Review of Business Taxation

A Tax System RedesignedMore certain, equitable and durable

Report July 1999

SECTION 11 - IMPUTATION AND THE COMPANY TAX RATE

| Achieving integrity through the entity chain |

| Simplification of the franking account |

| Refunding excess imputation credits |

| A common start date for entity taxation |

| Reducing the company tax rate |

Achieving integrity through the entity chain

Recommendation 11.1 - Unfranked distributions between resident entities

| That unfranked distributions (other than distributions within a consolidated group) between resident entities (including trusts and companies) be taxed in the recipient entity's hands. |

In A Platform for Consultation - see Overview (page 54) and Chapter 15 (pages 349-355) - the Review canvassed three options for treating entity distributions so as to achieve integrity through the entity chain. The three options were to:

- •

- impose a deferred company tax;

- •

- apply a resident dividend withholding tax; or

- •

- tax unfranked inter-entity distributions.

Each option would help address the unintended loopholes created by the way the existing section 46 rebate frees from tax most unfranked dividends between entities as well as the added complexity of the wide range of associated and other specific anti-avoidance provisions relating to the availability of the section 46 rebate.

Distributions between entities within a consolidated group would not be affected by any of the options. Under the consolidation regime (see Section 15) all intra-group distributions will be ignored for tax purposes.

Despite simplicity and compliance advantages, the main problems with the deferred company tax would be the adverse impact on reported after-tax profits of the distributing entity and the impact on non-portfolio distributions to foreign investors. While the proposed accompanying company tax/dividend withholding tax (DWT) 'switch' would generally have improved the position of portfolio investors under deferred company tax, consultations suggested that credits for deferred company tax relating to non-portfolio investors may only add to excess foreign tax credits. In addition there is uncertainty about acceptance of the switch by foreign jurisdictions.

Resident dividend withholding tax and taxing unfranked inter-entity distributions are similar to each other in that they would have no impact on reported after-tax profits of the entity making unfranked distributions. They would also have similar effect through the entity chain in that they impose tax on the entity that receives an unfranked distribution (although the impact may be different where the member's investment is geared - that is, when taxing unfranked inter-entity distributions, no tax will be paid if there are sufficient deductions to offset the distribution, yet under the resident dividend withholding tax, the tax will have already been withheld). Both options would also apply a non-resident DWT ? generally at a 15 per cent rate ? to unfranked distributions paid directly to foreign investors, consistent with the existing law and Australia's tax treaties. No non-resident DWT would be paid on franked dividends.

Despite the similarities, taxing unfranked inter-entity distributions under Recommendation 11.1 is less complex than the resident dividend withholding tax. Taxing unfranked inter-entity distributions means that unfranked distributions to non-residents will continue to have DWT applied directly to them (rather than the refund arrangements that would be required with the resident dividend withholding tax to achieve the DWT result). Also, under this approach withholding of tax from unfranked distributions to all resident shareholders with associated reporting and advising arrangements is not required. It also reduces the instances in which early refunds of imputation credits will be needed. And tax is also not imposed on unfranked distributions paid directly to tax-exempt entities. Overall, the recommended approach will involve less change from current arrangements.

Relevant also were concerns that applying the resident dividend withholding tax on certain trust distributions to the States may give rise to constitutional issues associated with imposing tax in relation to property of any kind belonging to a State. The taxation of trusts like companies is subject to the same limitations. However, these constitutional limitations depend on the particular nature of a State's interest in the trust property.

The main disadvantage of the recommended option is that it retains the need for the provisions relating to the determination of franked and unfranked dividends. It has less inherent integrity than resident dividend withholding tax because tax applies to the receiver of dividends rather than the payer. As well, an ongoing opportunity remains for dividend streaming (but this also exists under resident dividend withholding tax). Under unified entity taxation, these disadvantages that apply in relation to companies will carry over in the application of the company tax arrangements to trusts. These disadvantages are not judged to be as serious as those that would flow from a deferred company tax with its effects on the reported profits of companies and the taxation of non-resident non-portfolio investors.

Double tax of distributed tax-preferred income

Along with the discussion of options to achieve integrity through the entity chain, the potential for double taxation of distributed tax-preferred income caused by temporary tax preferences is discussed in A Platform For Consultation (Chapter 15, pages 355-360).

This level of taxation arises under the existing law and the issue will remain under any of the three options for improving integrity through the entity chain. However, the deferred company tax option highlights the potential double tax issue because the double tax liability would fall on the paying entity. Under the existing law and the other two options, the second level of liability would fall on the investor. Without deferred company tax there is less need to address this issue.

None of the solutions proposed in A Platform for Consultation is entirely satisfactory from a complexity, compliance cost and revenue perspective. However, in a practical sense, entities usually have sufficient control over their distributions to mitigate the tax at the shareholder level.

The issue is, as noted, a feature of the existing law and has not been raised in the consultation process, except in the context of a deferred company tax, where clearly there is no separation in the incidence and the duplication is readily apparent.

Implications of the general entities regime

The consistent entity tax arrangements (including the taxing of trusts and co-operatives like companies) will mean that distributions to and from these entities will also be subject to the imputation system. Therefore, unfranked distributions received by these entities will be subject to Recommendation 11.1.

Taxing trusts like companies will also mean non-residents investing in trusts will be taxed at the company tax rate rather than the relevant withholding tax rate on distribution. In particular, interest derived by a trust and distributed to a non-resident beneficiary will be taxed at the company tax rate rather than being subject to interest withholding tax. However, this impact of the entity treatment will not affect trusts that are eligible for the flow through treatment of collective investment vehicles (see Recommendation 16.1).

Recommendation 11.2 - Tax refund on unfranked non-portfolio distribution to resident entities of foreign investors

| That entity tax paid on unfranked non-portfolio distributions received by a resident entity that is 100 per cent owned by a non-resident be refunded, but only when the distribution is paid to the non-resident and the non-resident is subject to DWT. |

In A Platform for Consultation (page 352), the Review canvassed the option of relieving foreign investors from the tax on unfranked inter-entity distributions and applying DWT - in order to achieve the same outcome as now when distributions out of untaxed profits pass through the company chain before going to non-residents.

Providing a refund to non-residents of all tax on unfranked inter-entity distributions would involve significant complexity - requiring an additional franking account and related franking rules to track the tax on unfranked distributions though an entity chain. In certain circumstances, income tax on unfranked inter-entity distributions that eventually flow to non-resident non-portfolio investors would significantly increase the Australian tax on direct investment in Australia.

A particular concern is where non-residents invest in incorporated joint ventures in Australia via a resident subsidiary or a consolidated group. Without the recommended treatment, non-residents would be seriously disadvantaged if they invest via an incorporated joint venture rather than via an unincorporated joint venture. The tax system should not impose such an impediment in relation to transactions which are commercially sensible and are often a feature of major projects.

This impact on direct investment will be avoided by a refund of tax on unfranked inter-entity distributions where the entity (or consolidated group) paying the tax is 100 per cent owned by a non-resident and has itself a 10 per cent or greater interest in the entity paying the distribution. The refund will be available to the non-resident parent when a distribution is paid from Australia by the 100 per cent owned entity. Concurrently, DWT will be levied - ensuring that Australia receives the same level of tax as currently (generally at a 15 per cent rate).

Such a refund will be relatively simple because it will be calculated from distributions received and paid by eligible entities. Also, it will involve only a small number of entities.

Recommendation 11.3 -DWT for foreign investors

| DWT exemption on franked distributions

Company tax/DWT switch not adopted

DWT exemption for foreign pension funds exempt at home

|

The prevailing international practice for the treatment of portfolio dividends is for these dividends to be subject to DWT at rates agreed between countries and reflected in double taxation agreements (DTAs). Under the DTAs, investors receive a foreign tax credit in their home country for the DWT imposed.

In A Platform for Consultation (pages 637-642), the Review discussed whether Australian tax on franked portfolio dividends should be limited by continuing not to impose DWT on them or by imposing DWT and refunding some company tax. Termed the Non-Resident Investor Tax Credit (NRITC), the refund of company tax would have been calculated so that it equalled the DWT imposed. Because taxable foreign portfolio investors receive a foreign tax credit for DWT but do not receive a foreign tax credit for company tax paid in Australia, they would benefit from such a 'switch' between company tax and DWT.

The NRITC would be a necessary mechanism in the event that deferred company tax were chosen as the way of achieving integrity through the entity chain - in order to address the impact of deferred company tax on non-resident portfolio investors. As noted under Recommendation 11.1, the NRITC is not necessary with the recommended taxation of unfranked inter-entity distributions. Remaining at issue is whether to introduce the NRITC, in any case, in order to increase the attractiveness of Australia as an investment location for portfolio investors.

If all foreign portfolio investors were subject to DWT, the NRITC would not reduce Australian revenue (as the reduced company tax is matched by increased DWT). Foreign pension funds are, however, currently exempt from the DWT that applies to unfranked dividends. If the partial refund of company tax were to be paid to non-resident investors who are exempt from DWT, the effective tax rate applying to franked dividends would fall from 36 per cent to 25 per cent - or from 30 per cent, if that were the company tax rate, to 18 per cent.

Thus, retaining the DWT exemption for foreign pension funds and introducing the NRITC would cost about $190 million per annum if foreign pension funds provide 50 per cent of portfolio investment (as suggested by the available information). With roughly equivalent proportions of taxable and tax exempt foreign investors, the cost to Australian revenue of providing the NRITC to the exempt foreign pension funds is equal to the increased crediting of Australian DWT for taxable investors by other countries. Moreover, a refund mechanism would be needed with the NRITC for foreign pension funds because of this tax exempt status. This reform would be complex, involving companies and intermediaries (such as nominee companies) administering the refund or providing information to the Australian Taxation Office to allow it to make the refund.

If, instead, the foreign pension fund DWT exemption were to be removed, Australia's tax on some unfranked dividends would increase from zero to 15 per cent. The small proportion of portfolio dividends that are unfranked means that this impost is likely to be small (less than $20 million). Moreover, it would be outweighed by the effect on the foreign pension funds of any reduction in the company tax rate (roughly $10 million per percentage point).

Nevertheless, removing the DWT exemption from foreign pension funds may be perceived as increasing the tax burden on these investors and decreasing the attractiveness of Australia as an investment location.

Because of the significant revenue cost, the complexity of the refund and some uncertainty about the acceptability of the NRITC to other countries, the company tax/DWT switch will not be adopted.

Recommendation 11.4 - Preventing double tax on inter-entity distributions

| That the existing section 46 inter-corporate dividend rebate be replaced with a gross-up and credit approach for preventing double tax on distributions passing between resident entities (outside of consolidated groups). |

Three options for preventing double tax on distributions as they pass through an entity chain were canvassed in A Platform for Consultation (Chapter 17, pages 390-398):

- •

- gross-up and credit;

- •

- exempt the franked portion of distributions received; and

- •

- rebate franked inter-entity distributions (similar to the existing section 46 inter-corporate dividend rebate, but only applying to the franked portion of a distribution).

All the options prevent double tax through the entity chain. The exemption option is not preferred because deductions would be denied for expenses incurred in deriving the distribution (unless special measures were developed to prevent such an outcome).

The gross-up and credit approach is the same mechanism used to determine tax payable on dividends received by individuals and superannuation funds. The taxable income of the entity receiving a franked dividend is determined under this approach by adding the imputation credit to the cash dividend received. Recommendation 11.4 will therefore provide a simple and consistent treatment of distributions through the entity chain and out to individual investors.

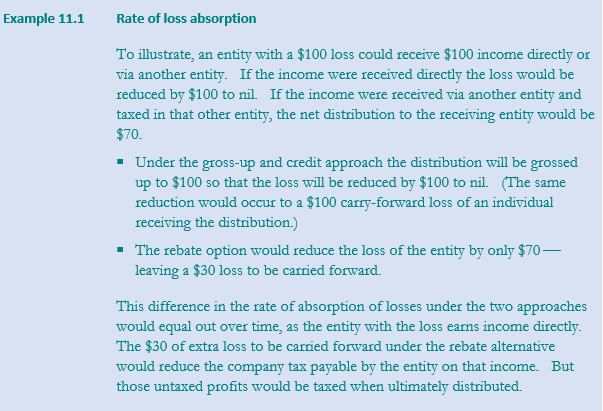

Losses in the entity chain are the source of the main difference between the gross-up and credit approach and the alternative inter-entity rebate. Because of the grossing up of the cash distribution by the attached imputation credit, the gross-up and credit approach absorbs losses faster than the inter-entity distribution rebate. The rate of absorption under the gross-up and credit approach will correspond to the reduction in the loss that would occur if the income reducing the loss were earned directly by the entity with the loss (rather than being received by that entity as a distribution via an interposed entity). It is also the same reduction that would occur if an individual with a carry-forward loss received the income directly or via a distribution.

Example 11.1 illustrates how losses are absorbed under the two approaches.

During consultation the main concern raised related to the rate of absorption of losses through the entity chain. An alternative proposal was to allow a dividend-received deduction similar to the deduction available under the US tax system. Such a deduction would, however, effectively reverse the tax on unfranked inter-entity distributions recommended earlier - with the accompanying integrity problems of the present arrangements.

The next recommendation on carry-forward losses is intended to alleviate most of the concerns raised during consultation about the interaction of losses with the gross-up and credit approach.

Recommendation 11.5 - Deduction for carry-forward losses

| That entities (including consolidated groups) be able to choose the proportion of their carry-forward losses to be deducted in a year. |

During consultation two main concerns were raised about the effect of distributions on losses.

- •

- First, as noted in respect of Recommendation 11.4, concern was raised about the rate of absorption of losses under the gross-up and credit approach for preventing double tax through the entity chain.

- •

- Second, concerns were raised that the proposed consolidation regime would force groups to apply distributions received by them to losses earlier than under the existing law. Currently, groups usually ensure that distributions from outside the group are paid to the holding company with any losses held by subsidiaries. Under the current loss transfer provisions, the holding company and subsidiary can agree on the amount of loss to be transferred. This allows the holding company the option of not absorbing group losses against distributions received by the holding company from outside the group. The pooling of group losses under consolidation would remove this option in the absence of a specific measure.

Both these concerns will be overcome by allowing entities (including consolidated groups) to choose the proportion of carry-forward losses to be deducted in a year. Under the current law, a company cannot choose the amount of carry-forward loss it wishes to deduct. A company is forced to claim the amount of loss necessary to absorb the excess of assessable income over allowable deductions. As noted, in contrast, under the existing loss transfer provisions, groups can choose the proportion of loss to transfer within the group.

The recommended measure will allow consolidated groups and single entities - as well as unconsolidated groups - to avoid having a carry-forward loss absorbed by grossed-up franked distributions received from other entities or groups. This will provide consistency of treatment across these taxpayers. It also provides a mechanism for single entities or groups to fully frank distributions of profit even when they have large carry-forward losses. By not fully claiming the losses, the group or entity could pay sufficient tax to frank the distributions.

Carry-forward losses will still have to be reduced by the amount of net exempt income derived by an entity, consistent with the existing law.

This measure will not apply to individuals or complying superannuation funds. Unlike entities, individuals and complying superannuation funds will not be affected by the absorption of carry-forward losses by franked distributions received by them. The proposal to refund excess imputation credits effectively gives these taxpayers the full benefit of the losses immediately.

Simplification of the franking account

Recommendation 11.6 - Operation of the franking account

|

That the franking account be simplified by:

|

Measures on how the franking account could be simplified were canvassed in A Platform for Consultation (pages 380-381, 383 and 389). The Review recommends adopting three of those measures.

Tax-paid basis of operation

Under the current law, the franking account is operated on a taxed-income basis so that the balance in the franking account reflects the amount of franked distributions able to be paid. The difficulty with this approach is that it requires grossing up of most entries to the franking account to reflect taxed income. The taxed-income basis also led to the creation of the complex multiple franking accounts (the Class A, B and C franking accounts) in response to company tax rate changes.

The recommended approach is to operate the account on a tax-paid basis so that grossing up will not be required for most entries to the account. This approach will avoid further proliferation of franking accounts as no adjustment will be made on change of the company tax rate. However, on making a distribution, an entity will need to gross up the balance in the franking account to determine the amount of franked distribution.

Because companies are now used to operating on a taxed-income basis, changing to a tax-paid basis may inconvenience some companies. Nevertheless, other entities, such as most trusts, will be using a franking account under the new entity system for the first time. Consultation on this issue has supported the change to a tax-paid basis.

Alignment of income and franking year

The second proposal, to align the income year and franking year, will correct an anomaly in the existing law that some late balancing companies have a franking year which is different from the income year. The current complexities will be removed for these companies without affecting other entities.

Adoption of a standard rate of franking

The possibility of further simplifying the franking account by adopting a standard annual franking allocation rule as under the New Zealand imputation system was raised in A Platform for Consultation (page 389). This would be intended to limit the opportunities for dividend streaming, but in a simpler manner. Under the recommendation, which is a variant of the New Zealand approach, the existing complex franking rules will be replaced with a requirement that entities adopt a standard rate of franking for all distributions made during a half-year.

Features of this proposal include:

- •

- entities, apart from widely held entities with a single class of membership, identifying, prior to the first distribution in a half-year, a standard rate of the franked portion of distributions to be made during the half-year;

- •

- the standard rate applying to all distributions, irrespective of class of membership, during that half-year; and

- •

- entities being free to set any standard rate, but:

- -

- if an entity overfranks it will have to pay franking deficit tax;

- -

- the franking deficit tax will not be creditable against future income tax liability, otherwise it would reinstate tax preferences and would be inappropriate in a system with refundable imputation credits;

- -

- entities will only be able to vary their standard rate in a half-year in exceptional circumstances, and measures will be needed to prevent excessive variation of rates between half-years, in order to limit opportunities for dividend streaming.

The measures will simplify the franking rules while reducing the opportunities for dividend streaming. It will especially benefit widely held entities which have a single class of membership interest because they will not be subject to franking restrictions. It will also provide all entities with the ability to introduce more certainty in franking policy over a number of years. The main concern is that it effectively locks entities into a rate of franking irrespective of what happens during the half-year. This is partly overcome by the fact that many entities, especially the large corporates, will only distribute once in a half-year. Furthermore, widely held entities that have a single class of membership will be free to vary their franking rate between distributions within a half-year if, for each of those distributions, the entity makes equal distributions on all membership interests.

Refunding excess imputation credits

Recommendation 11.7 - Refunds of excess imputation credits

| Refunds of excess credits available to certain residents

Early refunds of excess credits in certain circumstances

Refunds related to donations to registered charities

|

Access to refunds

In A New Tax System, the Government proposed refunds of excess imputation credits for resident individuals and complying superannuation funds. The Review supports this measure, which will ensure that such taxpayers are taxed at their appropriate marginal rates of tax on assessment.

Access to early refunds

It was recognised in A New Tax System (Chapter 3, page 118) that consistent entity tax arrangements (including the taxing of trusts and co-operatives like companies) which incorporated full franking of distributions may impose adverse cash flow consequences on low marginal rate taxpayers despite the availability of refunds of excess imputation credits on assessment.

In contrast with the universal 'full franking' effect of the deferred company tax canvassed in A New Tax System, the Review has recommended taxing unfranked inter-entity distributions (see Recommendation 11.1). This will mean that entities will be able to continue to distribute tax-preferred income earned in the entity as unfranked distributions. To some extent this lessens the cash flow impact on low marginal rate investors who receive unfranked distributions.

The Review also recommends (see Section 16) flow-through treatment of collective investment vehicles (CIVs), rather than including CIVs in the entity tax arrangements (see Recommendation 16.2). This will remove the potential cash flow impact on low marginal rate trust beneficiaries who derive their income largely from CIVs.

Investors in widely held entities are unlikely to suffer a cash flow disadvantage from the proposed entity taxation arrangements. Shareholders in companies will benefit from the refundability of excess imputation credits relative to the current law, and unitholders in CIVs will enjoy flow-through treatment.

Nevertheless, beneficiaries of some trusts will face adverse cash flow consequences from the taxation of trusts like companies. This is a particular issue for small businesses, and underlines the case for provision of early refunds to individual investors in closely held entities. In contrast with the high compliance costs for widely held businesses of providing an early refund mechanism, closely held entities have a greater ability to control the timing and amount of distributions, thereby facilitating an early refund mechanism where entity tax is paid.

Members of co-operatives, including widely held co-operatives, may also suffer cash flow disadvantages. Often the co-operative members will sell their produce to the co-operative for a price below the market rate, with the balance arriving via a co-operative distribution. Therefore, the distributions may be more significant than a distribution from other widely held entities.

The flow-through taxation of CIVs, the receipt of unfranked distributions, and the virtual pooled superannuation trust treatment for life companies address the cash flow issue for complying superannuation funds. The Review therefore does not recommend extending the early refund mechanism to complying superannuation funds. Refunds to such funds will of course still be available on assessment.

Providing early refunds

Two possible approaches of providing early refunds of excess imputation credits are canvassed in A Platform for Consultation (Chapter 15, pages 363-366):

- •

- providing a refund at the entity level so that distributions to eligible beneficiaries are gross of company tax; or

- •

- allowing an option for refundable credits to be claimed through instalments during the course of the income year.

The recommended option is to require closely held entities (defined in Recommendation 6.22) and all co-operatives to provide refunds at the entity level. This is the best option for the taxpayer entitled to a refund, because there is no double handling or time delay between the receipt of the distribution and the refund. It also obviates the need for non-lodging investors to lodge a return just to obtain the refund.

Receipt of refunds

The mechanism for providing the refund at the entity level will include the following requirements:

- •

- an eligible member notifying the distributing entity of their election to obtain early refunds of excess imputation credits, as well as a selected rate of 'withholding', chosen from a range of rates (for example, 0, 5, 10, 15, 20 or 25 per cent);

- •

- the distributing entity effecting early refunds to those members by paying distributions gross of entity tax, but not of the selected withholding rate, to those members;

- •

- the distributing entity reducing its net PAYG payments to take account of the early refunds of excess imputation credits made to its members;

- •

- advice for members still to show the franked portion of the distribution to facilitate assessment where necessary; and

- •

- members receiving early refunds will not have to lodge returns simply because of the receipt of the refund, unless, as now, their income level requires lodgement.

Those taxpayers who have not accessed early refunds will still be able to receive the refund on assessment.

Tax-exempt members

During consultation a number of submissions sought refunds of excess imputation credits for all or some tax exempts. In A Platform for Consultation (Chapter 15, pages 362-363), it was explained that in A New Tax System the Government proposed a refund of imputation credits for tax paid at the trust level on 'donations' to registered charities by way of trust distributions. The Review recommends that approach, which will maintain the current net tax position of such donations.

A common start date for entity taxation

Recommendation 11.8 - Commencement of entity taxation regime

| That subject to Recommendation 11.9, the entity tax arrangements apply to all entities from the same date. |

The entity tax system is intended to apply from a particular income year. Most entities have an income year that corresponds with the usual financial year commencing on 1 July.

For early balancing entities, applying the regime from the beginning of their 2000-01 income year could potentially mean that they would have little or no notice of all the details of the legislation covering the entity tax system prior to that time.

A common start date avoids these problems, but involves additional complexity in the legislation and associated higher compliance costs for entities with early and late balancing dates. Such entities may have to prepare two separate tax calculations for the affected income year so as to cover the different arrangements applying to the periods before and after 1 July.

Notwithstanding this disadvantage, consultations have indicated support for a common start date.

Reducing the company tax rate

Recommendation 11.9 - Phased reduction in company tax rate

|

That the company tax rate be reduced:

|

A 30 per cent tax rate

The removal of accelerated depreciation, and other reforms to the business income tax system, provide scope within the revenue neutrality constraint to reduce the company tax rate to 30 per cent from the 2001-02 income year. That constraint will provide for a 34 per cent rate for the 2000-01 income year, but with no variation in instalments permitted before 1 July 2000. Revenue neutrality aside, the 30 per cent rate has structural advantages as it will align the company tax rate with the 30 per cent marginal tax rate applicable to most individual taxpayers.

Moreover, a 30 per cent tax rate will make the headline rate of corporate tax internationally competitive, both in terms of the Asia Pacific region and compared with the corporate tax rate operating in capital exporting countries.

By providing a competitive corporate tax rate, non-portfolio foreign investors in Australian companies can benefit because they will be better placed to utilise foreign tax credits available in their home jurisdictions - reducing the possibility of foreign tax credits being lost because the Australian tax rate is higher than their home country rates. For portfolio investors who receive no credit in their home country for underlying company tax, reducing the tax rate directly increases their after-tax return from investing in Australian stocks. More generally, a low company tax rate is a strong signal to the foreign investor, especially if accompanied by a clear and user friendly tax system.

By increasing Australia's attractiveness as an investment location, a lower company tax rate strengthens Australia's prospects for investment, economic growth and jobs. Crucial to this are the accompanying reforms to the business investment base because they will attract investment to where it will be most productive, not where a faulty tax system channels it. The strength of Australia's commercial base and the long-run growth potential of Australia are bolstered as a result.

Reducing the corporate tax rate will also enable Australian companies to maintain dividend flows to shareholders while increasing the levels of retained income and investment.