Explanatory Memorandum

(Circulated by authority of the Assistant Treasurer and Minister for Financial Services, the Hon Stephen Jones MP)Attachment 2: Impact Analysis - Buy Now, Pay Later

Executive Summary

This Impact Assessment sets out the problems, policy objectives, consultation processes, options for reform, an analysis of those options, and implementation and post-reform evaluation processes, in relation to buy now pay later credit products.

There have been widespread concerns raised by consumer groups, regulators and academics – supported by various studies and surveys – that some BNPL borrowers are experiencing financial stress after being extended credit they cannot afford. Other possible consumer harms include those arising from poor complaint handling processes, cases of disproportionate fees, undesirable marketing practices, financial abuse and poor or inconsistent pre-contractual product disclosures.

BNPL products are currently not regulated under the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Credit Act), although some other consumer protection laws apply. Industry self-regulation has been only partially effective due to incomplete coverage of the industry Code of Practice, a lack of rigour in some industry commitments, insufficient compliance with some commitments and a lack of mechanisms to penalise or exclude bad actors.

Following the Government's announcement on 12 July 2022 that it would be examining whether the regulation of BNPL should be reformed, Treasury held targeted bilateral meetings with 28 stakeholders to inform public consultations (including roundtables) on an options paper "Regulating Buy Now, Pay Later in Australia", from 21 November 2022 to 23 December 2022. 77 written submissions were received. Further roundtables and bilateral meetings were held in early 2023 with community groups, industry, regulators and academics.

The options consulted upon included:

- •

- Option 1: A government-industry co-regulation regime, relying on a stronger BNPL Code of Practice with a legislated bespoke affordability test for BNPL products.

- •

- Option 2: A modified application of the Credit Act, allowing for more flexibility and technological neutrality, with Responsible Lending Obligations (RLOs) scaling more appropriately to the risks associated with BNPL.

- •

- Option 3: Full unmodified regulation of BNPL under the Credit Act, including licensing and the wholesale application of the existing RLOs.

Feedback resulted in a proposal to adopt Option 2, with increases in some regulatory settings to more closely resemble Option 3. These included closer alignment of the application of the Credit Act and Credit Code to BNPL and increased rigour in RLOs including setting floors in its scaling.

It has been assessed that:

- •

- Option 1 would fail to effectively mitigate the existing negative impacts on consumer welfare.

- •

- Option 2 would deliver significant net benefits to consumers through improved consumer protection, while still enabling efficient and convenient lending practices by BNPL providers. It would maintain the principle based RLO framework to ensure BNPL is not provided to those whom it is unsuitable but ensure that this regulation is proportionate to the risks associated with the product.

- •

- Any increase in consumer protections from Option 3, over those for Option 2, would be exceeded by reductions in the benefits to merchants, providers and consumers (including financial inclusion) due to the additional regulatory burden and consumer experience impacts.

The regulatory impact of adopting Option 2 has been estimated at:

| Average annual regulatory costs | ||||

| Change in costs ($ million) | Individuals | Business | Community

organisations |

Total change in cost |

| Total, by sector | $4.09 | $10.91 | Nil | $15.00 |

Legislation is required to bring BNPL providers within the scope of modified Credit Act regulation.

Reforms would be evaluated by Treasury against statistical data on unaffordable lending and other consumer harms, supplemented by anecdotal feedback from consumer and industry representatives. This would occur after a suitable period has passed post commencement to allow for the reforms to become established and for the collection of sufficient data on post-reform outcomes.

Background

What is Buy Now, Pay Later?

Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL) products are an alternative to more traditional forms of credit. They allow consumers to budget their spending by paying off goods and services in instalments at a comparatively cheaper cost than a credit card or short-term loan.

Buy Now, Pay Later arrangements:

- •

- involve a third-party financing entity;

- •

- provide consumers finance to pay for purchases of goods, services and bills;

- •

- do not provide consumers cash;

- •

- do not charge interest on the finance used;

- •

- may charge consumers low fixed fees for using the finance;

- •

- may charge merchants service fees for accepting BNPL; and

- •

- pay the merchants the value of the purchase upfront, less any fees, and collect repayments from consumers in instalments.

The BNPL sector has been rapidly growing since its emergence in around 2015, when entities like Afterpay and ZIP began offering services to consumers to purchase discretionary small retail items, such as clothing and fashion items. Since then, BNPL has continued to evolve and expand to new products and service offerings. 15 BNPL providers currently operate in the Australian market, including new startups (such as PayRight), established financial institutions (such as the Commonwealth Bank) and financial technology companies (such as PayPal).

The Australian Finance Industry Association's (AFIA) 2022 industry report found that an average BNPL consumer uses a BNPL product 18.2 times a year and spends an average of $136 per transaction.

What are the benefits of BNPL?

BNPL products have driven positive outcomes for consumers, merchants and the economy, offering an innovative, convenient and relatively low-cost alternative to traditional forms of credit such as credit cards, payday loans and consumer leases.

Benefits to consumers

Consumers have benefitted from greater access to a relatively cheap credit product that is easy to use and which allows consumers to smooth their consumption over time.

Data from the Reserve Bank of Australia's (RBA) Payments System Board shows that consumers continue to take up BNPL products at a high rate. Between 2021-2022, the RBA found there were approximately 7 million active BNPL accounts (which includes persons holding multiple accounts) and $16 billion in transactions, an increase of approximately 37 per cent on the previous financial year. This was equivalent to 2 per cent of credit card purchases in Australia by value that year.

BNPL has also driven some consumers to shift away from expensive, higher risk credit such as payday loans and towards cheaper and lower risk BNPL credit. For example, the National Credit Providers Association (NCPA) found that applications for Small Amount Credit Contract (SACC) loans have declined by over 11 per cent in the past financial year. The NCPA partially attributes this decline to BNPL products taking away market share.

Benefits to merchants

AFIA's January 2023 report, The Economic Impact of Buy Now, Pay Later in Australia – Update, found that BNPL has grown in popularity among merchants, with more than 158,900 businesses accepting BNPL – an increase of 17.4 per cent from the previous financial year.

According to AFIA, in 2022, acceptance of BNPL created an additional $2.7 billion in new revenue for these retailers through new customer acquisition, increased basket sizes and increased customer satisfaction and retention. This represented an increase of 28.6 per cent from the 2021 financial year ($2.1 billion).

AFIA's 2022 Research Report also found that merchants surveyed experienced an average increase of 5.6 percent in their revenue due to BNPL services.

Benefits to the economy

BNPL has also benefitted the broader economy by increasing competitive pressure on traditional credit products, such as credit cards. This has resulted in some large banks offering their own BNPL products, or low-fee, low-limit credit cards as an alternative.

In addition, BNPL has been an Australian fintech success story given the fact that domestic BNPL providers have exported their business models internationally, such as Afterpay.

How is BNPL regulated?

While the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Credit Act) is the primary legislation governing consumer credit products, the Credit Act only applies to credit provided under a contract where:

- •

- there is a deferral of a debt or a payment of a debt;

- •

- the credit is provided to a natural person or a strata corporation;

- •

- the credit is predominantly for personal domestic or household use, or for purposes relating to investment properties; and

- •

- there is, or may be, a charge imposed upon the borrower for providing the credit.

This means that credit products and services, such as invoicing services and BNPL products which do not charge any fees (excluding late or missed payment fees), [67] fall outside the regulatory scope of the Credit Act.

Other BNPL products typically operate under the Credit Act's exception for interest-free continuing credit contracts [68] which only charge periodic or other fixed consumers fees for the provision of credit below prescribed fee caps of $200 in the first 12-months and $125 for any subsequent 12-month period thereafter. [69] Most BNPL products charge small service fees, such as account establishment fees and account keeping fees, in a way that allows them to operate under this exception.

Given BNPL either falls outside the Credit Act's definition of 'credit' or falls within one of its exceptions, BNPL is not subject to Responsible Lending Obligations (RLOs). RLOs require providers to assess whether a credit product or credit limit increase is not unsuitable for a consumer by gathering and considering information about the consumer's financial circumstances, as well as taking reasonable steps to verify that information. [70]

Under the unsuitability test, a credit product is unsuitable for a person, if it is likely that:

- •

- the consumer will be unable to comply with their financial obligations; or

- •

- the consumer will only be able to apply with their financial obligations with substantial hardship; and/or

- •

- the product will not meet the consumer's requirements or objectives.

Other Credit Act provisions that do not apply to BNPL providers include:

- •

- holding an Australian Credit Licence (ACL);

- •

- information and product disclosure obligations;

- •

- internal and external dispute resolution obligations;

- •

- hardship arrangement obligations;

- •

- termination, enforcement and debt collection restrictions;

- •

- marketing and other miscellaneous restrictions; and

- •

- some but not all of the Australian Securities and Investment Commission's (ASIC) information gathering powers.

What consumer protections are currently in place for BNPL?

While BNPL products are exempt from certain consumer protections in the Credit Act, such as the RLOs, they do exist within the broader regulatory framework covering financial products.

The regulatory frameworks that apply to BNPL include:

- •

- The Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (ASIC Act) provides general financial services consumer protections (e.g., misleading and deceptive conduct) that apply to all financial products regulated by Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC), including BNPL.

- •

- Some parts of Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Corporations Act), including the Design and Distribution Obligations (DDO) and the Product Intervention Powers (PIP).

- •

- Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Australian Consumer Law), which covers some BNPL provider conduct not covered by the ASIC Act, including provisions around unsolicited supplies, pricing and information standards.

- •

- The Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Act 2006 (AML/CTF Act), includes obligations to conduct customer identification and verification procedures, record keeping, reporting suspicious matters and providing periodic compliance reports. The AML/CTF Act also requires reporting entities to have an AML/CTF framework in place covering money laundering and terrorism financial risk assessments.

Australian Finance Industry Association (AFIA) BNPL Code of Practice

AFIA issued a BNPL Code of Practice as an industry response to a recommendation for industry selfregulation by the Senate Economics Reference Committee's inquiry into Credit and Financial Services Targeted at Australians at Risk of Financial Hardship in February 2019. The Code came into force on 1 March 2021. It is estimated that 90 per cent of BNPL accounts are provided by Code signatories.

The Code aims to increase consumer protections by requiring providers to conduct tiered suitability tests for transactions above $2000, to offer hardship provisions and adhere to warning and communication requirements.

The Code is contractually enforceable against Code members and is enforceable by consumers through the Australian Financial Complaints Authority (AFCA).

1. What is the problem you are trying to solve?

Problem statement: How can the Government address instances of consumer harm arising from the use of BNPL products, predominately due to unaffordable lending, and also maintain the benefits of competition and financial inclusion that BNPL provides?

Surveys, research and stakeholder feedback indicate that there are significant problems in relation to unaffordable lending and BNPL (although this is mostly concentrated among low-income individuals, particularly those with existing debts), plus poor hardship and dispute resolution practices of some BNPL providers. To a lesser degree, there are indications that problems also exist in some cases in relation to BNPL with excessive fees, product disclosure, transparency of indebtedness and competitive neutrality.

Unaffordable lending is generally taken to mean credit extended to consumers that they are unable to pay back or are only able to pay back with substantial hardship. Some signs that unaffordable lending may be occurring are the level of financial stress indicators, the level of consumer hardship requests, the level of arrears or bad debt provisions and the extent to which consumers have to cut back spending on essentials or default on other credit products in order to repay BNPL loans.

Some vulnerable BNPL consumers have been the subject of unaffordable lending practices

Certain consumers of BNPL products have experienced increased levels of financial stress due to entering loans which they cannot afford to repay without undue hardship.

There has been strong and consistent negative feedback from the financial counselling community on the level of unaffordable BNPL lending that they are witnessing in relation to their client groups. The Government's consultation received a series of case studies from consumer groups that highlighted situations where vulnerable consumers were being extended BNPL credit that they could not afford. The consultation found, particularly through qualitative evidence submitted by financial counsellors, that unaffordable lending appeared to be concentrated among vulnerable consumers, who are typically low-income individuals (in particular, those on social security), including those with multiple existing BNPL debts, SACCs, consumer leases or unregulated high-cost loans.

The harm resulting from unaffordable lending is partially mitigated by the common BNPL business model which provides low amounts of credit, caps fees, charges relatively low amounts of maintenance and default fees, deactivates consumers' accounts upon default, does not report defaults to reporting agencies and readily writes off debts which cannot be resolved.

As described by the data below, despite the relatively overall comparable levels of risk of unaffordable lending, maintaining the status quo would likely see more vulnerable cohorts of consumers continuing to be affected by unacceptable levels of unaffordable BNPL lending. In particular, the exception of BNPL providers from compulsory RLO checks means that BNPL providers do not need to be aware of any other existing debts incurred by consumers, including on other BNPL providers' platforms. Consumers can therefore incur relatively large amounts of credit debt in comparison to their available income, in the range of thousands of dollars, with little restrictions.

2022 ASIC consumer monitor (data on 16 May 2022)

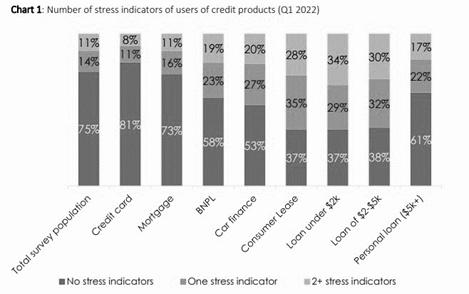

ASIC's unpublished consumer monitor survey for Q1 2022 found 19 per cent of BNPL consumers experienced two or more financial stress indicators (using the Household Income and Labour Dynamics financial stress methodology), compared to 11 per cent of the total survey population. This is a similar level of financial stress to car loans (20 per cent) and personal loans above $5,000 (17 per cent). In comparison, 8 per cent of credit card users experienced two or more financial stress indicators. Most BNPL products are functionally similar to credit cards, although with significantly shorter repayment periods. Higher percentages of consumers with a consumer lease or a SACC experienced two or more financial stress indicators, 28 per cent and 34 per cent respectively.

Chart 1 should be read with caution as while it shows that some BNPL consumers experience financial stress, the extent to which BNPL products contributes to this stress is unclear.

Furthermore, while Chart 1 shows that the level of financial stress associated with BNPL use is higher than the use of credit cards, such stress is significantly less prevalent than in other forms of credit such as consumer leases and SACCs, both of which are already heavily regulated. Recognising that the target market of BNPL products are younger people, it may be unreasonable to expect BNPL products to be associated with outcomes similar to credit cards whose customers are generally older.

16 per cent BNPL users surveyed missed a repayment in the previous year, while 43 per cent said they experienced difficulty in meeting BNPL repayment obligations in the previous year. In comparison, only 7 per cent of credit card users and 7 per cent of those with a mortgage missed repayments; and 14 per cent and 35 per cent said they experienced difficulty to make repayments, respectively. It should be noted that both cards and mortgages generally have significantly longer repayment periods (3 years and 20-30 years respectively), compared to many BNPL with 4-to-6-week repayment periods.

Users of multiple BNPL providers appear more likely to experience financial stress:

- •

- 14 per cent of one-provider BNPL users experience 2+ stress indicators;

- •

- 25 per cent of two-provider BNPL users experience 2+ stress indicators; and

- •

- 35 per cent of three-plus-provider BNPL users experience 2+ stress indicators.

2022 AFIA Industry Report: The Economic Impact of Buy Now, Pay Later in Australia

AFIA's report found 4.4 per cent of BNPL customers went without essentials to make payments and 7.3 per cent of customers cut back on essentials (11.7 per cent in total). [71] In contrast, AFIA's report found 5.1 per cent of credit card users went without essentials and 9.7 per cent cut back on essentials (14.8 per cent in total).

This data contrasts with ASIC's report 672 from 2020 that found that, in the prior 12 months, 20 per cent of BNPL consumer surveyed cut back on, or went without, essentials to make BNPL payments on time.

Consumers who held multiple BNPL accounts were more likely to cut back on, or go without, essentials or take out additional loans to repay BNPL on time. These surveys did not define what was essential and other studies have indicated that consumers may have a broad range of interpretations of the term. Younger respondents appear to interpret it as covering a wider range of expenditure than older respondents.

2020 ASIC Report 672: Buy Now, Pay Later: An Industry Update

ASIC report 672 found that 21 per cent of surveyed BNPL users missed a payment in the prior year. Among these consumers:

- •

- 34 per cent made at least six BNPL purchases in the prior 6 months; and

- •

- 55 per cent has used at least two different BNPL arrangements in prior 6 months.

ASIC report 672 also found that 15 per cent of BNPL consumers surveyed took out additional loans to make BNPL payments. The survey did not gather evidence that would determine whether this may have occurred in a non-problematic way.

One in five consumers surveyed, in the prior year, missed or were late paying other bills to repay BNPL. More than half of these (52 per cent) used at least two different BNPL products; and 29 per cent frequently used BNPL purchases (i.e., more than 6 purchases), in the prior 6 months.

ASIC report 672 also found that, of those surveyed, the percentage of buy now pay later transactions that incurred missed payment fees fluctuated between 9 per cent and 15 per cent each month from June 2016 to June 2019.

The issue of consumers incurring late fees may not be widespread.

Between October 2018 and January 2019, on average, 26 per cent more consumers who use both BNPL and credit cards incurred interest on their credit card balance than credit card users who did not use BNPL.

2018 ASIC report 600: Review of Buy Now, Pay Later Arrangements

ASIC report 600 found that one in six (16 per cent) of BNPL users experienced at least one type of negative impact from using BNPL, including becoming overdrawn, delaying bill payments, and borrowing money from family, friends or another loan provider to make repayments. However, less than 10 per cent of surveyed BNPL users were charged missed payment fees more than once on the same transaction in each quarter.

Of those who missed a payment, common reasons were:

- 1.

- forgot to put money in account (11 per cent);

- 2.

- needed to prioritise paying other bills (9 per cent); and

- 3.

- spent too much (5 per cent).

Bankruptcy and Debt Agreements

In unpublished analysis, the Australian Financial Security Authority found that while 34.2 per cent of all personal insolvencies had at least one BNPL debt, BNPL debts represented only 0.3 per cent of all unsecured debt in personal insolvencies in 2021. [72]

BNPL consumers can be charged excessive fees and charges

While BNPL providers are subject to a legislative fee cap in the Credit Act ($200 in the first year and $125 each year thereafter), the cap does not include late payment or default fees. It also does not cover merchant fees, which may be indirectly passed onto consumers through higher prices of goods and services.

Some stakeholders have raised that some BNPL providers charge disproportionate late fees compared to the value of the credit provided. However, many of the examples cited would also be permitted in relation to regulated credit and reflect borrowers using products with high fixed account fees for only very small amounts of credit. Some examples however reflect the impact of uncapped late fees.

For example, a consumer may be charged a $10 monthly account keeping fee on very low levels of outstanding BNPL debt, resulting in a high effective interest rate.

The current Code of Practice requires BNPL firms to cap their missed payment fees, but the level of the cap is not specified. As such, practices appear to be highly divergent within the industry, with some providers setting low caps and others higher caps, relative to debt size. Most BNPL accounts are with providers who currently cap their late fees to levels that are lower than other forms of regulated credit, including the legislated cap for SACCs.

Generally, not accounting for indirect impacts on prices of merchant fees, BNPL is a low-cost form of credit. It is difficult to assess its cost if you do account for possible indirect impacts of prices of goods and services arising from merchant fees.

Inadequate dispute resolution and hardship processes

Consumer groups have consistently raised concerns that BNPL providers have ineffective complaints handling processes to address disputes to a satisfactory standard and in a timely manner. This is despite the vast majority of BNPL accounts (approximately 90 per cent) are issued by providers who have committed to meeting ASIC's dispute resolution standards through AFIA's Code of Practice. However, consumer groups consistently and strongly assert that in practice BNPL firms are not meeting these standards. There are also concerns that not all BNPL providers are signatories of the AFIA Code of Practice.

Concerns regarding dispute resolution and hardship assistance appear to relate more to the enforceability and compliance with existing AFIA requirements than problems with the requirements themselves.

Consumer groups state it can be difficult to contact a provider to make a complaint or request hardship assistance as BNPL providers may not provide an option to communicate via telephone and rather direct consumers to a smartphone app or email.

Consumer groups have raised cases of BNPL providers failing to meet ASIC standards in resolving disputes and hardship applications within specified timeframes.

Others felt hardship assistance, where granted, provided inadequate assistance, such as merely delaying a customer's payment. This may however reflect concerns by these stakeholders with the outcomes of hardship processes in general.

Consumer Complaints

The level of consumer complaints against BNPL is low.

ASIC's Consumer Monitor found that the percentage of the surveyed population reporting an 'issue, concern or problem' with different credit products was 3 per cent for BNPL, 3 per cent for credit cards, 10 per cent for payday loans and 11 per cent for personal loans greater than $5,000.

AFIA reported that, between 1 July 2020 to 30 June 2021, AFCA received 767 BNPL complaints. This accounts for 0.01 per cent of 5.9 million BNPL accounts during that time. In comparison, AFCA received 9,902 credit card complaints, which accounts for 0.08 per cent of personal credit card accounts (12.6 million) during the same period.

The rate of complaints to AFCA in FY 2021-22 against BNPL firms per BNPL customers was 0.015 per cent. [73] However, some consumer groups consider that few consumers understand their rights to access external dispute resolution (EDR) as some BNPL providers fail to provide sufficient information to consumers on how to access AFCA. ASIC's most recent consumer monitor report for Q1 2022 suggests that on average, only 52 per cent of consumers knew they had a right to make a complaint to an EDR agency about a BNPL provider.

Most complaints against BNPL providers were readily conceded and settled. AFCA statistics indicate 68 to 75 per cent of complaints were unilaterally resolved by the firm, with an additional through 5-6 per cent resolved through negotiated settlement. This may reflect the commercial realities arising from the costs associated with firms defending complaints in relation to very small amounts.

Hardship requests

Similar to the level of consumer complaints, the number of hardship arrangements for BNPL products is very low.

AFIA's 2022 report found that as of 30 June 2021, only 0.34 per cent of BNPL customers applied for and were placed in hardship arrangements by BNPL providers. As of February 2022, one major BNPL provider reported that the number of hardship requests received per transacting customers was 0.05 per cent.

Hardship and complaints statistics must be read in light of concerns regarding the level of customer awareness of complaints and hardship processes, difficulties in navigating those processes and that many customers will not engage in such processes due to the average small size of debts and concerns that this may result in them losing access to BNPL.

Non-transparent fees and lack of understanding

BNPL is not subject to Credit Act disclosure obligations, including requirements for credit guides, warning statements and product disclosure statements. Equivalent commitments under the AFIA Code of Practice are less onerous and more principle based.

According to ASIC's most recent consumer monitor report for Q1 2022, nearly one third of BNPL consumer base do not understand the fees and charges for all of their BNPL arrangements.

Consumer groups assert that the varying fees across BNPL contracts are not transparent or easy to understand, and consumers cannot effectively compare fees across different products.

However, there are indications that even for providers with good disclosure practices there can be a lack of understanding of fee structures – indicating that the problem is also driven by consumer behavioural issues and lack of interest by some consumers in informing themselves about fee structures before taking out BNPL credit.

Equivalent data for non-BNPL credit products is also limited, hindering an understanding of the extent to which the lack of understanding is different for BNPL or is driven by BNPL specific factors.

Non-participation in credit reporting

Consumer groups and other lenders have raised issues around the lack of transparency of a person's level of BNPL indebtedness, particularly as many BNPL providers do not participate in credit reporting.

Consumer groups argue this enables vulnerable debtors to access multiple BNPL accounts even if they are currently in default, while some other lenders argue it impacts their ability to conduct affordability assessments.

Only the four largest banks are subject to mandatory credit reporting, with other credit providers reporting on a voluntary basis (although generally incentivised to do so under reciprocity principles set by credit reporting bodies). Other forms of regulated credit also appear to have low levels of credit reporting – such as SACCs and consumer leases.

Only a few BNPL providers voluntarily report to credit reporting agencies.

Some others conduct credit checks, which may leave a record visible through credit checks that applications for BNPL had been made by a consumer (but not the outcome of those applications).

Some stakeholders indicated that access to banking transaction data (through the consumer data right or digital data capture) enables BNPL and other credit providers to detect the presence of other BNPL accounts, albeit with an imperfect understanding of the use and credit limits for those accounts.

Inappropriate advertising

BNPL is not subject to some restrictions on misleading advertising (although some ASIC Act consumer provisions and the Australian consumer laws do apply) or to restrictions on harassing marketing.

Inappropriate advertising has been raised as encouraging consumers to use BNPL for essentials, such as utility firms prominently displaying BNPL as a method for paying bills.

It is unclear how much this causes harm when it does not induce unaffordable lending. For example, it is extremely common for households to purchase groceries using credit cards and yet similar concerns are not being actively raised regarding these practices.

Consumer groups also argued advertising BNPL products for essentials, such as utility bills, steers struggling consumers away from hardship support that utility companies are legally required to offer.

Competitive neutrality

A number of regulated credit providers and consumer groups have raised concerns that BNPL firms are engaging in regulatory arbitrage, arguing principles of competitive neutrality support equal regulations.

While some BNPL products are similar to regulated products (e.g., credit cards including cards with repayments with similar instalment plans), others have no equivalents. Some BNPL products have emerged that are even closer to credit cards from a user perspective than most BNPL products (e.g., open system BNPL utilising card payment systems).

Stakeholders have also raised issues with BNPL regulation as a payments system – in particular how it is not subject to surcharging regulation in contrast to credit cards. These issues are better addressed by the response to the Payments System Review which is currently being considered by the Government.

2. Why is Government action needed?

Vulnerable consumers need effective consumer protection

Stakeholder consultations, surveys and other quantitative data and analysis indicate that some consumers are experiencing harm from taking on too much debt that they cannot repay, as well as other issues such as a lack of appropriate dispute resolution mechanisms, hardship assistance and non-transparent fees. Harms from unaffordable lending are particularly concentrated among lowincome borrowers, social security recipients, and other vulnerable cohorts, as well as those also utilising multiple BNPL accounts or SACCs and consumer leases.

Attempts by industry to self-regulate have been only partially effective in addressing these concerns due to incomplete coverage of the Code of Practice, a lack of rigour in some industry commitments, insufficient compliance by some providers with those commitments and a lack of mechanisms to penalise or exclude bad actors.

Industry self-regulation has also resulted in an uneven playing field between BNPL and functionally equivalent regulated credit products, such as credit cards.

This supports a case for implementing credit regulation upon BNPL, albeit in a manner that is flexible and technologically neutral and in a way that imposes key requirements in a proportionate way that scales with the risks of consumer harm associated with the product.

Demonstrate that government has the capacity to intervene successfully.

The proposed reforms would implement existing credit regulation (albeit in a modified form), to be administered by ASIC, which currently regulates consumer credit.

The proposed regulated population is small. There are currently only 15 BNPL providers, and this is expected to decrease as industry consolidates naturally, even without regulatory intervention, given the commercial pressures BNPL providers are experiencing, including from the rising cost of capital.

Identify alternatives to government action.

Currently, BNPL products are not regulated under the Credit Act. The alternative to government action in this instance is to either maintain the status quo or seek to enhance the AFIA BNPL Code of Practice.

- •

- Maintaining the Status Quo: This would involve acceptance of current levels of consumer harm and a lack of competitive neutrality between some credit products. As discussed above, the Government's consultation has determined that unaffordable lending is leading to significant financial stress among some vulnerable consumers, which would persist under the status quo.

- •

- Enhancing the BNPL Code of Practice: Encouraging the industry to improve its Code of Practice may, depending on the commitments made, marginally improve consumer protection for BNPL consumers. However, the Code of Practice would continue to not have full coverage of the industry with more problematic providers not willing to voluntarily

become Code signatories. Compliance concerns may be partially alleviated through more rigorous action by Code compliance mechanisms, however there would be no ability to impose civil penalties or exclude bad actors from the industry (as opposed to expelling them from the voluntary industry body).

These are set out in further detail below under Options for Reform.

Clearly identify what objectives or outcomes you are aiming for

Our objective is to address risks of unacceptable levels of consumer harm, such as unaffordable lending, that may arise from the use of BNPL. The harms being targeted are outlined above in the problem identification. These risks should be addressed in a proportionate way that, as far as is possible, targets the industry practices that give rise to these risks.

The reforms also seek to address the harms that may indirectly flow to persons who are not decision makers in BNPL transactions. These negative externalities include the negative financial and social impacts upon the families of BNPL borrowers.

Australian consumers, merchants and the economy have benefited from the rise of the BNPL industry, and it is important to ensure that any frameworks aimed at addressing risks of consumer harms do not unduly come at the expense of these benefits.

Reforms should target levels of risk to consumers that are lower than those that are optimum for maximising profitability of firms (which may result from reliance on market forces and would be expected not to take into account negative externalities, such as impacts of unaffordable lending upon borrowers' families). Reforms are not aiming to reduce risks to nil, given that this is likely to unacceptably harm financial inclusion benefits of BNPL and other benefits to consumers, merchants and the economy.

Treasury has used the consultation process to develop the following guiding principles to inform the options outlined below for a new regulatory framework for BNPL. These principles have been publicly consulted upon with stakeholders:

- -

- improve consumer protections by addressing the main instances of consumer harm arising from BNPL products while continuing to ensure BNPL products are accessible to consumers.

- -

- be flexible enough to allow new BNPL providers into the market and for new and existing BNPL providers to bring new financial products onto the market.

- -

- respect the competitive nature of the market and the roles and interests of consumers, merchants, and providers in the BNPL sector.

- -

- consider the existing regulatory arrangements for comparable regulated credit products, such as credit cards, SACCs, consumer leases, and other types of personal loans.

- -

- be practicably enforceable by a regulator such as ASIC in a cost effective and efficient way that minimises the risk of avoidance behaviour.

Identify the constraints or barriers to achieving your goal.

Uncertainty in the extent and nature of the problem

There is a lack of granular data on who is suffering harm, the extent and nature of the harms, and the causes of those harms. There are inconsistencies in available quantitative data and between that data and anecdotal observations made by stakeholders. This can create challenges in ensuring laws appropriately target actual harms, in a proportionate manner, without imposing unnecessary regulatory burdens on non-problematic activities.

A lack of data may also pose challenges to post implementation assessment of the effectiveness of reforms.

Tensions between targeted and consistent regulation

A key challenge in ensuring that any response is tailored and focussed on identified harms associated with BNPL, without creating excessive inconsistency and complexity within credit product regulation. This is particularly a challenge in relation to tailoring RLOs so that they scale with risk.

Tensions between flexibility and certainty in regulation

A key challenge is ensuring that BNPL regulation allows the industry to continue to innovate in relation to product and business model design, while still providing sufficient certainty for industry, enforceability by ASIC and not creating opportunities for avoidance activity.

One aspect of this is ensuring clarity to providers and regulators as to what is proportionate and reasonable risk mitigation in relation to affordability assessments.

Ensuring regulation is effective but also efficient

A key challenge, in relation to regulation that scales with risk, is to ensure frameworks minimise regulatory burdens upon providers while remaining effective to mitigate risks.

Minimising negative impacts upon consumer experiences and timeliness of processes is especially important to avoid undue negative impacts on BNPL business models. That said, some positive frictions in consumer experiences may help minimise consumer harms.

Minimising negative unintended consequences

Another challenge is to ensure that BNPL is made safer without imposing undue inconveniences and costs on consumers that may then drive them to less safe or more expensive credit products. The Government's consultation heard feedback from some vulnerable consumers, such as pensioners, suggesting that excessive regulation may reduce their access to lower cost BNPL products, which would harm financial inclusion.

Legislation

Legislation will be required to implement the preferred option.

Uncertainty as to scope

Reforms will need to clearly set out an appropriate scope for their application. For example, a key challenge is defining what should be considered to be BNPL for regulatory purposes. There are arguments for and against this scope being consistent with the scope of other BNPL related reforms (such as payment regulation or the application of the Consumer Data Right to non-bank lenders).

What is BNPL is still not settled. BNPL is a relatively new and innovative product. There is a still changing range of products with varying features that may be considered to be BNPL.

Adopting an overly broad definition will have higher risks of other products for which there is not an established case for regulatory intervention, such as invoice financing, being unintentionally captured.

Ensure your objectives are: specific, measurable, accountable, realistic, and timely.

The Government has announced that it is proposing that legislative reforms will be introduced into parliament in late 2023.

Implementation details have yet to be settled, however it is likely that laws would commence after a reasonable delay after passage of legislation and making of supporting regulations.

The success of the reforms could be measured primarily through:

- •

- observing changes in statistics on financial stress measures, complaints, changed spending behaviours on essentials, late payment rates and published bad debt provisions by firms.

- -

- For example, a reduction in the percentage of 2+ HILDA financial stress indicators from their current level of 19% and a reduction in number of BNPL consumers who had missed a repayment in the last year from 16% is expected.

- -

- Observations would be compared against those for other credit products that are either functionally similar (e.g. credit cards), fulfil similar needs or are accessed by similar customer cohorts (e.g. small amount credit contracts). However, recognising that the target market of BNPL products are younger people (who are, as a whole, a higher-risk cohort), it may be unreasonable to expect BNPL products to be associated with outcomes similar to credit cards whose customers are generally older.

- •

- seeking feedback from financial counsellors on the incidents of consumer harm that they are observing; and

- •

- analysis of enhanced complaint handling statistics (that would be gathered once BNPL providers are licenced and subject to reporting obligations).

3. What policy options are you considering?

The following options were consulted upon as part of the Treasury options paper Regulating Buy Now, Pay Later in Australia (November 2022).

3.1 — Maintain the status quo

The status quo is described in the section on 'Background' above. In summary, while BNPL products are exempt from certain consumer protections in the Credit Act, such as the RLOs, they do exist within the broader regulatory framework covering financial products. This includes the ASIC Act's general financial services consumer protections, the Design and Distribution Obligations and Product Intervention Powers provisions, the Australian Consumer Law, and the Anti-money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Act. The AFIA Code of Practice further provides protections to consumers who contract with a BNPL firm that has signed up to the Code. This includes commitments around dispute resolution and hardship, conducting tiered suitability tests, chargeback and refund requirements, financial abuse, advertising and marketing, and adhering to consumer communication requirements.

Maintaining the status quo would not address the level of unaffordable lending that is currently occurring and would not address the variety of other concerns with BNPL providers such as those relating to internal dispute resolution, hardship provisions, disclosure and marketing rules, among others.

3.2 Option 1 – Stronger BNPL Code of Practice with affordability test

Option 1 proposed a government-industry co-regulation regime, where the current AFIA BNPL Code of Practice is strengthened to address current gaps in coverage, supplemented with a bespoke affordability test legislated under the Credit Act.

The Credit Act would be amended to impose BNPL specific requirements on providers to check that a BNPL product is not unaffordable for a person before offering it to them. This requirement would seek to address the primary issue of unaffordable lending in a tailored manner. The affordability test would be a bespoke regime, with a different framework to the RLOs. The bespoke provisions would provide for the scalable and efficient checking of a consumer's ability to afford the BNPL credit related to the overall value of the credit being provided.

There would be no requirement for BNPL providers to obtain and maintain an ACL.

The BNPL industry would work in consultation with government to strengthen various provisions in the Code of Practice to ensure higher standards for BNPL providers. The strengthening of the Code would seek to address any further concerns (in addition to existing commitments) relating to:

- -

- product disclosure and warning disclosure requirements;

- -

- access and standards of dispute resolution and hardship practices;

- -

- excessive consumer fees and charges, including default fees;

- -

- refund and chargeback processes;

- -

- advertising and marketing;

- -

- mitigating risks associated with scams, domestic violence, coercive control, and financial abuse; and

- -

- ensuring its compliance of these requirements are adequate.

Certain provisions in the improved Code of Practice could be enforceable by ASIC, subject to the industry body's application and ASIC's approval. The Code could also be mandated for all BNPL providers, however participation in the credit reporting framework would continue to be voluntary. This may not adequately address issues regarding enforceability and coverage of the industry, as the more problematic providers would likely continue not to sign up to the Code.

The revised Code would supplement but not override the bespoke affordability checks that would be specified in the Credit Act.

ASIC would be able to issue regulatory guidance on the interpretation of the statutory obligations.

3.3 Option 2 – Regulation under the Credit Act with scalable unsuitability tests

This option proposes to bring BNPL within the Credit Act's application to apply a tailored version of the RLOs to BNPL products. This option seeks to address the key issue of unaffordable lending by applying the RLO framework which ensures that providers do not provide consumers with loans that are unsuitable for them, but in a way that allows for the RLO assessment to be scaled-down according to the risk of the product.

Key features of the proposal include amending the Credit Act to require BNPL providers to hold an ACL, or be a representative of a licensee, with a requirement to comply with most general obligations of a licensee, including:

- -

- Internal and external dispute resolution, hardship provisions, compensation arrangements, fee caps and marketing rules.

- -

- The provisions could be calibrated to the level of risk of BNPL products and services. This could include exemptions from reference checking, and other obligations that do not relate to issues identified in the BNPL business practices.

This option would not require merchants who offer BNPL products to consumers to be an authorised credit representative of the BNPL provider.

As a licensee, BNPL providers will be able to engage more meaningfully with the existing credit reporting regime under the Privacy Act 1988 (Privacy Act), including repayment history information and hardship information in accordance with the Principles of Reciprocity and Data Exchange. Participation in the comprehensive credit reporting framework would continue to be voluntary unless the provider is a big bank.

BNPL providers would be required to assess that a BNPL credit is not unsuitable for a person, similar to the existing RLO framework, scaled to the level of risk of the BNPL product or service. This may include removing some prescriptive requirements, such as verifying a person's financial documentation and checking that the BNPL credit aligns with the person's needs and objectives. BNPL providers would be required, at a minimum, to collect financial information and use that information and any other statistical data (such as credit scores) to ensure that BNPL is not unsuitable for a person.

BNPL providers would be prohibited from increasing a consumer's spending limit without explicit instructions from the consumer.

Fee caps for charges relating to missed or late payments would be required, combined with additional warning and disclosure requirements.

These legislative amendments could be supplemented by the strengthened Code of Practice similar to that as described in Option 1 for those issues not dealt with by the legislation.

The options would still exist for AFIA to apply to have parts of the Code enforceable by ASIC.

Under this option amendments would be required to ensure credit regulatory frameworks apply to BNPL business models in a sufficiently flexible and technologically neutral way, and that aspects of credit licencing with little to no relevance to the direct-to-consumer online business channels of most BNPL did not apply.

This option would not require merchants who offer BNPL products to consumers to be an authorised credit representative of the BNPL provider.

3.4 Option 3 – Regulation of BNPL under the Credit Act

This option would treat BNPL products identically to other credit products regulated under the Credit Act and require BNPL providers to comply with regulations in an unmodified form, such as the RLOs. This would seek to address the key issue of unaffordable lending by requiring providers to conduct the same kind of unsuitability assessment as all other regulated credit providers.

Accordingly, BNPL providers would be required to hold an ACL or be an authorised representative of one. BNPL providers would be required to check and satisfy themselves that a BNPL is not unsuitable for a person in accordance with RLOs.

As a licensee, BNPL providers would need to comply with all licensee obligations, including the reportable situations regime, internal and external dispute resolution, compensation arrangements, ASIC reporting obligations, as well as Credit Act requirements including information sharing, warnings, and hardship provisions. This option is not expected to require merchants who offer BNPL products to be an authorised credit representative.

It is proposed that there be an additional requirement that BNPL providers would need to allow consumers to set their own spending limits and prohibited from increasing a consumer's spending limit without their permission. A more restrictive requirement of this kind applies existing continuing credit contracts.

Fee caps for charges relating to missed or late payments would be applied, combined with disclosure requirements.

BNPL providers would be better able to engage with the credit reporting regime to share and receive all credit information, including repayment history information and hardship information because they would be licensees. BNPL providers would not be captured under the mandatory CCR regime unless the BNPL provider is a big bank.

A revised AFIA Code of Practice could include provisions to address issues not appropriately considered within the scope of the Credit Act, including setting industry standards, refund and chargeback processes, and providing guidance to BNPL providers on identifying situations of domestic violence, coercive control and financial abuse. The industry could also choose to further strengthen its Code to ASIC's approved standard and set a higher industry standard than required by law.

4. What is the likely net benefit of each option?

4.1 Status quo

The status quo, including statistics on its harms and benefits, is described in the section on 'Background' above. In summary, BNPL has produced benefits to consumers, in the form of accessible and relatively low-cost credit, merchants, in the form of increased sales and customer acquisition, and the economy at large, through increasing competition against regulated credit products such as credit cards and small amount credit contracts.

Nevertheless, the Government's consultation found that, under the current regulatory environment (status quo) for BNPL, there are problems in relation to unaffordable lending, as well as poor hardship and dispute resolution practices of some BNPL providers. To a lesser degree, there are indications that problems also exist in some cases in relation to BNPL with excessive fees, product disclosure, transparency of indebtedness and competitive neutrality. This is described further in Section 1 'What is the problem you are trying to solve?'.

As such, while the rise of BNPL has created significant benefits to consumers, merchants and the economy, it has also led to some vulnerable consumers (such as social security recipients with low incomes) experiencing significant financial stress from being extended credit they cannot afford, as well as lacking avenues to raises disputes and hardship requests with providers.

The status quo would therefore provide the most benefit to providers and merchants and the most harm to consumers.

4.2 Option 1 – Stronger BNPL Code of Practice with affordability test

Option 1 retains the existing piecemeal regulatory framework for BNPL arrangements, where BNPL providers are not required to comply with the responsible lending obligations under the Credit Act or hold an Australian Credit Licence. Key consumer protections would not be subject to enforcement by a regulator, likely perpetuating current concerns regarding compliance and the ability to penalise or exclude bad actors.

Option 1 would likely deliver a slight net benefit over the status quo. However, much of the existing levels of consumer harm would persist. Introducing a bespoke affordability test would raise the level of creditworthiness assessment that providers must undertake when looking to extend credit to a consumer. For example, depending on the kind of BNPL that is being provided (including the value, term and target market of the BNPL product), providers may need to check the person's credit score and assess their level of income. Given that this proposal does not leverage the existing RLO regime, there is uncertainty as to how any bespoke regime might work and how effective it might be.

On balance, this would deliver a minor level of benefit over the status quo because it would only marginally reduce the level of unaffordable lending while raising annual regulatory costs by an estimated $7.95 million for consumers, BNPL providers and merchants (described below).

Given the bespoke affordability test falls short of the more stringent RLO regime, the test will likely prove to be only marginally effective in prohibiting unaffordable lending of BNPL products to vulnerable consumers. Moreover, a specialised regime outside of the RLO framework would also add further complexity to laws and would not alleviate competitive neutrality concerns because similar credit products would continue to be regulated under different regulatory frameworks.

Option 1 also proposes that industry would be given the opportunity to strengthen its Code of Practice with regard to product disclosure and warning requirements, access and standards of dispute resolution and hardship, the charging of default fees, refund and chargeback processes, advertising and marketing, and mitigating risks associated with scams, domestic violence, coercive control, and financial abuse. The current Code of Practice addresses all these issues, with some commitments not being sufficiently strong but others apparently failing to deliver sufficiently good outcomes due to compliance and enforcement deficiencies (some of which may arise from the inherent limitations of industry codes). Because the changes would be industry-led, rather than being designed by government and enforced by government regulators, it is not possible at this stage to quantify the marginal cost to industry and benefit to consumers. Nevertheless, allowing industry to strengthen the Code (rather than addressing concerns through legislating under the Credit Act) is anticipated to lead to a negligible increase in compliance costs. It would also lead to a limited and marginal improvement in consumer protection above the status quo, as providers would be strengthening the provisions in a voluntary industry Code of Practice that not all BNPL providers are a signatory to.

This option would therefore have the most benefit (of the options for reform) to providers and merchants and the most harms to consumers.

Regulatory burden estimate (RBE) table

BNPL providers: Under Option 1, BNPL providers can be expected to incur relatively minor compliance costs of around $3.3 million a year comprising of predominantly administrative costs associated with carrying out additional suitability assessments. Under Option 1, it is expected that BNPL providers would largely continue to use their existing systems and would not have to build significant new Information Technology to comply. This costing does not incorporate an estimate of a loss of profits due to loss of clients as it is unclear whether any firms are currently profitable and when (and to what extent) profitability is expected to occur.

A new, bespoke suitability assessment may include, for example, conducting negative credit checks, which are expected to cost around $1 per check conducted, on average. It may also lead to a reduction in lending as the bespoke suitability test would exclude certain consumers who cannot afford the credit.

For certain consumers who have poor credit scores, providers may need to conduct additional assessments on top of this, such as requiring a BNPL provider to consider additional financial information (such as their income).

Merchants: Merchants accepting BNPL can be expected to incur costs from lost profits of around $278,000 per annum from lost new customers as a result of regulation. It is also expected that BNPL providers will pass a proportion of its regulatory cost onto merchants through higher merchant fees charged by BNPL providers.

Individuals: Individual BNPL users can expect to incur a cost of around $396,000 a year arising from the additional time users are likely to take to satisfy any additional regulatory checks when applying for BNPL.

Community organisation: Nil, the proposed regulation under Option 1 does not impact community organisations.

| Average annual regulatory costs | ||||

| Change in costs ($ million) | Individuals | Business | Community organisations | Total change in cost |

| Total, by sector | $0.40 | $3.56 | Nil | $3.96 |

4.3 Option 2 – Regulation under the Credit Act with scalable unsuitability tests

Option 2 requires BNPL providers to hold an Australian Credit Licence, comply with licensing obligations, and ensure a BNPL product is not unsuitable for the person under a modified RLO framework that scales down according to the risk of the product. Licensing also enables ASIC to better monitor and regulate BNPL providers in full.

Option 2 is anticipated to deliver a significant net benefit to consumers.

Compared to the status quo, consumers will benefit through improved consumer protection that reduces the instances of unaffordable lending. It is anticipated that the modified RLO regime will reduce the level of 2+ HILDA financial stress indicators from their current level of 19 per cent to be more closely

(but not exactly) in line with other regulated credit products such as credit cards. Similarly, it is anticipated that the level of consumers who miss a BNPL repayment per year will reduce from the current level of 16 per cent to be closer to that of credit card consumers (only 7 per cent of credit card users missed repayments in the previous year). It should be noted that credit cards have longer repayment periods (typically 3 years), compared to many BNPL products with 4-to-6-week repayment periods. Moreover, the typical BNPL consumer is younger than a typical credit card holder, which may indicate a higher risk cohort. As such, it is not expected that the level of financial stress and missed repayments for BNPL consumers would be the same as credit card consumers.

The modified RLO regime may also lead to some consumers who currently have access to BNPL losing that access, either because the increase in regulation makes it uneconomical for BNPL providers to provide credit to them or because the modified RLO regime obligations will determine that they cannot afford the credit. This may reduce the financial inclusion benefits of BNPL as well as its competitive effect upon other traditional credit products such as credit cards and small amount credit contracts. A case study is provided below of how the modified RLO regime may restrict access to BNPL credit for consumes who cannot afford it.

Compared to the status quo, BNPL providers will suffer a detriment through the cost of holding an Australian Credit Licence and being subject to other Credit Act requirements. Out of the 15 BNPL providers that currently exist in the market, eight of them hold an Australian Credit Licence. It is anticipated that seven BNPL providers will have to acquire and maintain a licence, while the other eight providers will need to vary their existing licences. ASIC's licence application fees for credit providers are $4,624, whereas application fees for varying a licence is $2,826. This creates a one-off total cost of $54,976. Costings also incorporates estimates of the legal and administrative costs with applying for or varying licences.

Further, compared to the status quo, a modified RLO regime will increase the level of administrative compliance costs (discussed further below). However, the proposed modified RLO regime is more flexible and less costly to comply with than the current RLO regime under the Credit Act. Option 2 maintains the principle based RLO framework to ensure BNPL is not provided to those whom it is unsuitable, but ensures that the RLO assessment that providers must undertake scales down according to the risk of the product. The kind of assessment that a provider will be required to undertake will depend on many factors such as the size of the loan, its fee and repayment structure, the product's target market, any risk management features of the provider (such as whether a customer's account is frozen after a missed payment), and whether or not providers enforce the collection of debts. An example of how a scalable RLO may work for a $800 pay-in-four product is provided below.

Case Study

Nigel is a full-time student receiving fortnightly youth allowance. Nigel is a renter and does not hold any other credit product. Over the last few months, he has missed paying his rent and paying a number of utility bills.

Nigel applies for an $800 pay-in-four BNPL account with 'PayInstall' using his mobile device. Following the implementation of the reforms, PayInstall must ensure that the BNPL account is not unsuitable for Nigel. That said, because PayInstall is a low-cost credit contract, PayInstall would only be required to check summaries of Nigel's financial situation and any statistical data (such as a credit score) when assessing suitability.

Nigel is asked to provide some information about his financial situation to PayInstall, including consenting to PayInstall conducting a negative check on Nigel's credit file. PayInstall must use the information provided to decide whether the BNPL is suitable for Nigel.

While Nigel has some level of income (Youth Allowance), he is rejected for the BNPL because he has missed, or was late, paying rent and utility bills.

Under the proposed reform, BNPL providers cannot lend to those who the BNPL product is unsuitable. BNPL providers are required to consider the risk profile of its product (including the value of the BNPL account, length of the term, size of the fees, the target market of the product, and any harm mitigation measures), to determine the level of assessment it must do under the modified RLO regime.

Under a new modified RLOs and credit licence obligations BNPL providers may be required to in the first instance check the person's suitability for BNPL against a statistical data (such as a credit score), and where further assessment is required, collect, and consider a person's financial circumstances to ensure they do not extend credit to those who the credit is unsuitable. Option 2 also requires BNPL providers to have appropriate information technology systems in place to achieve this and ensure personal information is collected and stored in a secure way. Additionally, under Option 2 BNPL providers would incur compliance costs associated with either applying for an Australian Credit Licence or modifying their authority under an existing licence, and to appropriately train their staff.

This option would therefore have moderate negative impacts upon providers and merchants and the most benefits to consumers (taking into account both harm reduction and maintaining consumer benefits from access to BNPL).

Regulatory burden estimate (RBE) table

BNPL providers: Under Option 2, BNPL providers can be expected to incur compliance costs of around $9.5 million a year comprising of substantive compliance costs associated with developing or purchasing appropriate information technology system, training staff, legal matters, administrative costs associated with carrying out additional suitability assessments, and, for some BNPL providers, costs associated with obtaining a credit licence (and for others the costs of varying existing licences) and becoming a member of AFCA. This costing does not incorporate an estimate of a loss of profits due to loss of clients as it is unclear whether any firms are currently profitable and when (and to what extent) profitability is expected to occur.

Merchants: Merchants accepting BNPL can be expected to incur costs from lost profits of around $1.4 million from lost new customers as a result of regulation. No significant increase in administrative burden is expected to impact merchants. It is also expected that BNPL providers will pass a proportion of its regulatory cost onto merchants through higher merchant fees charged by BNPL providers (increasing the net impact upon merchants and reducing the net impact upon BNPL providers).

Individuals: Individual BNPL users can expect to incur a cost of around $4.09 million a year arising from the additional time users are likely to take to satisfy additional regulatory checks when applying for BNPL.

Community organisation: Nil. The proposed regulation under Option 2 does not directly impact community organisations.

| Average annual regulatory costs | ||||

| Change in costs ($ million) | Individuals | Business | Community

organisations |

Total change in cost |

| Total, by sector | $4.09 | $10.91 | Nil | $15.00 |

4.4 Option 3 – Regulation of BNPL under the Credit Act

Option 3 would apply the existing Credit Act regulations in full to BNPL arrangements. This includes requiring BNPL providers to obtain an Australian Credit Licence and comply with the RLO framework, without any modifications.

Under the existing RLO framework and credit licence obligations BNPL providers are required to collect and consider a person's financial information, verify the financial information, and check against the person's requirements and objectives to ensure they do not extend credit to those who the credit is unsuitable. The kind of financial information that may need to be collected and verified under RLOs is potentially extensive – including conducting a credit check, obtaining verified financial statements, assessing the kind and source of income and whether it is seasonal or otherwise irregular, as well as considering a person's expenses and determining what are discretionary and non-discretionary. Option 3 also requires BNPL providers to have appropriate Information Technology systems in place to achieve this and ensure personal information is collected and stored in a secure way. Additionally, under Option 3 BNPL providers would incur compliance costs associated with either applying for an Australian Credit Licence or modifying their authority under an existing licence, and to appropriately train their staff. As mentioned above, of the 15 BNPL providers that currently exist in the market, eight of them hold an Australian Credit Licence. Recently, three BNPL providers (OpenPay, Affirm and Latitude) have left or are leaving the Australian market, or become subject to formal reorganisation processes. Seven BNPL providers will have to acquire and maintain a licence, while the other eight providers will need to vary their existing licences. ASIC's licence application fees for credit providers are $4,624, whereas application fees for varying a licence is $2,826. This creates a one-off total cost of $54,976. Costings also incorporates estimates of the legal and administrative costs with applying for or varying licences.

Compared to the status quo, the cost of regulation would reduce innovation in the financial system and the growth of the sector. It may also lead to providers exiting the market or merging with other providers due to their business model being made uneconomical. Wholesale RLO assessments may prove to be too expensive and time consuming to conduct for small-value, low-cost credit. Currently, many BNPL product offerings include automated decision making, with decisions on whether to extend credit to consumer made very quickly. The Government heard through its consultation with industry that, compared to this status quo, Option 3 would slow down the decision-making time substantially, requiring providers to collect and verify information and potentially ask further questions of applicants. It would also raise the cost of extending credit, which may lead to some lower-value BNPL products (with low margins) being made uneconomical.

Compared to the status quo, consumers will marginally benefit from a wholesale application of existing Credit Act regulation, whereas BNPL providers and merchants will see significant detriment to their businesses. It is anticipated that applying the existing RLOs wholesale to all BNPL arrangements would prevent BNPL providers from extending credit to those who it is unsuitable. This will benefit consumers through improved consumer protection that reduces the instances of unaffordable lending. It is anticipated that the modified RLO regime will reduce the level of 2+ HILDA financial stress indicators from their current level of 19 per cent to be more closely in line with other regulated credit products such as credit cards (where only 8 per cent of consumers experience 2+ HILDA financial stress indicators).

However, Option 3 would also cause significant detriment to the user experience of a great majority of consumers who enjoys the benefits of BNPL, as a result of undue information gathering and delays in accessing BNPL. One of the benefits of BNPL products is the ease of user experience and its broad availability. Option 3 is anticipated to significantly slow down the provision of BNPL products and restrict access to many BNPL consumers due to small-value low-cost BNPL products being made uneconomical. This would harm consumers due to a loss of financial access. Excessive barriers to accessing generally low cost BNPL may also result in some consumers accessing higher cost alternatives.

This option would therefore have the greatest negative impacts upon providers and merchants and less benefits to consumers that option 2. While harm reduction to consumers would be maximised under this option, this would come at the expense of decreased consumer benefits from access to BNPL.

Regulatory burden estimate (RBE) table

BNPL providers: Under Option 3, BNPL providers can be expected to incur compliance costs of around $22.1 million a year comprising of substantive compliance costs associated with developing or purchasing appropriate information technology system, training staff, legal matters, administrative costs associated with carrying out additional suitability assessments, and, for some BNPL providers, costs associated with obtaining a credit licence (and for others the costs of varying existing licences) and becoming a member of AFCA. Compliance cost under Option 3 is expected to be significantly greater than under Option 2, as all new BNPL applications would need to undergo detailed suitability assessment, including assessing a person's income and expenses and verifying those information. It is expected that BNPL providers, under Option 3, will take twice as long to manually assess all new applications, whereas Option 2 can rely on a higher degree of automation. This costing does not incorporate an estimate of a loss of profits due to loss of clients as it is unclear whether any firms are currently profitable and when (and to what extent) profitability is expected to occur.

Merchants: Merchants accepting BNPL can be expected to incur costs from lost profit of around $1.4 million from lost new customers as a result of regulation. No significant increase in administrative burden is expected to impact merchants. It is also expected that BNPL providers will pass a proportion of its regulatory cost onto merchants through higher merchant fees charged by BNPL providers.

Individuals: Individual BNPL users can expect to incur a cost of around $9.9 million a year arising from the additional time users are likely to take to gather personal financial information and satisfy any other regulatory checks when applying for BNPL.

Community organisation: Nil, the proposed regulation under Option 3 does not impact community organisations.

| Average annual regulatory costs | ||||

| Change in costs ($ million) | Individuals | Business | Community organisations | Total change in cost |

| Total, by sector | $9.90 | $26.17 | Nil | $36.07 |

| Average annual regulatory costs | ||||

| Change in costs ($ million) | Individuals | Business | Community organisations | Total change in cost |

| Total, by sector | $9.90 | $23.53 | Nil | $33.43 |

5. Who did you consult and how did you incorporate their feedback?

Consultation Process

The proposed legislative reforms of BNPL products are the result of extensive consultation with consumer groups, industry, academia, regulators and foreign governments.

In 2018 and 2020, ASIC released two research reports, respectively, on the BNPL market. These reports together identified the rapid growth of the sector, the wide variety of BNPL products on the market, and that some consumers were experiencing financial harm from unaffordable lending, such as cutting back on essentials or being late on paying other bills to make BNPL repayments.

Following the Government's announcement of its intention to regulate BNPL in July 2022, Treasury held bilateral meetings with 28 stakeholders to identify, and understand the extent of, the issues with BNPL products.

The 28 bilateral consultations informed the development of three options of varying degrees of regulatory intervention. The Options Paper, titled "Regulating Buy Now, Pay Later in Australia", summarised the issues with BNPL products and regulation and asked for public feedback on three options for regulatory intervention. The consultation ran from 21 November 2022 to 23 December 2022. The Government received 77 written submissions, 62 of which were non-confidential. Appendix A provides a list of stakeholders who provided a non-confidential submission.

Treasury held three roundtable sessions during the public consultation period with consumer groups, BNPL providers and the large banks to discuss the Options Paper and the three proposed regulatory options.

Following the close of the public consultation, Treasury has further held numerous bilateral meetings with consumer groups, BNPL providers and academics. Treasury has met with ASIC on a semi-regular basis since July to discuss an appropriate regulatory solution.

Common Issues Raised by Stakeholders

Unaffordable or Inappropriate BNPL Lending

The most commonly raised concern in submissions was unaffordable or inappropriate lending practices. Many of the submissions supported the paper's observation that some consumers are provided BNPL which they cannot afford or that is otherwise inappropriate for them.