capital assets and be inconsistent with the existing concept of taxing income from trading activities. The inclusion of trading stock assets in loss quarantining would undermine the integrity of capital loss quarantining.

Shares

In the case of shares and other membership interests, there is little conceptual or practical basis upon which to distinguish assets held for trading or investment purposes. Such assets are not included in the definition of trading stock, which is restricted to tangible assets (Recommendation 4.16).

One approach considered by the Review was to have an arbitrary time-based distinction between trading assets and investment assets. Allowing taxpayers the opportunity to realise losses on shares held for up to 12 months (after which time gains by certain taxpayers are subject to capital gains treatment) and not quarantining those losses would be likely to impose a significant cost to revenue. Even allowing a shorter period for loss quarantining purposes would provide adverse selection opportunities resulting in too great a revenue cost.

Rights

As a general rule, rights will be excluded from capital gains treatment, unless the granting of a right results in the permanent disposal of an underlying asset, or part of an underlying asset, that is eligible for such treatment. Capital gains treatment of rights would only apply where there is a permanent disposal of the underlying asset that is subject to the right.

Most depreciable assets would not qualify for capital gains treatment due to the annual deduction for their change in tax value. However, in the case of buildings not depreciable under the general depreciation regime for depreciable assets (Recommendations 8.12 and 8.13), both the building and the land would be classified as realisation assets and, hence, would continue to be subject to capital gains treatment and quarantining of losses.

Recommendation 4.11 - Quarantining of losses on existing CGT assets

|

Quarantining principle for existing CGT assets

|

|

Transitional provision for unusable losses

|

At present some taxpayers have realised capital losses which have not been absorbed. Where those taxpayers also have revenue assets such as shares, those capital losses cannot be applied against gains on the revenue assets. The proposed removal of the 'revenue' asset/'capital' asset distinction would allow those capital losses to be applied against gains on revenue assets. Any currently unrealised capital losses could also be applied when realised against revenue gains.

While the short term revenue impact of allowing the application of capital losses against revenue asset gains is difficult to measure precisely, it could be significant. The two main types of assets that are of relevance in this regard are shares and real estate. Of these, the principal source of potential revenue loss is likely to be from shares. The Review is therefore recommending that capital losses on assets acquired before 1 July 2000 will not be able to be offset against gains from existing shares held as revenue assets or trading stock and shares acquired on or after 1 July 2000. This recommendation will only apply to those taxpayers which have shares taxed as revenue assets or trading stock under the existing law.

If capital losses are prevented from being absorbed solely because of this recommendation, up to 20 per cent of those losses will be able to be utilised against gains on shares in any one year commencing from the 2005-06 year. For example, this transitional provision would apply if a taxpayer did not have capital gains assets other than shares.

Relatively few taxpayers are expected to be affected by this recommendation. The main impact would be on a few large companies. Further, the restrictions imposed under this measure are not likely to have a significant adverse impact on taxpayers relative to their treatment under the existing law.

Clarifying the treatment of private receipts, expenditures and assets

Recommendation 4.12 - Private receipts and expenditures

|

General principle

|

|

Specific exceptions

|

An important design issue for business taxation is the business/private dividing line defined by the treatment of private receipts, expenses and assets. This dividing line was given only preliminary attention in A Platform for Consultation.

Private receipts and expenditures in concept apply to individuals only and not entities. Restricting private receipts and expenditures to individuals will mean that all expenditure undertaken by entities will reduce taxable income either immediately or in future years unless precluded by a specific adjustment in the tax law.

In order to achieve the correct treatment of expenditure by entities, benefits provided by entities to employees or members should be taxed as income received at fair market value. Hence, the broad definition of a distribution from an entity contained in Recommendation 12.1 and maintenance of comprehensive fringe benefits taxation - or its replacement as recommended by the Review (see Recommendation 5.1) - are crucial to the proposed restriction of private expenditures to individuals.

Under the cashflow/tax value approach, the resulting treatment of expenditure broadens the scope of expenses that could reduce taxable income. Specifically, it is intended to allow a wide range of blackhole expenses to be deductible as a matter of principle. However, individuals' expenditure which is essentially of a private nature will continue to be non-deductible. To avoid any doubt, the new law will ensure that particular expenses (such as normal travel to and from work and certain self education expenses) will continue to be treated as private expenditure.

There will be some inconsistencies in the treatment of benefits received by employees and members of entities. For example, largely for compliance cost reasons, benefits received in the form of employer provided car parking (Recommendation 5.3) and the use of a residence held by an entity (where the related expenses are not deducted - Recommendations 12.25 and 12.26) will not be taxed in the individual's hands.

Recommendation 4.13 - Private use of assets

|

General principle

|

|

Depreciable assets

|

|

Land and buildings (other than a taxpayer's main residence) held by an individual

|

|

Collectables and other non-depreciable tangible assets (other than land) held by an individual at least partly for private use

|

Taxation of assets used partly for private purposes

Assets can generate three types of income - capital gains, current income and non-monetary income, the latter component reflecting the market value of benefits derived from the private use of an asset. Both the current income and capital gains represent part of the monetary income of the asset. There is a compelling case - based on revenue and compliance grounds - for excluding from the tax base the non-monetary income (and any private receipts) that reflects the private use of an asset and the corresponding proportion of expenses incurred in relation to that use.

Difficulties in determining the annual value of the capital gain and non-monetary components of income for many assets preclude a single practical rule for apportioning expenses between the private and non-private use of an asset. Hence, different approaches are required to apportion expenses associated with different types of assets where they are held at least partly for private use.

Assets held for private purposes are taxed in a variety of ways under the present law, in terms of the treatment of both expenses and capital gains and losses. Assets held primarily for private purposes are taxed under different provisions from those held only partly for private purposes. The approach recommended by the Review will achieve a more consistent treatment of assets used for private purposes while replicating the existing treatment to a substantial extent.

Current treatment of assets used privately

Assets, other than a taxpayer's main residence, that are used for private purposes receive one of three separate tax treatments under the current law.

- •

- Personal use assets - items other than land and buildings or collectables held primarily for the private use and enjoyment of the taxpayer - are subject to capital gains tax if their purchase value exceeds $10,000. There is no allowance for capital losses or expenses.

- •

- Collectables - items such as artworks, antiques and collections - are subject to capital gains tax if their purchase value exceeds $500. Capital losses on collectables are quarantined to capital gains on collectables and there is no allowance for expenses related to those assets.

- •

- Other assets held for private use, such as land and buildings, and other assets not held primarily for private use, are subject to capital gains tax and losses are treated as ordinary capital losses. If those assets were acquired after 20 August 1991, recurrent costs (including interest expenses) are capitalised into the cost base of the asset - or deducted as incurred against any recurrent income generated by the asset. Such costs cannot give rise to a capital loss.

A capital gain or loss in respect of an individual's main residence is generally ignored for tax purposes under the current law.

Proposed treatment of assets used privately

Under the proposed approach, the concept of a 'personal use asset' and the discontinuities between the treatment of assets used partly or primarily for private purposes will be removed. Broadly, an asset other than land will be a private asset if the asset is held and used by an individual solely for private or domestic purposes and, except if the asset is a depreciable asset that is not also a collectable, its cost is not more than $10,000.

Depreciable assets

Depreciable assets will be treated in a manner similar to the present treatment. Expenses and that part of the balancing adjustment relating to the private use of the asset will be excluded from the calculation of taxable income. The exclusion of expenses and any loss in value associated with the private use of a depreciable asset reflects the fact that the benefit derived from those costs is not taxed.

Land and buildings

For land and buildings acquired after 30 June 2000, the recommended approach requires for tax purposes the separation of the land from any structures. The required information will be available for structures commenced to be constructed after 30 June 2000, as a consequence of the proposed separation of land and buildings for the purposes of a sounder treatment of building depreciation (Recommendation 8.12).

The treatment for land will be similar to that which currently applies, with directly attributable expenditures (including interest and rates) being added to the tax value of the asset to the extent that the land is not used for income producing purposes (other than a capital gain on realisation). One difference will be that expenses included in the tax value of land could give rise to a loss on disposal, whereas at present such costs can be used only to offset a gain.

Expenses associated with structures attached to the land will be apportioned on the basis of the private and non-private usage of those assets, as for other depreciable assets used partially for private purposes. This differs from the present treatment where all non-capital costs of ownership for land and buildings are included in the cost base of the combined asset. Costs attributable to the building will not be capitalised except for the capital costs of acquisition and improvement. This approach is consistent with the treatment for other depreciable assets. The changed approach will apply only to buildings acquired or constructed after 30 June 2000.

As an example, in the case of a residential property used one-third of the time for private purposes and two-thirds of the time for income producing purposes:

- •

- two-thirds of the annual expenses attributable to the land (such as interest and rates) will be deducted in calculating taxable income in each year and one-third will be added to the tax value of the land; and

- •

- two-thirds of the annual expenses associated with the building and use of the land (such as maintenance, variable costs and overheads) will be deducted with the remaining one-third not taken into account in calculating taxable income or the tax value of the building or land.

Collectables and other assets held at least partly for private use

Recommendation 4.13(f) will result in one regime for collectables and other non-depreciable assets held for private use. There will be only one threshold acquisition amount for capital gains treatment.

Collectables and other non-depreciable assets on hand on 1 July 2000 will be covered by the new regime. Therefore, existing collectables acquired for more than $500 but no more than $10,000 will no longer be subject to capital gains treatment when realised.

The treatment for collectables held by an individual (other than as trading stock) and other non-depreciable tangible assets held by an individual (other than land) will be different from the present treatment in several respects. For collectables, the main difference is that the threshold acquisition value for capital gains taxation will be increased from $500 under the present law to $10,000. For other non-depreciable assets (apart from land), the main difference lies in having a single treatment for assets used at least partly for private purposes, rather than a separate treatment for assets used partly for private purposes and those used primarily for private purposes.

Limiting deductibility of annual expenses to the extent of recurrent income earned from the asset in the same year, though somewhat arbitrary, provides an objective test upon which to base the apportionment of expenses.

Recognising that losses on collectables and other non-depreciable assets held by individuals partly for private use could reflect, in part, the private use of the asset, losses on those assets will be quarantined to gains on like assets. Collectables held by an individual as trading stock will be excluded from this treatment.

Providing deductibility for blackhole expenditures

Recommendation 4.14 - Deductibility provided for blackhole expenditures

|

General principle

|

|

Statutory deeming of economic life

|

A range of expenditures (blackhole expenditures) is treated inappropriately under current tax law in that the expenditures are either not deductible or not deductible in a manner consistent with their economic characteristics (see A Platform for Consultation at pages 100-102).

Under the cashflow/tax value approach to determining taxable income, blackhole expenditures will be treated in a manner consistent with their economic characteristics. Specifically, such expenditure will be either expensed, amortised or capitalised.

- •

- If the expenditure does not form part of the tax value of an asset or does not reduce a liability, it will, in effect, be immediately deductible.

- •

- Some blackhole expenditures will have the effect of improving a non-depreciable asset, in which case the expenditure will be added to the tax value of the asset. The tax effect would be to reduce the taxable gain (or increase the allowable loss) when the asset is disposed of.

- •

- If the expenditure is related to a depreciable asset, the existing blackhole expenditure will be written off by reference to the effective life of the asset. In other cases, while the asset arising from the expenditure is a wasting asset ultimately having no value, it may not be obviously related to other assets of the taxpayer that are recognised for tax purposes. Statutory write-off is relevant in these cases.

Different treatments of blackhole expenditures

Immediate deduction

A range of blackhole expenditures do not have an enduring value or the enduring value cannot be reasonably estimated. Under the cashflow/tax value approach, such expenditures will be immediately deductible. Whether an item of expenditure fits within this category would depend on the particular facts and circumstances.

The following are examples of blackhole expenditure that generally will be immediately deductible because they would not form part of the tax value of an asset:

- •

- costs of defending title to an asset (including native title claims) where claims over the title are lodged while the person owns the property;

- •

- costs of defending a takeover, whether successful or not;

- •

- costs of winding-up or closing a business;

- •

- expenditures that contribute to the creation of business goodwill, such as business relocation costs and market development costs unless the expenditures give rise to, or improve, a recognisable asset;

- •

- costs of an unsuccessful takeover (deductible at the time of abandonment of the action) such as the costs of preparing takeover documents to obtain a strategic stake in a target company (but not the costs of shares acquired and associated expenses); and

- •

- costs of demolishing an asset which has been held by the taxpayer for the purposes of producing income other than a capital gain on the associated property.

Not deductible until asset is disposed of

Some blackhole expenditure has the effect of improving a non-depreciable asset, in which case the expenditure will be added to the tax value of the asset. In such cases, the tax effect would be to reduce the taxable gain (or increase the allowable loss) when the asset is disposed of. Expenditures falling into this category include:

- •

- costs of demolition that have the effect of improving the underlying property beyond its condition at the time it was acquired;

- •

- costs of landscaping and other earthworks to be maintained on an indefinite basis;

- •

- costs of successful feasibility studies relating to non-wasting assets;

- •

- costs of successful takeovers; and

- •

- costs of defending title to an asset (including native title) if the asset was acquired with the knowledge that the title, or other rights over the asset, were in dispute - otherwise this expenditure would be immediately deductible.

Amortisation

Expenditures that will attract write-off according to the effective life of the associated depreciable asset include:

- •

- costs of successful feasibility and environmental impact studies relating to depreciable assets;

- •

- costs of ornamental trees and shrubs; and

- •

- contributions to local or regional infrastructure as a condition for constructing depreciable assets.

Other write-off arrangements

The write-off arrangements for a range of other expenditures that might be considered to be blackhole expenditures are covered in the proposed treatment of leases and rights. These expenditures include lease premiums, franchise fees and the cost of acquiring indefeasible rights of use.

Some expenditures give rise to an asset which will cease to have value at some time but whose life is indeterminate and do not obviously relate to other relevant assets of the taxpayer that are recognised for tax purposes. Examples of such assets include business start-up costs, such as:

- •

- costs of establishing an entity, including company pre-incorporation expenses such as legal expenses and statutory charges; and

- •

- costs of raising equity and borrowings for an indefinite period (for example, prospectus and underwriting costs).

Under the existing law, the costs of borrowing are eligible for write-off over the lesser of five years or the duration of the borrowing. In contrast, the costs of equity raising are blackhole expenditures, despite the similarities of a borrowing to an equity raising. For example, a business can choose to raise additional capital either through a perpetual floating rate note or new equity. There is thus a strong case for applying the same taxation treatment to all forms of capital raising expenses.

The existing law treatment of a maximum 5-year statutory write-off for the borrowing costs would be an appropriate basis to write off the costs of raising equity.

Pre-incorporation expenses have similar attributes to capital raisings as they can be necessary prerequisites for commencing a business. The Review considers that these expenses should be accorded a 5-year statutory write-off.

The Review may not have identified all expenditures for which the statutory write-off would be appropriate. The recommendation to include other expenditures (and their write-off period) under the Income Tax Regulations, as they are identified, will facilitate the future operation of the law.

Feasibility and similar studies

In some cases, it is not evident at the time of incurring expenditure whether or not it will produce either an asset, or an improvement to an asset - for example, a feasibility, environmental impact or market study. If the study is abandoned, there would be no asset and its cost will become deductible at that time. If the project proceeds, the expenditure will be included in the tax value of the assets associated with the project.

General deductibility of interest

Recommendation 4.15 - General deductibility of interest

|

General provisions

|

|

Payment of tax liability

|

The treatment of interest expenses under the current law differs depending upon whether the expense is incurred:

- •

- before an income earning activity;

- •

- in connection with the earning of capital gains; or

- •

- as part of the process of earning recurrent income.

In practice, these principles of deductibility are difficult to apply consistently due to the fungible nature of debt. This results in uncertainty and increased compliance costs, such as in seeking rulings to clarify the treatment of interest in relation to major investment projects.

The recommended treatment will significantly reduce the current uncertainty surrounding interest deductibility. It will also result in more equitable treatment for taxpayers.

As noted in A Platform for Consultation (page 44), interest should not be viewed simply as a cost of earning recurrent income. It is better viewed as the cost of maintaining access to the capital funds underlying a business. The financial liability base of a business can be viewed similarly to, but separately from, the real asset base of a taxpayer. Given that interest expenditure does not directly change the value of the asset base of the taxpayer, it is appropriately deductible in the year incurred - other than to the extent to which the interest is prepaid thereby resulting in an asset on hand at the end of a year.

Interest in respect of borrowings by entities to finance distributions of equity and dividends, or to finance tax liabilities, will not be private expenditure (Recommendation 4.12) and will therefore reduce taxable income in the year incurred. This measure will remove the need to identify the purpose and use of any borrowings by an entity, other than in connection with the earning of exempt income. In practice, many business taxpayers are currently able to arrange their affairs to ensure immediate deductibility of interest on borrowings essentially used to pay tax.

General deductibility for interest will not extend to borrowings by individuals against assets where the purpose or use of those borrowings is to finance private expenditure. In other words, the existing purpose or use tests will continue to apply for individuals.

The current treatment of interest on borrowings in respect of land held by individuals for private use - capitalisation of interest expenses - is also to continue (Recommendation 4.13(d)).

In the international arena, conditional on the Review's thin capitalisation proposals in relation to Australian multinational investors (Recommendation 22.6), interest deductibility will no longer be denied for interest expenses incurred in earning foreign source income.

To maintain equity with the treatment for entities, it is appropriate that interest in respect of borrowings undertaken by individuals to meet their tax liabilities not be treated as a private expense. In practice, most individual taxpayers do not need to borrow to pay tax liabilities because tax is generally deducted at source.

Definition and valuation of trading stock

Recommendation 4.16 - Definition of trading stock

|

That trading stock be defined as:

|

The possibility of removing the current arbitrary and uncertain differentiation between trading stock, 'revenue' assets and 'capital' assets was canvassed in the Overview of A Platform for Consultation (page 42). Options for valuing trading stock were canvassed in Chapter 3 of A Platform for Consultation.

The cost of purchasing or manufacturing trading stock during a year reduces taxable income - and the tax value of any of this trading stock held at the end of the year adds to taxable income. This treatment of expenditure on trading stock is the same in practice as that proposed under the cashflow/tax value approach. As such, the retention of the existing concept of trading stock is not required simply for the purposes of applying that approach.

Where the concept of trading stock, nevertheless, remains relevant is in defining the manner in which assets that are held by a business for trading purposes should be taxed. In particular, consistent with the treatment under existing law, gains on disposal of trading stock assets should not be eligible for capital gains tax treatment while losses on such assets should not be subject to quarantining (see Recommendation 4.10). Capital gains tax treatment is aimed at encouraging investment while quarantining of losses is designed to limit the consequences of selective realisation of capital gains and losses. Neither of these aspects of the treatment of capital gains and losses is relevant to trading stock assets.

As against the definition of trading stock in the current law, the proposed definition:

- •

- excludes intangible assets, such as shares and other financial assets; and

- •

- includes interests in trading stock, such as those held by joint venturers and partners.

In the case of financial assets, it is both conceptually and practically difficult to distinguish between individual items on the basis of whether they are held for trading or investment purposes - hence, the recommended targeting of the trading stock definition to tangible assets. Financial services entities often account for their trading activities on a mark-to-market basis and their investment activities on an accruals or realisation basis. The proposed elective market value regime for tax purposes (Recommendation 9.1) will allow financial services entities to achieve a match between tax and accounting treatment.

Interests in trading stock of members of unincorporated joint ventures and ordinary partnerships will also be treated as trading stock. Under Recommendation 16.16, a fractional interest approach to computing taxable income will apply to such structures unless the members elect to apply a joint approach. Under the fractional interest approach, members will account separately for their interests in trading stock.

Trading stock will also include land (including land held under a long term or perpetual lease granted by the Crown) currently defined as trading stock and livestock held for the purpose of primary production.

Recommendation 4.17 - Tax values of trading stock assets

|

Tax valuation methods

|

|

Asset classes

|

|

Variation of election

|

Tax valuation methods

The method of valuation can change from year to year for an individual item of stock, subject to the requirement that the opening value for an item is equal to its previous closing value. As discussed in A Platform for Consultation (page 127), this degree of flexibility provides the scope for taxpayers to manipulate the valuation of trading stock for tax minimisation purposes. Nevertheless, some flexibility in the valuation of trading stock is warranted where such assets would typically be expected to decline in value due to obsolescence or deterioration or where the use of cost would impose undue compliance costs on the taxpayer.

For trading stock the default valuation option will be the lower of cost or net realisable value, the accounting method of valuing inventories. This will allow for reductions in the value of trading stock assets due to obsolescence or deterioration.

The concept of net realisable value is the same as for accounting (Accounting Standard AASB 1019 'Inventories'). Broadly, it means the estimated proceeds of sale net of all further costs of completion (where applicable) and costs of selling.

Apart from the default treatment, taxpayers will also continue to have the option of valuing trading stock at market selling value.

Asset classes

Elective valuation on the basis of asset class allows flexibility yet limits the potential cost to revenue associated with selective valuation of assets on a transaction-by-transaction basis or on an annual basis. To achieve this, once an asset class is defined and a method of valuation other than the lower of cost or net realisable value elected, all such trading stock assets in that class held by a taxpayer will be required to be valued using the elected market valuation.

Taxpayers will be able to specify their own asset classes, subject to some restrictions. This approach will provide flexibility to taxpayers and avoid obvious difficulties associated with attempting to define classes of assets in legislation. An asset class will need to be defined on the basis of readily identifiable characteristics of the included assets.