Review of Business Taxation

A Tax System RedesignedMore certain, equitable and durable

Report July 1999

SECTION 5 - SOME SPECIFIC ISSUES IN TAXING INCOME

| A new approach to taxing fringe benefits |

| Clarifying the mutuality exception |

| Principles for taxing government grants and subsidies |

| A no-detriment approach to involuntary receipts |

A new approach to taxing fringe benefits

Recommendation 5.1 - Transfer of tax liability for fringe benefits to employees

|

Fringe benefits to count as employee income

|

|

Date of effect

|

The taxation of fringe benefits on the employer (rather than the employee) at the top marginal rate for individual taxpayers is seen by business as complex, administratively burdensome and discriminatory against both employees on less than the top rate, as well as expatriate employees. As a result, the Review recommends a major overhaul of the taxation of fringe benefits that delivers a more equitable and efficient outcome, while maintaining revenue from the taxing of benefits.

The key tax reform option for fringe benefits put forward for consideration in A Platform for Consultation (page 774) was to dispense with fringe benefits taxation (FBT) and attribute the taxable value of fringe benefits (with the exception of entertainment and on-premises car parking) to the relevant employee. The widespread support (albeit not unanimous) from all sectors of business for this option during the consultation process has reinforced the Review's position on this issue.

Counting fringe benefits as employee income would be in line with the changes announced in A New Tax System, which have resulted in fringe benefits being taken into account in income tests used to assess a taxpayer's liability for various payments and levies and access to certain benefits. It would also be consistent with other changes recommended by the Review which will ensure that all fringe benefits provided to members of entities, in their capacity as members, will be a personal income tax liability rather than an FBT liability for the entity.

Taxing in the hands of the employee will make fringe benefits subject to the same tax rates as other components of employee remuneration and the same administrative arrangements. This will deliver administrative efficiencies for employers and the Australian Taxation Office (ATO). It will also improve equity (because employees would be taxed at their marginal tax rates) and address a long-held concern of business that employers should not be legally liable for a tax that relates to the income of employees.

In addition, taxing in the hands of employees will overcome a form of double taxation faced by expatriates working in Australia for foreign firms. Taxation authorities in a number of countries include the receipt of fringe benefits in their assessment of expatriates' income taxation liability, yet do not provide a credit for the FBT built into expatriates' salary packages because Australian FBT is currently a tax on employers. It is also not feasible to relieve, through the Australian tax treaties with other nations, the double taxation that arises from the two different bases of taxation. These treaties would, however, address this problem if the benefits were based on income of the employee.

Implementation issues

For business, implementing this recommendation will represent only a small addition to the administrative requirements for fringe benefit reporting announced in A New Tax System. For the financial year ending 30 June 2000, business will already have been required to report fringe benefits on employees' group certificates when the value of benefits is in excess of $1,000.

Under the Review's recommendation there will be a somewhat greater level of reporting on group certificates because the $1,000 de minimis level will not apply. But this should not be a major issue since records of all benefits have to be kept in many cases to ensure the de minimis level is not exceeded. Further, as now, employers will not have to record employee fringe benefits of a trivial or 'minor' nature on group certificates because the current provisions that exempt 'minor benefits' will remain in place. For example, a Christmas gift to an employee up to a value of $100, safety awards up to $200 and taxi travel provided after an employee has worked overtime will all continue to be exempt from tax and therefore not reportable on group certificates.

It has been suggested that implementing this recommendation will increase compliance costs unnecessarily since, for the same level of tax receipts, the tax collection task in effect would switch from a relatively small number of taxpayers (employers) to a much larger group (all employees in receipt of fringe benefits). This is based on a misconception. It is important to appreciate the difference between the effect of a transfer in tax liability and the method of tax collection.

It is correct that this change to fringe benefits taxation will result in a transfer of legal liability from employers to all employees in receipt of fringe benefits. The tax collection task, however, will remain with the employer who would simply remit tax on employee fringe benefits via the PAYG system instead of the separate FBT system. This will reduce the administrative burden. Employers will calculate the value of benefits, as now, and report these on employees' group certificates (which will apply in any case from the financial year commencing 1 July 1999).

Thus, in practice there would be little expansion of compliance load for most employers. For many, there would be a reduction, as a result of the removal of separate FBT systems. There would be no extra compliance costs for employees. The measure will therefore essentially only change the name of the tax remitted by the employers. It would not result in any increase in the number of persons remitting tax.

Revenue implications

Implementing this recommendation alone would reduce taxation revenue because all benefits would become taxable at the employee's marginal rate, which, especially with the new personal marginal rate scale, for many employees will become lower than the 48.5 per cent FBT rate. However, there are strong grounds to believe that, ahead of this change, employees on less than the top marginal tax rate will already have sought to have their fringe benefits effectively taxed as income at their marginal rate through the use of employee contributions. (The taxable value of fringe benefits can be reduced by the amount of any offsetting payment made by an employee from their after-tax income to the employer. The ATO is advising taxpayers of this mechanism in information provided on the reportable fringe benefits requirements applying under A New Tax System.)

Transition process

Employment contracts will need to be renegotiated in some instances as a result of transferring tax liability to employees. In order to facilitate a smooth transition, there would be merit in giving employees and employers two years prior notice of the change. This time period will also allow both employers and employees to establish and settle down the fringe benefits reporting requirements instituted by A New Tax System before having to deal with this additional change.

Recommendation 5.2 - Business entertainment expenses

|

Non-deductibility of business entertainment expenses

|

|

Definition of business entertainment expenses

|

|

Entertainment allowances

to be employee income

|

|

Treatment of exempt bodies

|

Two exceptions will need to be made - having significant compliance benefits - to the general recommended approach of taxing fringe benefits in the hands of the employee. The first refers to the treatment of employee costs associated with entertaining business clients.

The compliance costs associated with the fringe benefits treatment of entertainment are widely recognised as onerous and the consultation process evinced strong support from all quarters for simplifying current arrangements further. Attributing a share of entertainment costs to individual employees would only exacerbate compliance costs - as is already recognised in the design of the reporting requirements in A New Tax System. Under these requirements, entertainment by way of food and drink or hire and lease of entertainment facilities is excluded from the group certificate reporting measure because of the high compliance costs involved.

A much simpler alternative - Recommendations 5.2(a) and (b) - is to remove business entertainment fringe benefits from fringe benefits coverage and to treat client and employee entertainment expenses in a consistent manner by making both non-deductible business expenses for employers. In essence, the Review recommends a return to the treatment of entertainment that applied before 1995. But a need has been identified to be more prescriptive in guarding against exploitation of concessional treatment of private entertainment (effective taxation at the employer's rate rather than the employee's) to minimise the effects on government revenue.

The approach recommended by the Review is a compromise which allows employers to deal in a consistent manner with the entire costs of a wide range of business related events. For example, if business is conducted with clients in a restaurant, the boardroom or in a corporate box, or as part of a catered promotional launch in a marquee, none of the meal and other entertainment costs will be regarded as fringe benefits. As an offset, no deduction will be allowed to the employer against income tax for any of the costs.

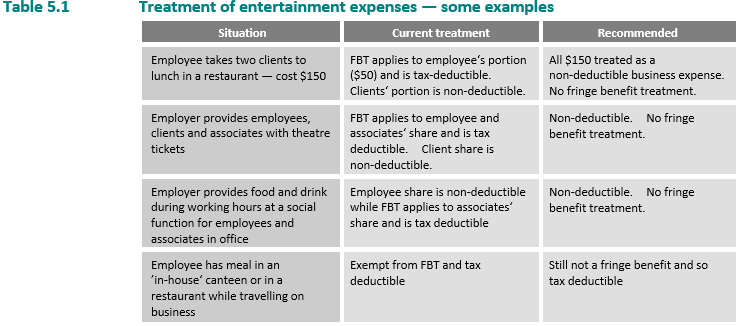

This approach removes any need for employers to keep records of attendance at functions and to separate the different cost components. This will significantly reduce compliance costs for business and simplify the administration of the taxation system. Examples of the current and recommended treatment of entertainment expenses for taxable entities are set out in Table 5.1 below.

Recommendation 5.2(b)(ii) will give rise to a list of private functions to be excluded from being non-taxable fringe benefits. Such a list will make it easier for business and the ATO to identify the boundary between business-related entertainment and entertainment that is essentially of a private nature.

Under Recommendation 5.2(c), entertainment allowances provided ahead of any expenditure to employees will be taxed like other forms of income of the employee. This will guard against employees switching salary into an entertainment allowance in order to benefit from any difference between their marginal tax rate and the loss of deductibility of entertainment expenses to the employer. Having employees seek reimbursement or requiring the employer to pay direct will create a more traceable record of business-related entertainment expenses than would occur with the use of entertainment allowances.

For this measure it is necessary to apply a one year implementation delay compared to the Review's other fringe benefit recommendations in order to avoid a transitory higher revenue cost in the first year. The higher cost arises because of the combined effect of an immediate removal of FBT on employees business entertainment expenses and a lagged adjustment in company income tax instalments from the removal of deductibility on fringe benefit entertainment.

Tax-exempt bodies

Currently FBT applies to remuneration in the form of entertainment provided to employees of tax-exempt bodies. This treatment was designed prior to 1995 to achieve some comparability in the treatment of entertainment between exempt and taxable entities. Prior to 1995, tax on remuneration by taxable employers in the form of entertainment was achieved through non-deductibility. Income tax exempt employers, like State Government departments and instrumentalities, could not be taxed by that means because tax deductions had no relevance to their financial outcomes and so the FBT was applied to entertainment benefits provided to their employees.

Recommendation 5.2(d) has been included because the Review has judged that it would be too administratively difficult and inequitable to treat business-related entertainment undertaken by employees of exempt bodies in the same manner as is recommended for other fringe benefits - that is, to allocate to the individual employee and count as employee income. Alternatively, the cost and complexity in retaining a vestigial FBT would outweigh the $20 million of tax revenue currently generated from this source.

Recommendation 5.3 - On-premises car parking

| That car parking provided 'on-premises' or in associated buildings covered under leasing or rental arrangements be removed from fringe benefits coverage as from, and including, the 2001-02 income year. |

The second exception to the general recommended approach of taxing fringe benefits in the hands of the employee relates to 'on-premises' car parking.

Like entertainment, it is already recognised that car parking fringe benefits (other than car parking expense payments) cannot be easily attributed to employees. These fringe benefits are excluded from the group certificate reporting requirements announced in A New Tax System.

Under the current FBT regime, small business is already exempt from 'on-premises' car parking and non-CBD parking is largely exempted because of a de minimis value rule. So exempting all 'on premises' car parking will make the treatment of this expense consistent across all forms of business as well as reducing compliance costs.

An issue raised in the consultation process is that in many CBD areas, car parking is not provided strictly 'on-premises'. Because of building leasing arrangements, the Review recognises the exemption should apply to car parking provided in associated buildings covered under leasing/rental arrangements.

Recommendation 5.4 - Valuation of car benefit

|

Schedular approach to replace statutory formula

|

|

Application only to new car leasing arrangements

|

Determining the taxable value of car benefits from the statutory formula provides significant concessionality for a large proportion of car fringe benefit cases. A more rational statutory valuation will serve the dual purposes of eliminating some anomalies in the impact of the current formula and of balancing the overall revenue impact of the Review's fringe benefit recommendations in the short to medium term.

Because the taxable value of the benefit under the current formula actually falls by substantial steps as total kilometres rise, there can be a significant incentive to travel unnecessary kilometres toward the end of the fringe benefits year. In consultations, mention was made of the 'March Corporate Rally', a term used to describe the excessive car travel that takes place around the end of March each year. The proposed schedular approach establishes a more rational approach because it provides a closer tracking of actual costs.

The Review's recommended approach for valuing car benefits will be almost as simple as using the current formula and should not present computational difficulty for employers.

To allow time for employers and employees to renegotiate remuneration arrangements, where needed, the change in the valuing of car benefits will be phased in as current car leasing arrangements expire.

Impact on car sales

At the recommended 45 per cent level of presumed business use, car fringe benefits will still attract a sufficient degree of concessionality to remain an attractive form of remuneration for most employees. The domestic car industry has argued that any tightening of the formula would damage its sales and encourage employees to choose cheaper, imported, cars. The Review is not convinced that the car industry will suffer as badly as it suggests. Price relativity appears not to be the major consideration at present. And to the extent that relative costs do influence the choice of car, the proposed scale will in fact erode the cost advantage of some low-priced imported cars.

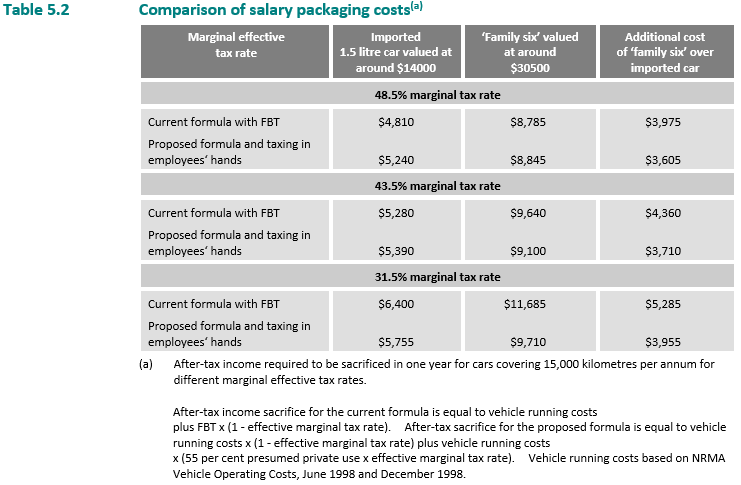

To illustrate both these points, NRMA business running cost figures indicate that an employee on the top marginal rate with a fringe benefit car presently must give up after-tax income of about $8,785 per annum for a locally produced six cylinder car doing 15,000 kilometres, while the amount for a popular imported model is $4,810. So the imported model would appear to be 45 per cent, or $3,975, cheaper than the larger local. Despite this large relative and absolute cost disadvantage, local medium/large cars still dominate the business fleet market.

The proposed statutory formula will narrow both the percentage and absolute gap between the local and imported cars in this example (see Table 5.2). For those on the top marginal tax rate, the local car will require an after-tax salary sacrifice of $8,845 while the sacrifice needed for the imported car will be $5,240. The 45 per cent advantage of the imported car will have been marginally reduced to 41 per cent and the price gap falls by $370.

For those on less than the top marginal tax rate, the price gap will fall even further. This is because the effect of a switching to taxing benefits in employees' hands offsets the reduction in the concessional treatment of car benefits. At the 31.5 per cent marginal income tax rate, for example, the gap between the imported and the larger locally produced car will decline by $1,330 in favour of the locally produced car.

The overall impact on the local vehicle market is difficult to estimate because of offsetting influences. The position of local producers will be improved relative to imports. But there is a general reduction in the attractiveness of fringe benefit arrangements for most cars covering more than 15,000 kilometres. However, this is offset for some taxpayers by the fall in the tax rate from 48.5 per cent to their personal marginal tax rate.

Recommendation 5.5 - Direct subsidies for FBT-exempt and rebatable employers

| That the exemption and rebate of FBT available to certain employers be discontinued and the benefit replaced with a direct subsidy payment. |

As raised in A Platform for Consultation (page 776), dispensing with FBT and transferring tax liability to relevant employees would, in itself, eliminate the benefit enjoyed by exempt and rebatable employers from paying employees in the form of fringe benefits. A different approach is required for these organisations if they are to be compensated for the loss of the benefit.

This benefit is to be capped under the proposals in A New Tax System. Exempt employers such as charities and some public hospitals are to be able to provide up to $17,000 grossed-up value of fringe benefits to an employee without incurring an FBT liability. Rebatable employers - which include certain other hospitals, trade unions, employers' organisations and community and sporting clubs - are to be allowed a continuation of their rebate (48 per cent of FBT payable) in respect of up to $17,000 grossed-up value of fringe benefits. These arrangements are not appropriate if FBT is eliminated.

With abolition of the FBT system under the Review's recommendation, the Government may wish to continue delivering the capped level of assistance through a taxation concession for employee fringe benefits. The capped level of assistance could be replicated by allowing an exemption/deduction of up to $8,000 to employees of FBT-exempt organisations in respect of reported fringe benefit income. An exemption/deduction of 48 per cent of fringe benefit income, up to a maximum of $8,000 of reported fringe benefit income, would replicate the assistance for employees of rebatable employers.

The amount of $8,000 would closely mirror the underlying taxable FBT value of $17,000 worth of 'grossed-up' benefits under present arrangements. As the 'gross-up' factor applicable under A New Tax System is approximately 2.13, the underlying taxable value of the benefit limit becomes $17,000/2.13 = $7,980. Under a regime of taxing benefits in the hands of employees, the concept of grossing up has no logical place. The limit on the benefit needs to be defined in terms of the underlying taxable value - which would be the value to appear on all employees' group certificates.

However, the Review is concerned that in a very short time, it can be expected that virtually all employees of tax-exempt bodies would be remunerated to the full value of this concession (regardless of whether it is provided under current FBT arrangements or under the Review's recommended abolition of FBT).

The Review understands that under the arrangements prior to A New Tax System many tax-exempt bodies were not using the available concession to the extent of the proposed limit. Now that it has been validated it will be clearly in their interests to reduce their employment costs by utilising the concession fully. The Review is not convinced that the proposal announced in A New Tax System will be sustainable in the longer term because of the eventual cost to revenue.

Where the tax-exempt body is engaged in business activity, this tax break could provide them with a competitive edge over ordinary businesses.

The Review considers that this element of government assistance to charities and the like should be removed from the tax system and replaced by a direct identifiable subsidy, which maintains a similar level of support. A subsidy will be more transparent and deliver a better match between the intentions of government and the outcome. Addressing this issue now before it becomes a more intractable and expensive problem later has much to commend it.

Other issues

Alignment of tax years

The Review received mixed views from business on the extent to which alignment would simplify compliance. Submissions varied between retention of the present system, full alignment or allowing the taxpayer to choose either approach. This would be a relevant issue even in the event that the Review's recommendations for abolishing FBT were not implemented.

The Review has concluded that a judgment on where the balance of all the arguments lies cannot be made while business is preoccupied with implementing the reportable fringe benefits requirements instituted by A New Tax System - in particular, the assignment and inclusion on group certificates of employee fringe benefits from the financial year commencing 1 July 1999. Implementation of effective information systems for that requirement might ease complications associated with aligning the tax years.

Accordingly, the Review suggests that government should revisit the issue once A New Tax System requirements (and any others that flow from this Report) have been settled down.

Specific exclusions approach

Finally, in similar vein, the Review noted that in the consultation process there was not widespread support for replacing the current approach, whereby FBT applies to all fringe benefits unless they are specifically excluded, with a system of specific inclusions.

The Review has not been persuaded that a specific inclusion approach has clear advantages. Moreover, in relation to the changes recommended for the treatment of entertainment fringe benefits, it has been necessary for revenue protection reasons to continue largely to rely on an exclusion approach.

Clarifying the mutuality exception

Recommendation 5.6 - Mutuality principle

|

Statutory exclusion for 'mutual gains'

|

|

Apportioning expenditure between member and non-member income

|

All transactions between members and entities will be treated consistently according to the same general rules under the taxation principles recommended elsewhere by the Review. Without specific exclusions, this would result in gains that are presently exempt because of the 'mutuality exception' being included in the calculation of taxable income.

The 'mutuality exception' is a longstanding common law rule (not an explicit provision in the current tax law) having the effect that identified gains of some organisations from some dealings with their members - 'mutual gains' - are not income for the purposes of the present income tax law.

Under the common law exception, where a number of persons contribute to a common fund created and controlled by them for a common purpose, any surplus arising in the fund is not income for tax purposes. This rule applies to bodies such as clubs, friendly societies and their dispensaries. The present law contains some rules for taxing certain member income of some of the subsidiaries of these bodies. But beyond that, some gains of these bodies from dealing with members remain free of tax.

There is, however, an anomaly in the interaction between the common law rule and the operation of the present law in relation to the allowance of deductions. Absent an appropriate rule, the present law (which was never designed to deal with the significant commercial activities undertaken under mutual principles) effectively allows a disproportionate share of deductions against assessable income, thus minimising taxable income.

To maintain the current tax status of mutual gains of entities will require a balancing adjustment to be made at the end of each income year equal to the entity's mutual gains for the year. Entities will need to examine their transactions (as they do now) so as to distinguish those that are mutual transactions with members from non-mutual dealings. This effectively replicates the current tax treatment. The adjustment for mutual gains of entities will be expressly stated in the tax legislation.

A corresponding balancing adjustment for mutual losses is also required. This will allow equitable apportionment of expenditures and liabilities as well as receipts and assets in applying the mutual exception.

Special exceptions will not be needed in the case of many entities which have already been expressly excluded from the mutuality exception in the tax law. These include insurers, co-operatives and effectively all financial institutions.

Principles for taxing government grants and subsidies

Recommendation 5.7 - Grants and subsidies paid by the Commonwealth Government

| That where grants or subsidies are provided by the Commonwealth Government, enabling Commonwealth legislation make explicit that one of the following treatments will apply: |

|

Permanent tax-free (non-taxable/deductible) treatment

|

|

Tax-deferred (non-taxable/non-deductible) treatment

|

|

Immediately taxed (taxable/deductible) treatment

|

Current treatment

In A Platform for Consultation (page 87), the Review discussed whether the cost base of an asset should be reduced by subsidies received.

Government grants or subsidies paid to businesses are generally taxable in the year they are received. This has been a long-standing feature of the tax law. It is based on the principle that a subsidy or grant increases the net wealth of a taxpayer and hence ought to be taxable. The existing law provides symmetrical treatment in that a subsidy or grant is taxable and associated expenditures are deductible. Thus if the subsidy or grant were applied to:

- •

- acquiring a depreciable asset - the expenditure would be deductible at the applicable rate of depreciation;

- •

- paying wages - the expenditure would be deductible as incurred; and

- •

- the acquisition of an appreciating asset, such as land - there would be no deduction, but the cost base would not be adjusted by the amount of the grant or subsidy.

The existing law for the treatment of taxable grants and subsidies can result, however, in inequitable outcomes. For example, where a grant is made to enable a particular asset to be acquired such that there is no change in the taxpayer's net cash position, the acquirer may not be in a position to meet the tax liability. Also, providing grants that are taxable up front will have different taxation consequences, depending on the tax positions of the recipients at the time the grant is made.

Alternative treatments

The Review believes that, where the Commonwealth Government provides grants and subsidies, the intended tax treatment should be made explicit by the Commonwealth Government and that the treatment have regard to the nature and purpose of the subsidy or grant.

Under the recommended approach the taxation of grants and subsidies would fall into three categories.

- (i)

- Under the permanent tax-free (non-taxable/deductible) treatment, grants and subsidies would be exempt from tax and the associated expenditure would be fully deductible in accordance with the normal operation of the law. Under this category, the grant or subsidy would be accorded the same treatment as a gift.

- (ii)

- Under the tax deferred (non-taxable/non-deductible) treatment, grants and subsidies would be non-taxable and the associated expenditures would not be deductible. Where a grant or subsidy is to assist a business to carry on normal day-to-day activities - for example, to employ additional labour or to meet other recurrent costs - the recurrent expenditure would not be an allowable deduction (though the taxable/deductible approach would be easier to apply and there would be a matching of the income and expenditure within a relatively short period of time). Where a grant or subsidy is made to acquire an asset - land or an item of equipment, for example - the tax value of the asset would be reduced (with higher tax then payable over time).

- (iii)

- Under the immediately taxed (taxable/deductible) treatment, the grant or subsidy would be fully taxable in the year it is received and the associated expenditures would be deductible in accordance with the normal operation of the law.

In principle, the Commonwealth Government would be indifferent between each of these approaches with respect to grants or subsidies made by it if the amount of the subsidy or grant were determined on the basis of the after-tax benefits to the recipient.

Grants and subsidies made by State, Territory and Local governments

State, Territory and Local governments are not empowered to designate the taxation treatment of grants or subsidies made by them. Under the taxation law, grants or subsidies made by them would be taxed as normal income unless specific provisions were enacted by the Commonwealth.

The States and Territories would, as in the past, have to raise the implications of the tax treatment of particular State or Territory grants with the Commonwealth on a case-by-case basis.

A no-detriment approach to involuntary receipts

Recommendation 5.8 - Guiding principle for taxing involuntary receipts

| That involuntary receipts be taxed according to the principle that taxpayers be neither better nor worse off in after-tax terms than they would have been had the involuntary event not occurred. |

The current taxation rules for involuntary receipts do not result in consistent treatment of involuntary receipts based on a common set of principles. Submissions and focus group participants agreed that the taxation of involuntary receipts was in need of reform.

Equity considerations

As noted in A Platform for Consultation (page 319), there are equity and cash flow arguments for treating involuntary disposals differently from voluntary disposals ? because, in the absence of special treatment, a tax liability may be triggered through no choice of the taxpayer. Such a tax liability may create cash flow problems for a taxpayer seeking to replace the asset subject to the involuntary disposal. Submissions and the participants in the focus group agreed that there was a case for taxing involuntary receipts differently from other income.

Coverage

The recommendations are intended to apply to all asset types except trading stock.

Trading stock is intentionally not covered by the above approach because it is generally held for relatively short periods before sale with the intention of realisation. This obviates any need to treat involuntary disposals of trading stock differently from voluntary disposals.

Recommendation 5.9 - Defining involuntary

|

|

There are strong practical and commonsense arguments for defining as involuntary negotiated disposals where the statutory power to acquire is held in reserve. If negotiated sales under threat of compulsion were not treated as involuntary, taxpayers would simply not negotiate and the acquirer would be forced to exercise its compulsory power (A Platform for Consultation, page 320). Such an approach would be wasteful and inefficient.

Allowing compulsory acquisitions of minority interests under the Corporations Law to be accorded the involuntary receipts treatment would create an incentive for taxpayers formally to reject takeover offers in the expectation of receiving more favourable treatment than that available to taxpayers who accept offers. This would impede the efficient functioning of the market and would be unfair to those taxpayers who accept the takeover offer. Consequently involuntary receipts treatment will not apply in relation to takeover offers for securities.

Recommendation 5.10 - Treatment for involuntary realisations

|

Reduction of tax value of replacement asset

|

|

Quarantining

|

|

Taxation of excess

|

Allowing the taxpayer to roll over any gain on an asset to a replacement asset or assets is consistent with the overarching principle of the taxpayer being neither better nor worse off in after-tax terms following the involuntary event. Submissions and the participants in the focus group agreed that the taxpayer should be able to defer the gain to a replacement asset or assets.

For taxpayers subject to the capital gains treatment, quarantining of the rolling over of gains arising from an involuntary realisation of a non-capital gains treatment asset to a non-capital gains treatment replacement asset is justified because taxpayers could be made better off by the involuntary event if quarantining did not apply. Without quarantining, taxpayers could halve the gain arising from an involuntary realisation of a non-capital gains treatment asset by rolling it over to an asset subject to capital gains treatment.

Where the gain exceeds the tax value of the replacement asset or assets, it is appropriate to tax the excess at the end of the replacement asset period because the taxpayer has voluntarily decided to purchase a replacement asset or assets with a tax value less than the gain involuntarily realised. The taxpayer has, in effect, 'voluntarily' realised part of the original asset.

Recommendation 5.11 - Transfer of pre-CGT status

| That the pre-CGT status of an asset involuntarily disposed of be preserved by transferring that status to a replacement asset or assets. |

The maintenance of pre-CGT status of a compulsorily acquired asset is also consistent with the overarching principle of the taxpayer being neither better nor worse off following the involuntary event.

The Review notes that with the existing CGT rollover for certain involuntary disposals, the requirements for preserving pre-CGT status for a replacement asset differ depending on whether or not the involuntary disposal occurs because of a natural disaster.

In a non-natural disaster case, the taxpayer retains pre-CGT status only if the expenditure to acquire a replacement asset is no more than 120 per cent of the original asset's market value. In a natural disaster case there is a more flexible test, which preserves pre-CGT status where it is reasonable to treat the replacement asset as substantially the same as the original asset.

The Review considers that the present distinction is inappropriate because it leads to differential treatment of taxpayers in substantially the same economic circumstances. It therefore supports the use of the more flexible test in all cases of involuntary receipts.

Recommendation 5.12 - Treatment when no realisation

|

Tax value reduction

|

|

Excess tagged to asset

|

|

Pre-CGT assets

|

Where there has been damage to, or loss of value of, an asset or where there has been a compulsory creation of a right over an underlying asset, the reduction in the tax value of the relevant asset by the amount of compensation leaves the taxpayer neither better nor worse off.

If the amount of compensation is greater than the tax value of the underlying asset, the excess ought to be eventually subject to tax or the involuntary event would make the taxpayer better off. By deferring the taxing event until the asset is actually disposed of, the taxpayer is treated as though the involuntary event had not occurred.

Under the existing law a compulsory right taken over an underlying pre-CGT asset is not taxable and the Review proposes that this treatment be maintained.