Review of Business Taxation

A Tax System RedesignedMore certain, equitable and durable

Report July 1999

SECTION 22 - ALLOCATING INCOME BETWEEN COUNTRIES

Strengthening thin capitalisation provisions

Recommendation 22.1 - Wider application of the thin capitalisation regime

| That the thin capitalisation regime be strengthened by applying it to the total debt of the Australian operations of a foreign multinational investor, including permanent establishments (that is, branches) operating in Australia. |

The fundamental differences in the tax treatment of debt and equity can heavily influence the financing of investment in Australia. As discussed on page 703 of A Platform for Consultation, foreign multinational groups often have the flexibility to allocate a disproportionate share of debt to their Australian operations with detrimental revenue consequences.

Many developed countries have thin capitalisation rules that seek to limit the tax recognition of debt financing of entities controlled by non-resident investors. These rules impose pragmatic restrictions hence a balance has to be drawn between revenue protection and allowing for wide variations in commercial arrangements.

Australia's current thin capitalisation provisions are not fully effective at preventing an excessive allocation of debt to the Australian operations of multinationals because they refer only to foreign related party debt and foreign debt covered by a formal guarantee rather than total debt. Hence, they do not restrict the proportion of third party debt that can be allocated to the Australian operations.

Whilst the thin capitalisation rules have the potential to disallow deductions for interest in highly geared cases, the more likely response by foreign multinationals will be to restructure their arrangements to decrease the gearing of the Australian operations.

Strengthening the provisions to include total debt has received the support of several major business groups during consultations.

Entities that decide to carry on a business in Australia can do so via a subsidiary or a branch. Consistent with the investment neutrality principle set out in A Strong Foundation (page 69), the tax system should avoid treating such alternatives differently. Requiring all permanent establishments (PEs) to be capitalised (including with equity) for tax purposes will reduce these differences. The tax treatment of branches is discussed further in Recommendation 22.11.

Recommendation 22.2 - Thin capitalisation regime - applicable tests

| Safe harbour gearing ratio

Arm's-length test in default

|

A Platform for Consultation (page 704) contains two options for the operation of the thin capitalisation regime.

Option 1 would permit the Australian operations to gear up to the gearing level of the worldwide group of which they are a part. Where that level is exceeded, an arm's-length test would determine whether the gearing level is higher than that which could be expected in a comparable but independent operation.

This option would be flexible because it would basically allow the financial markets to limit gearing rather than setting statutory limits. However, the use of the worldwide gearing of the group has received little support during the consultation process, with several submissions stating that the costs of complying with this option would outweigh the perceived benefits it would bring.

Option 2 would set a fixed safe harbour gearing ratio that, if exceeded, requires an enterprise to compare itself with the worldwide gearing level of the group to which it belongs or to satisfy an arm's-length test. Several submissions (in particular, those from companies with mining and infrastructure assets) suggest that where the safe harbour ratio is exceeded, an arm's-length test determine whether the gearing level could have been borne by an independent party operating under the same conditions and terms.

Recommendation 22.3 - Safe harbour gearing level - general treatment

| That except for financial institutions (Recommendation 22.4), the safe harbour gearing level be set at a ratio of 3:1 debt to equity (total shareholders' funds). |

Careful judgment is required in setting the safe harbour gearing level. A low safe harbour ratio would place greater restrictions on gearing levels while a higher level would give taxpayers greater freedom to choose their own funding structure, but with potential detrimental effects to Australian revenue. Providing comparable treatment to other countries is also important.

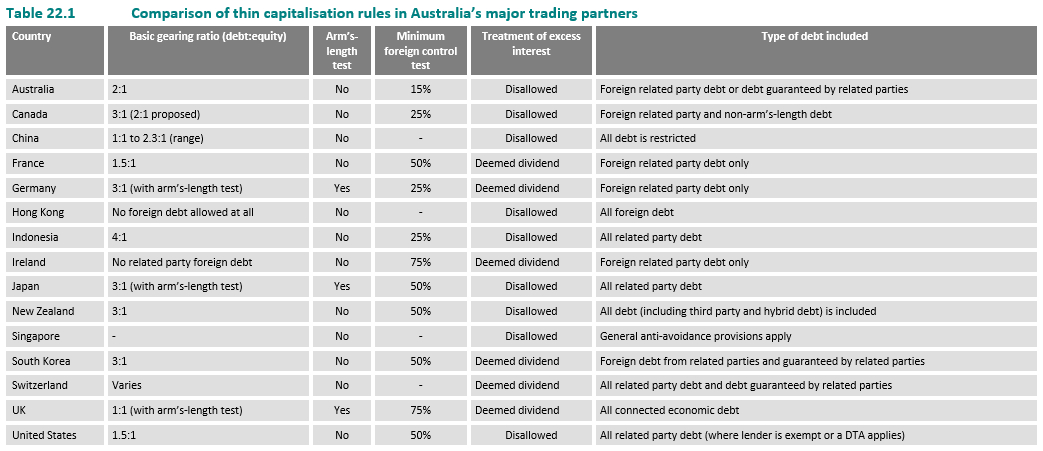

The existing thin capitalisation regime uses a gearing ratio of 2:1, but this ratio only includes foreign related party and parent-guaranteed debt. Table 22.1 provides a comparison of the thin capitalisation rules of Australia's major trading partners. Recognising that total debt is being included in the rules, and having regard to the treatment provided in other countries, the Review recommends a ratio of 3:1 be adopted.

Recommendation 22.4 - Safe harbour gearing for financial institutions

| Financial institutions subject to capital adequacy rules

Financial institutions not subject to capital adequacy rules

|

Due to the particular nature of the business they conduct, banks and finance entities maintain much higher levels of debt than non-finance entities. It is necessary to recognise this fact within the thin capitalisation regime so as not to impose requirements that will unduly limit the ability of these entities to operate commercially.

Licensed Australian banks and certain other financial institutions are subject to prudential regulation by the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority, including the requirements to maintain minimum levels of capital. However, these entities often maintain capital at levels well above the minimum required.

The capital levels reported by these financial institutions for regulatory purposes would form the basis of the thin capitalisation rule for these entities. Such a rule would also be applied to foreign bank branches operating in Australia based on their capital levels reported in their home jurisdiction.

For other financial institutions such as merchant banks and finance companies, thin capitalisation rules based on the capital levels applying to banks will not always be appropriate. These entities conduct a broad range of business in the finance sector, ranging from the provision of advice on mergers and acquisitions to lending to companies. Some of this business, namely the provision of loans, is principally financed by debt funding, whilst the provision of financial services and advice does not need to be financed by debt funding to the same degree. Consequently, each of these entities will have different requirements for debt funding.

Variations in lending activity (as a proportion of total business) across these financial institutions will be addressed by an 'on-lending' rule that removes from the thin capitalisation calculations any debt that is 'on-lent' to third parties. The remaining debt, which is used to finance the non-lending business of the entity, would be subject to the general safe harbour gearing level.

An 'on-lending' rule could allow financial institutions that are primarily involved in lending to have less capital for tax purposes than would be required for prudentially supervised institutions. This is because capital that actually supports the lending business could effectively be counted, for tax purposes, as supporting the non-lending business. Consequently, the total gearing for taxation purposes of financial institutions that are subject to the on-lending rule will be limited to 20:1. This gearing level is broadly consistent with the minimum capital adequacy requirements that apply to licensed banks.

Recommendation 22.5 - Thin capitalisation rules for Australian multinational investors

| Application to non-portfolio offshore investments

Safe harbour rules

Default rules based on worldwide gearing

|

In a similar manner to foreign multinationals, Australian multinationals that have non-portfolio investments in controlled foreign entities or offshore branches can be in a position to allocate excessive debt to their Australian operations. This can result in an undue proportion of the interest expense being borne by the Australian revenue. The multinational may allocate the underlying debt to its Australian operations to gain an unwarranted tax advantage where it currently gets a full deduction, regardless of how highly the Australian operations are geared relative to the foreign investments. Expansion of the conduit regime to encompass more foreign income adds to the need for some control on interest deductions to prevent interest incurred in deriving untaxed conduit income being used to reduce domestic income.

A safe harbour ratio of 3:1 - consistent with that for the Australian operations of multinational investors - will provide simplicity and, in practice, would exclude most Australian multinational companies from the provisions.

Australian financial institutions with controlled foreign subsidiaries or offshore PEs will be subject to the thin capitalisation rules outlined in Recommendation 21.4. For financial institutions subject to capital adequacy rules, the safe harbour gearing levels would be based on the capital levels reported for regulatory purposes.

The ability to gear the Australian operations up to 120 per cent of the worldwide gearing ratio accommodates businesses with a high level of gearing in Australia that need equity to expand offshore. A worldwide gearing ratio would have lower compliance costs for Australian-controlled groups than for foreign multinationals because the Australian groups report their group profits using Australian accounting standards.

There has been broad opposition in consultations to limits on the gearing of Australian companies with offshore investments. Many claim that Australia's imputation system provides an incentive for company tax to be paid in Australia rather than overseas when this is feasible (as noted in A Platform for Consultation, page 702). Some submissions have also stated that the rules should only apply if it can be shown that Australian gearing is high over the long term and that interest deductions should then be deferred rather than disallowed. The Review considered these views but believes that the recommendation is reasonable and equitable, particularly taking into account Recommendation 22.6.

Recommendation 22.6 - Interest incurred in deriving foreign source income

| That upon adoption of Recommendation 22.5, the current law be amended so that interest expenses incurred in earning foreign source income are no longer quarantined. |

The current law requires taxpayers to determine (by tracing and matching) expenses incurred in earning foreign source income. Interest expenses are not deductible to the extent that they are incurred in deriving foreign source income that is not taxed in Australia. If interest expenses exceed assessable foreign income in any given year, the excess may not be deducted against other assessable income, but must be carried forward to later years for possible deduction against future assessable foreign income.

In practice, however, because of the fungibility of debt, financing of investments can be structured within company groups so as to conform with this law. The structuring can result in foreign investments being fully equity funded while interest deductions are claimed against domestic investments.

If this recommendation (together with Recommendations 22.5 and 22.8) were adopted, the thin capitalisation requirements will be the only restriction on the deductibility of interest where Australian taxpayers borrow for investment in controlled foreign entities. Compliance costs will be reduced by removing interest expenses from the operation of the current quarantining provisions.

With this change, no restrictions will apply on the gearing of the foreign source income of Australian taxpayers that have no foreign non-portfolio investments.

Recommendation 22.7 - Control test for thin capitalisation

| That the thin capitalisation regime adopt the control test used in the Controlled Foreign Company (CFC) regime - raising the threshold for foreign control from 15 per cent to 50 per cent in most cases. |

The control test in the current thin capitalisation regime requires only 15 per cent control in determining whether an Australian investment is foreign controlled. The CFC control test requires 50 per cent control (or 40 per cent where there is no other person with the ability to control). Introducing a higher threshold for control that is consistent with the CFC control test will reduce compliance costs. Most foreign-owned investments are subject to 50 per cent or higher control, so moving to a 50 per cent control test will have minimal effect on the number of entities subject to thin capitalisation rules.

Recommendation 22.8 - Debt creation rules

| That the debt creation rules be repealed. |

The debt creation provisions, which supplement the current thin capitalisation provisions, limit interest deductions where a foreign-controlled company sells an asset to a related foreign-controlled company. The provisions disallow interest deductions where the transfer of an asset is financed using interest bearing debt that is introduced from outside the corporate group.

The need for such rules is removed with the Review's recommendation of a thin capitalisation regime that applies to the total debt of the Australian operations of a foreign-controlled group. Removing the rules will reduce complexity and uncertainty without compromising the integrity of the interest deductibility regime.

Recommendation 22.9 - Implementation of thin capitalisation reforms

| That no special transitional provisions for existing investments be adopted. |

The proposed changes to the thin capitalisation rules would be introduced along with the broad changes to entity taxation. In the first year of operation, the thin capitalisation test will be applied at the end of a taxpayer's accounting period. This will give business adequate time to restructure or otherwise reduce their debt levels.

An appropriate treatment of branches

Recommendation 22.10 - No tax to be levied on remittances by branches of foreign companies

| That a tax on remittances of untaxed profits made by domestic branches to their foreign parent companies not be introduced. |

As discussed in A Platform for Consultation (pages 643-645), greater consistency between branches and subsidiaries could be achieved by levying a tax equivalent to dividend withholding tax (DWT) on branch remittances. This would require the remittances made by a branch to be determined by reference to the accounting profits of the branch and the assets retained in the branch. There would be significant complexity involved in measuring the remittances because of the need to ensure that accounting records sufficiently reflect the total profits of the branch.

If deferred company tax had been recommended, this increased tax on dividends paid by subsidiaries would have resulted in a greater bias in favour of branches and would have created a stronger case for an equivalent tax on branches. However, under the recommendation for achieving integrity through the entity chain by taxing intercorporate dividends (Recommendation 11.1), the advantage for branch remittances would continue to be the absence of an equivalent to DWT. If lower non-portfolio DWT rates were to be negotiated in Double Taxation Agreements (DTAs), as separately recommended by the Review (see Recommendation 22.21), this advantage will be further reduced.

While the conceptual argument for a tax on branch remittances is clear, the complexity required to achieve it and the objective of lower DWT rates militate against introducing such a tax.

Recommendation 22.11 - General treatment of branches

| Progressive introduction of separate entity treatment

Application of thin capitalisation rules

Preparation of financial accounts

|

With the exception of branches of foreign banks that are taxed under specific provisions, the current taxation treatment of branches is unclear (A Platform for Consultation, page 707).

Ideally branches would be treated as separate entities so that the taxable income of the branch correctly reflects the profits attributable to the branch. This would result in a more equal treatment of branches and entities such as companies. The treatment of branches within member countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) is moving in this direction. However, some caution needs to be exercised in how far such an approach is implemented where there is not a consensus within the OECD.

Dealings involving trading stock

For this reason, the Review's recommendations are limited at this stage to those that are consistent with the treatment in other countries and are consistent with Australia's DTAs.

Where trading stock is supplied to or acquired from other parts of the entity, taxable income of the branch will be determined by applying arm's-length prices to those dealings calculated as if the dealings were between unrelated entities. This change will apply to Australian branches of non-residents and to the foreign branches of residents.

The transfer of other assets between the branch and the rest of the entity will not be addressed at this time as there is not an international consensus on this issue. For the same reason, withholding taxes will not be extended to intra-entity interest and royalty payments (beyond the present foreign bank branch provisions).

The progress of deliberations at the OECD on the broader application of this approach to branches should be monitored and further elements of the approach could be considered if the OECD reaches consensus on other types of dealings.

Thin capitalisation rules

The thin capitalisation rules will apply to branches of non-residents to ensure that these branches are required to have some minimum level of equity for the purpose of determining interest deductions.

Most foreign bank branches operating in Australia are currently taxed under the foreign bank branch provisions. These provisions contain a notional equity requirement that has a similar objective to the thin capitalisation rules. However, foreign bank branches can elect not to be treated under the foreign bank branch provisions and in these circumstances the level and method of calculation of equity capital required for taxation purposes is not clear.

Applying the thin capitalisation rules to all foreign bank branches will ensure that all such branches are treated consistently and clarify the level of capital required for branches that elect not to be treated under the foreign bank branch provisions.

As discussed in Recommendation 22.4, the thin capitalisation rule for financial institutions that are subject to capital adequacy requirements (including in their home jurisdiction) will be based on the capital levels reported for regulatory purposes. For foreign bank branches these rules will replace the current notional equity requirement contained in the foreign bank branch provisions. The current requirement can be harsher than a thin capitalisation rule because it denies a proportion of a foreign bank branch's interest deduction irrespective of the level of interest-free capital in Australia.

Financial accounts

To assist in the calculation of their profits, branches will be required to prepare and submit financial accounts (balance sheet and profit and loss account) that include dealings with other parts of the entity.

Modifying the transfer pricing rules

Recommendation 22.12 - Transfer pricing on a self-assessment basis

| That Australia's international transfer pricing rules be modified to apply on a self-assessment basis. |

Consultation and submissions supported this approach (discussed in A Platform for Consultation, pages 705-706) and indicated that many businesses currently self-assess in practice. This is despite the current provisions formally requiring the Commissioner to exercise a statutory discretion to apply an arm's-length consideration to dealings which have been undertaken on a non-arm's-length basis and that reduce Australian revenue (that is, where profits have been shifted offshore). This recommendation is consistent with the general self-assessment structures of the income tax law.

Some submissions also raised the question whether self-assessment for transfer pricing should extend to non-arm's-length dealings that increase Australian revenue (that is, where profits have been shifted to Australia). This is not internationally accepted practice and is not recommended. Countries typically only provide for a reduction in their tax revenue as a result of transfer pricing adjustments through DTAs.

Recommendation 22.13 - Transfer pricing - record keeping rules

| Contemporaneous documentation of arm's-length application

Penalty provisions to reflect reasonable efforts

|

The existing record keeping provisions in the income tax law (section 262A of the 1936 Act) do not include any specific reference to documentation relating to international non-arm's-length dealings. A requirement for contemporaneous documentation - to obtain readily accessible data and evidence the application of that data to the arm's-length principle - would assist multinational enterprises to apply the arm's-length principle under self-assessment. It would also facilitate subsequent validation by the Commissioner of Taxation. The contemporaneous element could apply when the non-arm's-length dealing is being entered into where transactional methodologies are used. Where profit-based methodologies are used, the contemporaneous element could operate at the time of preparation of the income tax return.

A tax shortfall penalty under the general penalty provisions would apply to support the requirement to keep contemporaneous documentation for non-arm's-length dealings. Where enterprises make objective efforts to apply the arm's-length principle but do not succeed, the general penalty provisions will reflect their efforts and the difficulties in applying the arm's-length principle. Reduced penalties will apply where contemporaneous documentation requirements are satisfied. Penalties will be reduced to nil in circumstances where the taxpayer has made legitimate attempts to determine an arm's-length price and contemporaneous documentation has been maintained but the Commissioner has relied on the use of confidential data which is not readily accessible to the taxpayer.

The higher penalties that apply where the tax shortfall is due to recklessness or intentional disregard would also apply to transfer pricing adjustments.

Recommendation 22.14 - Transfer pricing - consequential adjustments

|

That appropriate consequential adjustments be available to avoid double taxation arising from:

|

Currently consequential adjustments can and are made where an amount has been included in a taxpayer's assessable income or where a deduction has been adjusted to take account of dealings carried out on an arm's-length basis. However, there is no legislative support to adjust, for example, royalty withholding tax where a royalty deduction has been reduced.

Australia's tax treaties impose an obligation on both tax treaty partners to relieve double taxation where a transfer pricing adjustment has been made by the other country in accordance with the treaty. There is currently uncertainty in the way these provisions achieve their aim and in some cases inadequate relief may result (for example, where one of the parties is in a loss situation, or in the royalty case referred to above). Legislation is needed to ensure that the relief from double taxation matches what would have been the outcome had the dealings been undertaken on an arm's-length basis in the first place.

Recommendation 22.15 - Franking account adjustments to be modified

| That the limited secondary adjustment provisions, which prevent a franking credit arising from tax paid as a result of a transfer pricing adjustment, be modified to remove the potential for disadvantage to Australian multinationals. |

Current legislation does not allow a franking credit to arise when tax is paid as a result of a transfer pricing adjustment. Where profits are shifted from a resident subsidiary to a foreign parent company, the resident subsidiary does not require a franking credit to relieve the distribution of those profits from dividend withholding tax because the profits have already left the country.

Business representatives have argued that these provisions disadvantage Australian multinationals. In circumstances where non-arm's-length dealings have resulted in profits being shifted from Australia to a non-resident subsidiary, the profits remain within the group for return to the Australian parent and distribution at some future time. When these returned profits are distributed the current legislation would result in the distributions being unfranked, even though tax has in fact been paid.

The perceived disadvantage to Australian multinationals could be alleviated to a large extent by providing a carve-out from the current legislation for profits shifted offshore to wholly owned subsidiaries of Australian multinationals. This approach is relatively simple, but it may not deal adequately with potential disadvantage to offshore joint venture arrangements.

An alternative approach has been suggested which would apply where profits have been shifted from Australia in circumstances equivalent to a distribution to a non-resident parent company. Under this approach an imputation credit would arise from payment of the tax and an imputation debit would arise from the payment of a 'deemed dividend'. This achieves the same result as the current legislation but does not disadvantage Australian multinationals as a dividend is not deemed where profits are shifted to a subsidiary.

To ensure parity with the 'deemed dividend' approach, other mechanisms are needed to deal with circumstances where profits are shifted from an Australian resident company to an offshore subsidiary or sister company. In these circumstances the profits shifted would not be in the nature of a dividend. Mechanisms used by other countries include repatriation of the transferred profits to the parent, a deemed injection of equity in a subsidiary or a deemed loan to a sister company. Complex ownership rules are also used to prevent avoidance through re-routing of profits.

Recommendation 22.16 - Transfer pricing - further improvements to administration

| That further legislative changes be developed to improve administrative arrangements for transfer pricing. |

A number of other issues, some outlined in A Platform for Consultation (pages 705-707), could be further developed with the objective of providing a clearer legislative framework for improving administrative arrangements for transfer pricing. These issues include:

- •

- the usefulness of provisions to support and clarify the operation of advance pricing arrangements;

- •

- how to improve domestic and international dispute resolution mechanisms for transfer pricing issues;

- •

- rules to link transfer prices for customs and income tax purposes;

- •

- a legislative requirement to use the most appropriate methodology and whether internationally acceptable methodologies (both transaction and profit) should be identified with some criteria for selection of the most appropriate methodology; and

- •

- the treatment of interest-free loans provided by an Australian resident to fund offshore operations and consistency with the application of the thin capitalisation rules.

Foreign expatriates and residents departing Australia

Recommendation 22.17 - Non-residents' salary and wage income in Australia

| That non-residents' salary and wage income be subject to a final withholding tax at the company rate (see Recommendation 21.6 for further details on the withholding arrangements). |

The globalisation of capital markets is being accompanied by the globalisation of related markets, such as markets for innovative technologies and skilled labour.

Australia's taxation rules (including its DTAs) should not result in unrelieved double taxation (or non-taxation) of the income of people who move between Australia and other countries in the course of their employment - and not impose excessive costs on local businesses employing foreign expatriates. Three specific business tax recommendations are made below in relation to foreign expatriates and residents departing Australia. However, a wider review of personal taxation issues may identify other changes which need to be made to ensure that Australia's tax arrangements are appropriately treating internationally mobile executives and skilled employees generally.

Non-residents' personal services income in the form of wages and salaries is currently generally taxed using the progressive tax rate scale - but excluding the zero bracket and lower rates available to residents. That means that from 1 July 2000 the tax rates on this income will vary from 29 per cent to 47 per cent. The people - including foreign expatriates - earning this income are likely to be subject to further taxation in their home country, perhaps with a credit for Australian tax.

Australia's top rate of 47 per cent may be too high for Australia's tax to be fully creditable. Furthermore, taxation on a progressive scale is generally only appropriate for the country in which a person is resident. The practical force of this is illustrated where a non-resident has non-Australian income - it is not practical for Australia to take that income into account when levying tax, and only their country of residence can take account of worldwide income in determining an appropriate tax rate.

Thus, the recommendation to fix the rate on non-resident income at the company rate should be of significant benefit to those non-residents temporarily providing expertise to business in Australia. Making the company rate a final tax for wages and salaries should also assist greatly with simplification of compliance and administration.

Recommendation 22.18 - Foreign expatriates - pre-residence assets and liabilities

|

That individuals who enter Australia on a temporary entry permit where the visa is for four or fewer years' duration - and become residents for tax purposes for the first time be exempt from:

|

The current taxation treatment of foreign expatriates who become temporarily resident in Australia for tax purposes could discourage some multinational enterprises, particularly skill intensive businesses, from locating in Australia.

For example, until recently a number of foreign expatriates relied on 'rules of thumb' supplied by tax advisors to classify themselves as non-residents for tax purposes. A recent ATO ruling is intended to provide clearer guidelines concerning the residency rules under the current income tax law for all types of individuals entering Australia. This may have led to more foreign expatriates, such as executives, becoming residents for tax purposes. As many employers agree to pay tax on expatriates' behalf, the ruling may result in higher costs to businesses wishing to employ expatriates.

On taking up residence in Australia executives and other key personnel are likely to own overseas investments and housing that will produce income that will become taxable in Australia even if the executives are here for less than four years. Taxing the income from these pre-residence investments at Australia's top rate of personal tax could increase the overall tax burden and deter the executives from taking up opportunities in Australia.

The recommendation will help address these current deterrents to locating in Australia. Modifying the tax consequences of relocating key staff to Australia as proposed could facilitate Australia's growth as a financial centre. The proposal in Recommendation 22.17 to subject non-residents' wage and salary income to the company rate of tax should also encourage non-residents to take up temporary opportunities in Australia.

Recommendation 22.19 - Residents departing Australia - employee share schemes

| Restoration of employee share discounts to taxable income

Employee shares derived from service in more than one country

|

Under current law, tax on a discount given to an employee in relation to 'qualifying' shares or rights acquired under an employee share scheme may be deferred for up to 10 years unless a 'cessation time' event occurs (for example a right is exercised, or a share is sold, or the employee ceases to be employed by the employer providing the scheme). Ceasing to be an Australian resident for tax purposes is not currently considered a 'cessation time' event. If the shares or rights were granted while the employee was a resident it is appropriate to trigger tax when the employee ceases to be a resident to facilitate collection of the tax.

More complicated issues arise where shares or rights relate to service in more than one country whether the employee is a resident or a non-resident. The development of appropriate rules may require bilateral agreement with other revenue authorities within the framework of our DTAs, following consultation with business.

Recommendation 22.20 - Residents departing Australia - security for deferred capital gains liability

| That to provide some assurance that deferred capital gains tax is eventually paid when relevant assets are disposed of, a resident who elects to defer capital gains tax when ceasing to be an Australian resident be required to give appropriate security to the Australian Taxation Office. |

As a general rule taxpayers are liable for capital gains tax on accrued but unrealised gains on certain assets that they hold at the time they cease to be a resident. However, a taxpayer who ceases to be a resident may elect to defer payment of their capital gains tax liability until disposal of the asset.

There is currently a risk that provisions for the deferral of capital gains tax and deferral of tax in relation to benefits under employee share schemes could be used by foreign expatriates and other taxpayers ceasing to be residents to avoid Australian tax obligations.

Canada has recently released (December 1998) legislative proposals in relation to taxpayer migration which are designed to enhance Canada's ability to effectively tax emigrants' Canadian source gains. A feature of the proposals is that emigrants that do not pay tax on the gains prior to their departure are required to provide appropriate security to Revenue Canada. The Review considers that this approach should be adopted in Australia.

Improving Australia's Double Taxation Agreements

Recommendation 22.21 - Lower rates of DWT on non-portfolio investment

| That in negotiating Double Taxation Agreements, Australia endeavour to reduce dividend withholding tax rates on non-portfolio investment. |

Several submissions stressed the importance of DTA issues, particularly seeking a reduction in foreign DWT rates. The Review shares that view, but also notes that since DTAs are bilateral agreements it is necessary to gain the agreement of other countries to commence negotiations and to reach an outcome that provides net benefits to both countries.

Globalisation has provided opportunities for Australian companies to expand offshore for their own and Australia's overall benefit. The interaction of this trend and the imputation system has led the Review to recommend an imputation credit for foreign dividend withholding taxes up to a 15 per cent tax rate (Recommendation 20.1). For many entities, however, foreign dividend withholding tax represents an additional tax burden which the imputation measure may not overcome (for example, if the entity already has undistributed imputation credits). Hence a complementary measure would be to negotiate to reduce the foreign DWT - benefiting Australia since more income is returned here and subject to Australian tax.

The international norm for dividends is to have lower DWT rates for non-portfolio investment (typically 5 per cent in most bilateral tax treaties, but with significant cases of zero rates as for example in the European Union). The definition of non-portfolio investment varies, but is often defined as a holding of either 10 per cent and greater of voting power, or 25 per cent and greater of capital. The motivation for reducing DWT rates is to facilitate cross border direct investment by lowering the tax cost of repatriation of profits (dividends) at the border. A positive rate such as 5 per cent retains some source country taxation of those profits in the hands of shareholders. Australia, reflecting its position as a net capital importer, traditionally sought in its DTAs a DWT rate of 15 per cent on both non-portfolio and portfolio dividends. When the imputation system was introduced in 1987, Australia unilaterally reduced its DWT on franked dividends paid to non-residents to nil. Unfranked dividends continued to be taxed generally at a 15 per cent DWT rate. However, Australia's DTAs continued to allow its treaty partners to levy DWT on non-portfolio and portfolio investors' dividends at 15 per cent - hence Australian investors received no complementary benefit (although some countries, for example the UK, have unilaterally removed DWT).

Since 1994 Australia has sought lower foreign DWT rates on non-portfolio dividends on the basis of lower Australian DWT rates on certain franked dividends. Australia has used the franked/unfranked distinction on its side while the portfolio/non-portfolio distinction has been used by the other country.

The Review commends the direction of the recent policy change and recommends that Australia should press strenuously to have foreign tax on dividends on non-portfolio investment reduced in future Treaties.

This would significantly benefit Australian investment offshore, particularly into the US which currently levies DWT at 15 per cent in the (now aged) DTA with this country, but not in many of its other DTAs. This recommendation has received strong support in submissions and consultations.

If the foreign country agrees to a reduced DWT rate there will be a comparable reduction in the imputation credit to the DWT that is agreed.

In the DTA negotiation process consideration should also be given to providing imputation credits for branch profits taxes imposed on the repatriation of those profits to Australia.

Recommendation 22.22 - Inclusion of a non-discrimination article

| That Australia agree to a non-discrimination article (NDA) in future DTAs in accordance with international norms. |

A non-discrimination article in a DTA requires, broadly, that a non-resident investor be treated no less favourably than a comparable resident investor in a comparable situation. Australia is the only OECD country which does not include a non-discrimination article in its DTAs. Traditionally this position was regarded as necessary to protect Australia's source country taxing rights and our narrow tax base prior to 1985. However, a recent international study found that Australia's tax rules constitute one of the least discriminatory tax regimes applying to non-residents.

Australia should be prepared to bind itself in DTAs not to discriminate in relation to taxation - particularly given its good record in this area. Further, as Australian enterprises expand overseas, they would be able to rely on reciprocal rules to protect them against tax discrimination in foreign countries. Australia's current position on NDAs has also meant that progress in renegotiating Australia's major tax treaties has been difficult; a change of policy will greatly assist in implementing the next recommendation.

Inserting an NDA in our future DTAs may require Australia to extend a small number of tax measures to non-resident investors. For example, it may be necessary to extend R&D concessions to branches. However, Australia in common with many other countries would continue to preserve measures such as thin capitalisation provisions that ensure that non-residents pay their fair share of Australian tax.

Recommendation 22.23 - Priority for DTAs with major trading partners

| That priority be given to renegotiating aging DTAs with major trading partners to make them consistent with Australia's current DTA policy and with decisions concerning tax reform. |

Australia's DTAs with the UK and Japan date to 1967 and 1969 respectively. Although the current US Convention dates from 1983, essentially it reflects a bargain struck in the early 1970s. None of these DTAs properly reflects modern tax treaty policy, and of course cannot reflect decisions yet to be taken concerning business tax reform. Neither do they take into account emerging tax treaty issues such as arbitration, assistance in recovery, data protection and offshore activities. Since Australia has major economic links with these countries, priority should be given to renegotiating these DTAs after the business tax reform measures are implemented.

Recommendation 22.24 - Review of DTA policy

| That to assist Australia's competitiveness, Australia's overall DTA policy be reviewed in order to ensure that it reflects a balanced taxation of international investment and changed investment patterns. |

Current DTA policy places greater emphasis on source country taxing rights than does the OECD Model Convention. This reflects that Australia has traditionally been a net capital importer. For example, in the first half of the 1980s, Australian investment abroad was only 10 to 20 per cent of the volume of foreign investment in Australia. Currently, Australian investment abroad is about 60 per cent of the level of foreign investment in Australia (see A Strong Foundation, Figure 2.3).

This suggests the need for a review of DTA policy to ensure that our DTAs reflect an appropriate balance of source and residence based taxing rights that will encourage both inbound and outbound investment.

Changes to entity taxation in particular as a result of tax reform will give rise to a number of DTA issues. The reforms proposed by the Review have been designed generally to fit with current DTAs given that it will take many years to renegotiate all of Australia's current DTAs. In some cases (such as the international treatment of trusts), greater certainty and more appropriate results will be achieved by seeking changes to current DTAs as they are progressively renegotiated.